Welcome to Week Nine of our Wuthering Heights read-along…

This week’s assignment is Volume 2: Chapters XVIII-XX

What Happens in Chapters XVIII-XX?

It is now 1802, one year has passed since the death of Edgar Linton. Again, it is Harvest time. And, our read-along has come to its conclusion.

I‘d like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to everyone who encouraged me to pursue a read-along of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. Whether you were reading the novel for the first time, or re-visiting the story, I sincerely hope that my weekly summaries offered you additional insight into the story and inspired you to think critically about the characters and the narrative. I’ve learned a lot about hosting a read-along; I plan to offer a different kind of Wuthering Heights read-along in the fall—details to come!

Now, let’s discuss how The Story of Heathcliff concludes…

‘All’s shut up at Thrushcross Grange’

Just as the first three chapters of Wuthering Heights began, the first of the last three chapters includes a timestamp—1802. And again, we find ourselves under a Harvest Moon.

Mr. Lockwood, whose Christian name we’ve never learned, again narrates. He tells us he has returned to the neighborhood, invited, ‘to devastate the moors,’ by a friend—in other words, to hunt game birds. When he learns he is within traveling distance to the Grange he decides to visit, stay the night, and settle his bill with Heathcliff.

The grey church looked greyer, and the lonely churchyard lonelier. I distinguished a moor sheep cropping the short turf on the graves. It was sweet, warm weather—too warm for traveling; but the heat did not hinder me from enjoying the delightful scenery above and below; had I seen it nearer August, I’m sure it would have tempted me to waste a month among its solitudes. In winter, nothing more dreary, in summer, nothing more divine, than those glens shut in by hills, and those bluff, bold swells of heath.

When Lockwood arrives at the Grange he discovers ‘an old woman reclined on the horse-steps, smoking a meditative pipe,’ along with a child (aged nine or ten). They reside at the Grange; it seems Ellen Dean has moved to the Heights.

Horse-steps (what are now called mounting blocks), were used to mount and dismount a horse. And while it may seem surprising, women in the 1700s often smoked pipes; it was a practice generally embraced only by the lower classes.

Lockwood—allowing the old woman to prepare him a corner in which to sup and a place to sleep for the night—travels to the Heights, planning to pay his rent through the end of the season, so he needn’t return. Once there, he is surprised to find quite the opposite situation from what he described for us in Chapter One of the novel.

Let’s compare…

from Chapter One

Even the gate over which [Heathcliff] leant manifested no sympathizing movement to the words (“Walk in!”)…when he saw my horse’s breast fairly pushing the barrier, [Heathcliff] did pull out his hand to unchain it…

and now, Chapter Eighteen (Thirty-two)

I had neither to climb the gate, nor to knock—it yielded to my hand.

A welcoming entrance combined with, ‘a fragrance of stocks and wall flowers,’ wafting on the air and, ‘both doors and lattices open,’ Lockwood is perplexed!

His surprise is soon replaced, ‘by a mingled sense of curiosity and envy.’ Gazing through an open window, he discovers Cathy and Hareton. Hareton is reading aloud and if his pronunciation proves successful, the young man’s reward (to the envy of Lockwood) is an abundance of kisses received from his eager cousin.

Upon finding Nelly in the kitchen, Lockwood learns Zillah left the Heights soon after Lockwood departed for London. And when he informs her he’d like to pay his rent, he is informed he must settle with Cathy, (but for now) Ellen Dean; Cathy, ‘has not learnt to manage her affairs yet.’

And Nelly furnishes Lockwood with the sequel of Heathcliff’s history…

‘Both their minds tending to the same point…’

It seems Nelly was summoned to the Heights within a fortnight of Lockwood’s exit. You might recall, Heathcliff was becoming a bit unhinged. And, Lockwood witnessed him muttering about Hareton favoring Catherine (Earnshaw). According to Nelly, it seems he had become entirely annoyed by the mere presence of Cathy, so he requested Nelly keep her in the parlour, making it into a sort of sitting room.

Heathcliff, becoming more morose as the days wore on, wanted the house to himself. Everyone—Joseph, Nelly, Cathy and Hareton—congregated in the kitchen and soon, an adolescent flirtation commenced between Cathy and her cousin. It began as oddly as one might expect—threats of necks being broken and books being thrown.

Only after Hareton was ‘condemned to the fireside’ after a hunting accident, did he warm to his pretty little cousin. According to Nelly, “Mr. Heathcliff, who grew more and more disinclined to society had almost banished Earnshaw from his apartment.” We learn a few paragraphs later, Hareton has made Heathcliff angry: defending sweet, yellow-haired Cathy, ‘a hundred times.’ When Cathy learns this, she gives Hareton a kiss on the cheek. She then asks Nelly to give him a gift: a neatly wrapped book.

Hareton resists her flirtations.

When finally she asks, “…you’ll be my friend?” Did you wonder if Hareton’s reply to her is something he learned to fear from Heathcliff? Remember Heathcliff’s lesson, to avoid extra-animal (human) feelings? Heathcliff is likely still under the impression he had been unworthy of marrying Catherine; he heard her tell Nelly that marrying him would, ‘degrade her.’ Perhaps he taught Hareton to resist falling in love with someone above his station?

“Nah! you’ll be ashamed of me every day of your life,” Hareton tells Cathy, “And the more, the more you know me, and I cannot bide it.” But like her mother, she is much too fond of Hareton and so she continues to try to convince him her affection is real. Nelly tells Lockwood their combined desires—‘one loving and desiring to esteem and the other loving and desiring to be esteemed’—aroused the mutual admiration he’d witnessed upon his arrival.

‘A few yards of earth…’

The beginning of the next chapter—the second of our final three—reminds me of my recognition that Heathcliff (while characterized as more ruffian than gentleman) was at his essence, submissive to Catherine. Hareton, too, it seems, cannot say no when it comes to granting any proposed wish of Cathy’s:

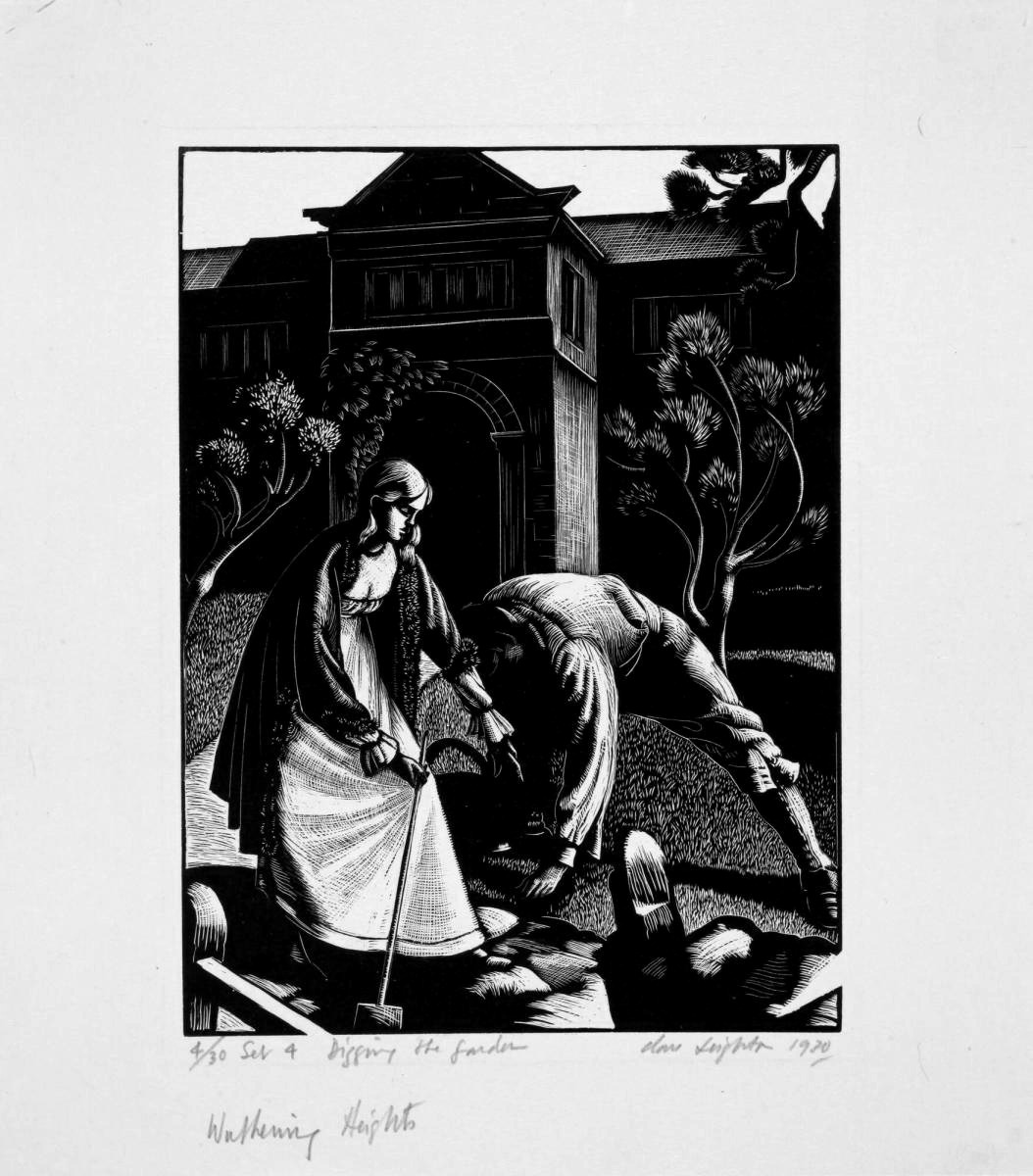

“I saw she had persuaded him to clear a large space of ground from currant and gooseberry bushes, and they were planning together an importation of plants from the Grange.”

Hareton, in a brief half hour, has dug up Joseph’s black currant trees. And Nelly is terrified. Not only does she fear Joseph’s reaction, but retribution suffered at the hands of Heathcliff is likely to be much worse.

When they gather for their meal, Cathy acts as any flirtatious eighteen-year-old girl might, she sidles up next to Hareton and teases him, ‘sticking primroses in his plate of porridge.’ Heathcliff’s mind is elsewhere…until he hears a muffled laugh from ‘his lad’ Hareton. When he surveys the table, Cathy returns his gaze: half-nervous, half-defiant.

The young girl’s Catherine-like gaze rattles him. Believing Catherine’s daughter is the source of audible jubilance, he thunders, “What fiend possesses you to stare back at me, continually, with those infernal eyes? Down with them! and don’t remind me of your existence again. I thought I had cured you of laughing!”

Hareton—just as Heathcliff would have done—takes the blame. He volunteers, “It was me,” and surprisingly, his master resumes eating his breakfast, lost in thought.

It is only when Joseph arrives, with ‘his quivering lip and furious eyes,’ and begins ranting about his currant bushes, Heathcliff’s attention is roused. Hareton quickly admits to removing the bushes but promises to reset them—then Cathy takes the blame for the incident. “We wanted to plant some flowers there,” she initially says, but adds, “I’m the only person to blame, for I wished him to do it.”

Do you remember when we first met young Catherine Earnshaw and the foundling, Heathcliff? Nelly Dean told Lockwood that Catherine fostered a ‘naughty delight’ in provoking her father (Old Mr. Earnshaw)—‘…showing how her pretended insolence had more power over Heathcliff than [Earnshaw’s] kindness: how the boy would do her bidding in anything, and [Earnshaw’s] only when it suited his own inclination.’

While we all recognize Heathcliff is hardly being kind to Hareton, Heathcliff believes the boy reveres him. Cathy exhibiting more power over Hareton than Heathcliff is too much for him to accept. The next episode (in my opinion) provides us with a glimpse into ‘a strange change’ that is approaching:

His black eyes flashed; he seemed ready to tear Catherine to pieces…he shifted his grasp from her head to her arm, and gazed intently into her face. Then, he drew his hand over his eyes, stood a moment to collect himself apparently, and turning anew to Catherine, said with assumed calmness—

“You must learn to avoid putting me in a passion, or I shall really murder you, some time! Go with Mrs. Dean, and keep with her, and confine your insolence to her ears. As to Hareton Earnshaw, if I see him listen to you, I’ll send him seeking his bread where he can get it! Your love will make him an outcast, and a beggar.1 Nelly, take her, and leave me, all of you! Leave me!”

Heathcliff joins the three for dinner but he speaks to no one, eats very little and leaves directly afterwards, telling them he will not return before evening. In his absence, we discover Hareton’s loyalty to Heathcliff remains steadfast.

After Cathy disparages Heathcliff and his treatment of Edgar Linton, Hareton tells her he will stand by Heathcliff even, ‘if he were the devil;’ suggesting he’d rather she revert back to her teasing and her abuse of him (Hareton), than mistreat Heathcliff.

Cathy, confessed later to Nelly, she regretted raising a bad spirit between them and since, she never ‘breathed a syllable—against her oppressor.’

‘A dreadful collection of memoranda’

In previous essays I have confessed: I love Heathcliff. This read-along is called Read With Me and so essentially, participants are simply reading alongside me. Few share their opinions, so I don’t have any idea if you are enjoying the book or loathe it. This chapter—this insight into Heathcliff’s state of mind during the events of this second-to-last chapter—this is why, I love Heathcliff. He breaks my heart. I know he has done horrible things (unforgiveable things), and yes, for that, he does earn readers’ outrage.

It has been suggested Heathcliff is a fictive characterization of Emily Jane Brontë. She exhibited many of his characteristics (at least, according to her myriad biographers). A lover of walking on the moors, she cared little for others’ opinions and seldom graced anyone with a (pleasant) gaze from her ‘half-tamed,’ dark grey-blue eyes.

Emily believed that people should act according to the natures they are endowed with, and like animals, carry no blame on earth for their faults.2

Not since adolescent Heathcliff described Catherine as, ‘immeasurably superior’ to everybody on earth, have we heard him express his feelings so ardently as he does in this chapter. When Nelly describes Heathcliff coming home and finding Cathy and Hareton together—disarming him, by their resemblance to Catherine—he takes a book from Hareton, returns it, and simply shoos them out of the kitchen.

And then, he invites his foster-sister, a woman who has known him since he was a boy of only seven-years-old, to remain with him…

“I have lost the faculty of enjoying their destruction, and I am too idle to destroy for nothing…Nelly, there is a strange change approaching—I’m in its shadow at present. I take so little interest in my daily life, that I hardly remember to eat, and drink.”

Heathcliff is not yet forty. He has lived almost eighteen years without Catherine.

“Those two, who have left the room, are the only objects which retain a distinct material appearance to me; and that appearance causes me pain, amounting to agony.”

Heathcliff admits to the anguish he feels, witnessing the love blossoming between eighteen-year-old Cathy and twenty-three-year-old Hareton.

“About her (Cathy) I won’t speak; and I don’t desire to think; but I earnestly wish she were invisible—her presence invokes only maddening sensations.”

While Cathy does not resemble her mother entirely, she acts in the same haughty way.

“He (Hareton) moves me differently; and yet if I could do it without seeming insane, I’d never see him again! You’ll perhaps think me rather inclined to become so,” he added, making an effort to smile, “if I try to describe the thousand forms of past associations and ideas he awakens, or embodies—but you’ll not talk of what I tell you, and my mind is so eternally secluded in itself, it is tempting, at last, to turn it out to another.”

Finally. Heathcliff has smiled. Sort of?

“Five minutes ago, Hareton seemed a personification of my youth, not a human being. I felt to him in such a variety of ways, that it would have been impossible to have accosted him rationally…in the first place, his startling likeness to Catherine connected him fearfully with her.”

Hareton is made in the image of Heathcliff and Catherine.

“That, however, which you may suppose the most potent to arrest my imagination, is actually the least, for what is not connected with her to me?” he asks of Nelly, “And what does not recall her?”

Have you ever thought about Heathcliff as, a man? He is characterized as a villain, a beast, a devil throughout the entire novel. He is a man. And, he grieved the loss of a woman he loves, entirely alone. He has no friends. At least none we know about. He has no family—or, maybe he did, but Mr. Earnshaw scooped him up off the street in Liverpool and essentially kidnapped him. With whom can Heathcliff discuss his grief? No one. And, if you’ve ever grieved someone you love, you agree with every sentiment he shares with Ellen Dean:

“I cannot look down to this floor, but her features are shaped on its flags! In every cloud, in every tree—filling the air at night, and caught by glimpses in every object by day, I am surrounded with her image…”

“The most ordinary faces of men and women—my own features—mock me with a resemblance. The entire world is a dreadful collection of memoranda that she did exist, and that I have lost her!”

When Heathcliff invokes Hareton’s name again, he tells Nelly, “Hareton’s aspect was the ghost of my immortal love, of my wild endeavours to hold my right, my degradation, my pride, my happiness, and my anguish—.”

Hareton is physically, a ‘ghost’ of Catherine. Socially, he embodies all Heathcliff has experienced: degradation at the hands of Hindley, pride exhibited withstanding years of abuse, happiness experienced when he was with Catherine and anguish, when she was lost to him.

Spending time with Hareton—a personification of Heathcliff’s youth in a likeness of Catherine Earnshaw—is an aggravation, rather than a comfort. And, we now learn from Nelly: ‘from childhood [Heathcliff] had a delight in dwelling on dark things, and entertaining odd fancies.’

Nelly surmises Heathcliff suffers from ‘a monomania,’ a disorder characterized by repetitive obsessive thoughts or actions. At the time, monomania was regarded as a partial insanity, as it involved irrational devotion to one subject (or object) only.3

‘I have a single wish…’

Heathcliff is strong and healthy. And Nelly learns, he certainly does not fear death. On the contrary, he views death—whenever it may come—as his reunion with Catherine.

“I have neither a fear, nor a presentiment nor a hope of death. Why should I? With my hard constitution, and temperate mode of living and unperilous occupations, I ought to and probably shall remain above ground, till there is scarcely a black hair on my head. And yet I cannot continue in this condition! I have to remind myself to breathe—almost to remind my heart to beat! And it is like bending back a stiff spring; it is by compulsion that I do the slightest act not prompted by one thought, and by compulsion, that I notice anything alive, or dead, which is not associated with one universal idea. I have a single wish, and my whole being and faculties are yearning to attain it. They have yearned towards it so long, and unwaveringly, that I’m convinced it will be reached—and soon—because it has devoured my existence. I am swallowed in the anticipation of its fulfillment.”

Nelly tells Lockwood, ‘from his general being’ one would never know, ‘conscience had turned his heart to an earthly hell.’ Heathcliff only became ‘fonder of solitude,’ and ‘perhaps still more laconic in company.’

There is a strange change approaching…

‘Night-walking amuses him…’

April 1802

Our final chapter of the novel begins five months before Lockwood’s return…

After Heathcliff confesses his ‘single wish’ to Nelly, he begins to shun the family at meals, absenting himself rather than remaining agitated by Cathy and Hareton.

“Eating once in twenty-four hours seemed sufficient sustenance for him,” according to Nelly Dean. Nelly notices he’s taken to leaving after everyone goes to bed, returning at breakfast. He rambles all the night through…

Heathcliff stood at the open door; he was pale, and he trembled; yet, certainly, he had a strange joyful glitter in his eyes that altered the aspect of his whole face.

Heathcliff is always standing in doors. Now, it seems he is on the threshold of death.

When he attempts to eat with the family Heathcliff is drawn to the window: “We saw him walking, to and fro, in the garden, while we concluded our meal,” Nelly explains to Lockwood: “Earnshaw said he’d go and ask why he would not dine; he thought we had grieved him in some way.”

What Brontë does here is simply brilliant. She humanizes Heathcliff: “He bid me off to you,” Hareton tells Cathy, perplexed, “He wondered how I could want the company of any body else.”

This dialogue is slipped into the story a moment before Nelly likens him to what can only be characterized as vampiric: he resembles one, undead. He remains outside for an hour or two and when he returns, she tells Lockwood, he displays: “an unnatural appearance of joy under his black brows; the same bloodless hue (as before) and his teeth visible, now and then, in a kind of smile…”

She describes his overall demeanor as: his frame shivering, not as one shivers with chill or weakness, but as a tight-stretched cord vibrates—a strong thrilling, rather than a trembling.”

Is Brontë purposefully taking the vampire trope further when she has Nelly comment on Heathcliff looking ‘uncommonly animated?’ Especially so, when he replies: “I’m animated with hunger; and seemingly, I must not eat.” Maybe a bit, but what I think Brontë is actually clarifying is that Heathcliff is mobilized toward his goal:

He is hungry for his reunion with Catherine. Taking nourishment will only delay his objective.

‘Is he a ghoul or a vampire?’

Heathcliff smiling was a surprise. Now, he interrupts with a laugh.

“Last night, I was on the threshold of hell. To-day, I am within sight of my heaven. I have eyes on it—hardly three feet to sever me! And now you’d better go. You’ll neither see not hear anything to frighten you, if you refrain from prying.”

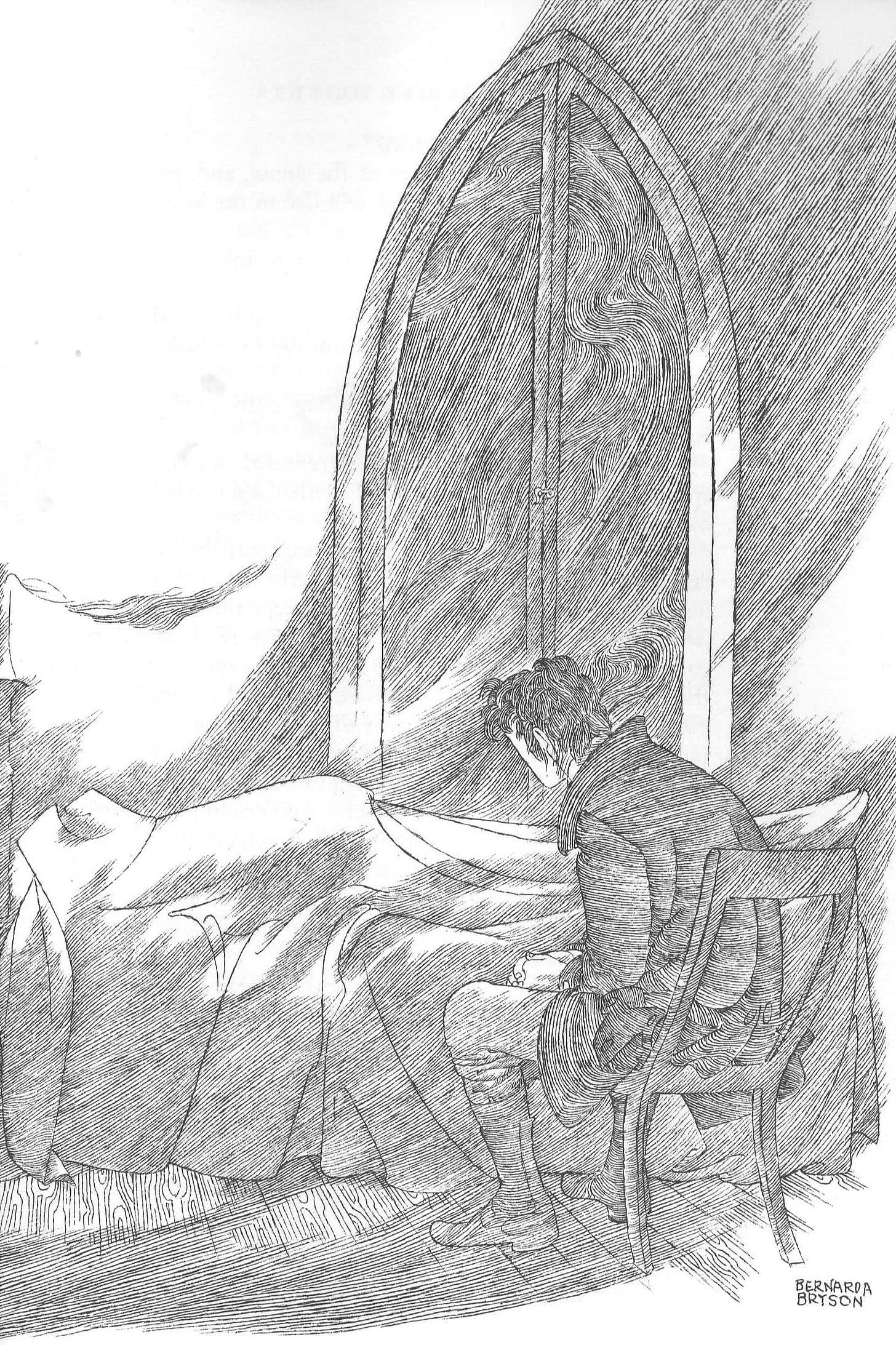

Heathcliff recognizes Ellen Dean has—throughout the years—seen and heard much to frighten her. On his urging, she leaves him to his solitude. That is, until eight o’clock that evening, when she, ‘unsummoned [carries] a candle and his supper to him.’

He was leaning against the ledge of an open lattice, but not looking out; his face was turned to the interior gloom. Again, Heathcliff stands in a liminal space. The fire had smouldered to ashes; the room was filled with the damp, mild air of the cloudy evening, and so still, that not only the murmur of the beck down Gimmerton was distinguishable, but its ripples, and its gurgling over the pebbles, or through the large stones which it could not cover.

When the sky is overcast, sound travels great distances. Emily Brontë would have known this and she uses it; she also reminds us of the fateful scene in which Edgar and Catherine stand at the window, gazing out toward Wuthering Heights.4

Were you also reminded of the scene in which Catherine—during her last illness—sits at the window, listening. It was March, remember?

Gimmerton chapel bells were still ringing; and the full, mellow flow of the beck in the valley came soothingly on the ear…at Wuthering Heights it always sounded on quiet days, following a great thaw or a season of steady rain; and of Wuthering Heights, Catherine was thinking as she listened—that is, if she thought, or listened at all—but she had the vague, distant look…which expressed no recognition of material things by ear or by eye.5

Heathcliff also has a vague, distant look, and Nelly Dean rouses him by inquiring, “Must I close this?” motioning to the window. Brontë treats us to more vampiric imagery:

The light flashed on his features…those deep black eyes! That smile, and ghastly paleness! It appeared to me, not Mr. Heathcliff, but a goblin; and in my terror, I let my candle bend towards the wall, and it left me in the darkness.

It’s a bit amusing, isn’t it, when Nelly admits Heathcliff replies to her in a familiar voice—“There, that is pure awkwardness!”—in other words, he is not a goblin. In fact, she muses, she asks herself—Is he a ghoul or a vampire? Nelly ‘has read of such hideous, incarnate demons.’ She reminds herself, she tended to him as a child. And, she scolds herself for, ‘[yielding] to that sense of horror.’

But where did he come from, the little dark thing, harboured by a good man to his bane? Nelly drifts off to sleep, ‘imaging some fit parentage for him,’ she recalls his existence, with ‘grim variations,’ and finally, she pictures Heathcliff’s death and his funeral. She tells Lockwood, she lay half-asleep, worrying about her master’s lack of a surname, tasked with dictating an inscription on his monument.

‘Are we by ourselves?’

May 1802

Heathcliff’s behavior continues to concern Nelly. Yet, most of the time he acts as sane as any master or land-owner. I wonder why Nelly never viewed Hindley’s behavior—shoving a knife between her teeth, threatening to kill her or, dropping his son from a balcony, as reason for concern?; but Heathcliff, finally smiling and at peace, unnerves her.

When Heathcliff is observed, resting his arms on the table, looking at a wall opposite him, ‘surveying one particular portion, up and down, with glittering eyes, and with such eager interest, that he stopped breathing, during half a minute,’ his smile is so unsettling Nelly accuses him of seeing, ‘an unearthly vision.’

“Turn around,” he instructs, “and tell me, are we by ourselves?”

He continues to gaze at something—in fact, not the wall—two yards in front of him. It communicates (whatever it is), ‘both pleasure and pain, in exquisite extremes.’ The object is not fixed, it is an apparition which, ‘with unwearied vigilance,’ Heathcliff cannot look away from, even when speaking with Nelly. She reminds him to eat, but clenching his fingers closed before reaching a piece of bread, he remains fixated on an ‘engrossing speculation.’

Heathcliff leaves and saunters down the garden path; returning after midnight, he paces the lower room. Nelly hears him muttering to Catherine, ‘some wild term of endearment or suffering—low and earnest, and wrung from the depth of his soul.’

Ever-the-meddler, Nelly arrives downstairs and Heathcliff requests she make him a fire. He wishes to call a lawyer as soon as day breaks, to write a will. “I wish I could annihilate it from the face of the earth,” he admits, referring to all of his property.

A moment ago, Heathcliff was speaking to the dead and now, he is getting his affairs in order. I cannot help but be impressed by how effortlessly Brontë describes this: I’m certain she had experienced it. The lucidity expressed by the dying is unlike anything imaginable, unless it’s experienced first-hand. When my dad was dying he described in great detail, seeing and speaking with his deceased father. Within minutes he was able to discuss matters of the household or, odds and ends which required attention. And in a few days more, he slipped into unconsciousness.

Dramatization combined with Gothic elements permit us to suspend our disbelief and accept Heathcliff as death incarnate. His soul has been underground for these eighteen years. Brontë reminds us (again) of his vampiric features:

“Do take some food, and some repose,” Nelly begs, “You need only look at yourself in a glass to see how you require both. Your cheeks are hollow, and your eyes blood-shot, like a person starving with hunger, and going blind with loss of sleep.”

We wonder: if Heathcliff gazed in a looking-glass, would he have a reflection?

“My soul’s bliss kills my body, but does not satisfy itself,” Heathcliff explains. What do you believe he means? My interpretation is this: Heathcliff is entirely delighted to be so close to spending eternity with Catherine, but his bliss is not enough to sustain his body—yes, food and rest are required, but he will rest soon enough.

While our minds return to the question of whether Heathcliff is some unchristian devil, Nelly suggests maybe he might desire to speak with a minister—to get right with God before he dies. Otherwise, he will remain unfit for her Christian heaven.

“You remind me of the manner that I desire to buried in,” he tells her. “It is to be carried to the churchyard, in the evening.” He adds, “You and Hareton may, if you please accompany me—and mind, particularly, to notice that the sexton obeys my directions concerning the two coffins! No minister need come; nor need anything be said over me.” He clarifies, “I tell you, I have nearly attained my heaven; and that of others is altogether unvalued and uncoveted by me!”

Nelly, designating his ‘obstinate fast,’ a suicide, threatens the sexton may refuse to bury him, ‘in the precincts of the Kirk.’ Brontë slips a bit of the supernatural into the exchange. Heathcliff tells Nelly if that should happen, she must have him disinterred and if she neglects to do so, she risks proving, “that the dead are not annihilated!”6

Heathcliff continues to unnerve Nelly. He enters the kitchen and requests she come and sit with him; she declines, admitting, she has ‘neither the nerve nor will to be his companion.’ Then, he invites Cathy’s companionship. When she shrinks, he owns, “No! to you, I’ve made myself worse than the devil.”7 He solicits no one else’s society after declaring, “Well, there is one who won’t shrink from my company! By God! she’s relentless. Oh, damn it! It’s unutterably too much for flesh and blood to bear, even mine.” And, after making this allusion to Catherine’s ghost, he retires to his chamber and locks the door. There, he remains. Through one whole evening and ‘far into the (next) morning,’ according to Nelly.

We are nearing the conclusion of The Story of Heathcliff…

‘Th’ divil’s harried off his soul…’

In the last few days, Heathcliff has settled his affairs. He confessed to Nelly that he couldn’t care less about the future of his properties.8 He’s acknowledged Hareton’s feelings for Cathy; and personally extended a small gesture of kindness toward her.

After Heathcliff locks himself in his chamber, two nights pass. The second night it rains—into the next morning. And when Nelly Dean takes her morning walk she is alarmed to see her master’s window ‘swinging open, and the rain driving straight in.’

Inside the box bed he once shared with Catherine, ‘Heathcliff was there—laid on his back.’ Nelly describes the scene: “His eyes met mine so keen and fierce, I started; and then he seemed to smile.9 I could not think him dead, but his face and throat were washed with rain; the bedclothes dripped, and he was perfectly still.”

In this next statement we harken back to Lockwood in the first chapters.10 Rather than the ghost-child Catherine’s wrist sliced on the window pane, Heathcliff is cut.

“The lattice, flapping to and fro, had grazed one hand that rested on the sill;

Unlike the ghost of Catherine, Heathcliff does not bleed.11

“…no blood trickled from the broken skin, and when I put my fingers to it, I could doubt no more—he was dead and stark!”

Nelly closes the window and combs Heathcliff’s ‘black long hair from his forehead and tries to close his eyes—“to extinguish,” she tells Lockwood, “that frightful, life-like gaze of exultation…” They do not close. She claims they sneer at her attempts.

In one last vampiric nod, Nelly declares:

“His parted lips and sharp, white teeth sneered too!”

An understandably disturbed Mrs. Dean eventually requests Joseph’s aid and when, ‘the old sinner’ sees the corpse he cries:

“Th’ divil’s harried off his soul, and he muh hev his carcass intuh t’ bargain, for ow’t Aw care! Ech! what a wicked un he looks grinning at death!”12

Then, Joseph thanks God that the lawful owner (Hareton) is restored to the Heights.

Sadly, Hareton is not as delighted to lose Heathcliff. He sits by the corpse all night, ‘weeping in bitter earnest.’ “He pressed its hand, and kissed the sarcastic, savage face that every one else shrank from contemplating; and bemoaned him with that strong grief which springs naturally from a generous heart, though it be tough as tempered steel.”

Lockwood learns, when Kenneth—the doctor—was called, no clear cause of death could be determined.13 Nelly enlightens him, “We buried him, to the scandal of the whole neighborhood, as he had wished.” Only Earnshaw and Nelly, a sexton and six men (to carry the coffin) attended the burial. Cathy and Joseph likely declined.

‘Heathcliff and a woman, yonder, under t’ Nab’

Emily Brontë is wise to make Nelly confirm, “The six men departed when they had let it down into the grave: we stayed to see it covered.” She adds, “Hareton, with a streaming face, dug green sods, and laid them over the brown mould himself. At present it is as smooth and verdant as its companions.”

Lowered into the grave, and entirely covered. Ellen Dean saw Heathcliff’s body has been properly interred (as he wished). Hareton cut sod and laid it over the bare earth. Today, September 1802—four months later—the plot is as green and undisturbed as Edgar’s, dug one year ago and Catherine’s, nearly two decades old.

Why then, might Nelly hope, ‘its tenants sleep soundly?’

“The country folks, if you asked them, would swear on their Bible that he walks.”

Nelly makes a clear distinction between herself and ‘country folk.’ She tells Lockwood that although some have said they’ve met Heathcliff’s ghost, “near the church, and on the moor, and even within [the] house,” those are idle tales. Proving a good Christian to the end, Mrs. Dean also aims to distinguish herself from, ‘that old man by the kitchen fire (Joseph),’ who is convinced he sees Heathcliff and Catherine, ‘every rainy night.’

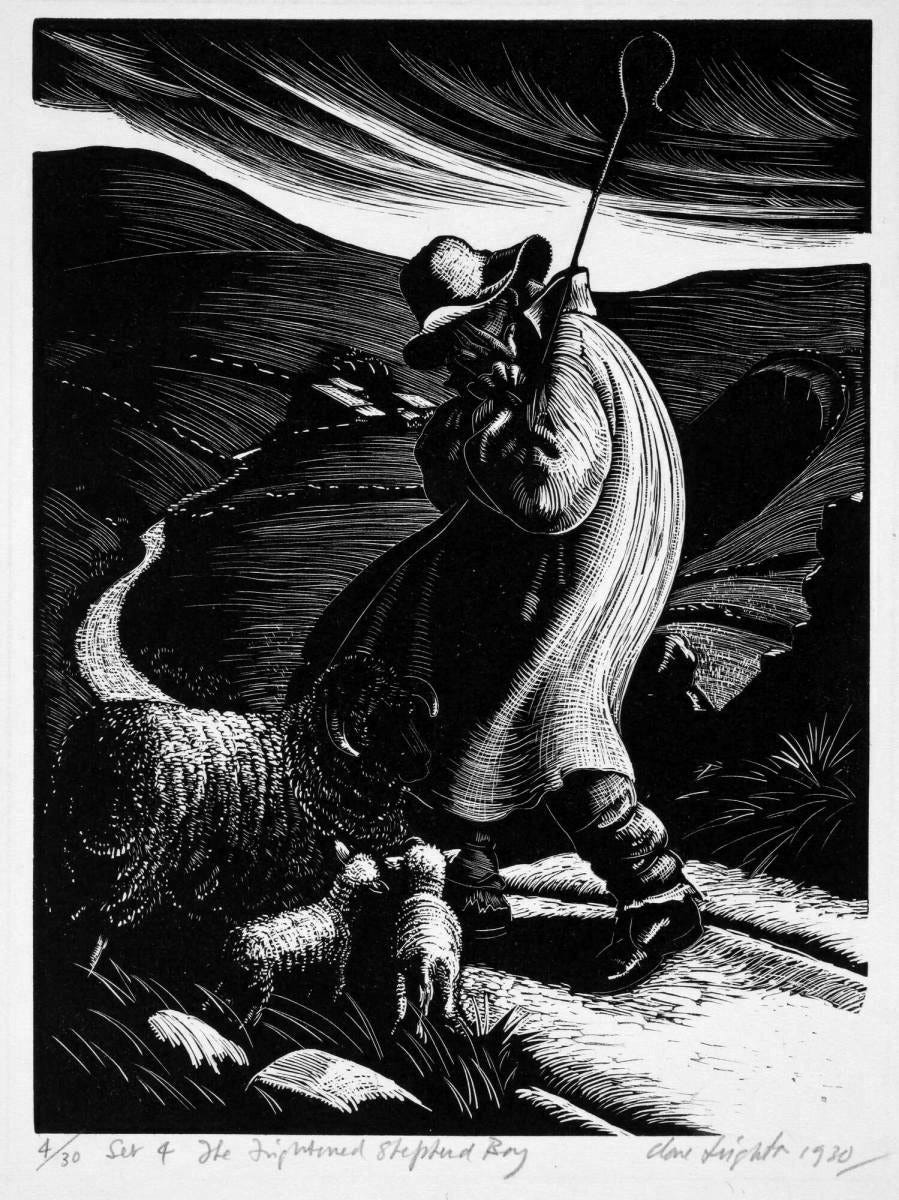

Emily Jane Brontë provides us with one final ghost story, when Nelly Dean tells Lockwood about meeting the frightened shepherd boy:

I was going to the Grange one evening—a dark evening threatening thunder—and, just at the turn of the Heights, I encountered a little shepherd boy with a sheep and two lambs before him; he was crying terribly, and I supposed the lambs were skittish, and would not be guided.

When Nelly asked the boy what was the matter, he explained: “They’s Heathcliff and a woman, yonder, under t’ Nab, un Aw darnut pass ‘em.” Despite her protestations, that spirits walk the earth, Nelly Dean tells Lockwood she instructed the boy to take an alternate road. She attempts to reason that the boy likely ‘raised the phantoms’ by his own imagination, but she confesses: “I don’t like being out in the dark, now; and I don’t like being left by myself in this grim house…”

She tells Lockwood Hareton Earnshaw and Catherine Heathcliff are to be wed on New Year’s Day. They will move to the Grange, taking Ellen Dean along with them. Joseph will remain at Wuthering Heights, living in the kitchen, and the rest of the house will be ‘shut up.’

Much to Nelly’s chagrin, Lockwood quips: “For the use of such ghosts who wish to inhabit it.” The city-dwelling folklorist observer is scolded by our teller of tales, the old wife. Almost as if, to convince herself, Nelly declares: “I believe the dead are at peace…it is not right to speak of them with such levity.”

At this very moment, and I can’t help but think this is on purpose, the garden gate swings open and the ramblers return—Hareton and Cathy, not the ghostly spectres, Heathcliff and Catherine.

And then, just as weirdly and awkwardly as our story began, Lockwood expresses his envy at an inability to attain beautiful young Cathy, who would rather give her love to a boorish young man, who only recently was functionally illiterate. Lockwood groans: “They are afraid of nothing. Together they would brave Satan and all his legions.”14

'In that quiet earth’

Gimmerton Kirk—where Edgar Linton married Catherine Earnshaw—is in decay.

Many a window showed black gaps deprived of glass; and slates jutted off, here and there, beyond the right line of the roof, to be gradually worked off in coming autumn storms.

Next to the moor, Lockwood discovers three headstones. The middle one, grey, and half buried in heath—Edgar Linton’s only harmonized by the turf, and moss creeping up its foot—Heathcliff’s still bare. Half-buried in heath. Isn’t that brilliant?

“I lingered round them, under that benign sky; watched the moths fluttering among the heath, and hare-bells; listened to the soft wind breathing through the grass; and wondered how any one could ever imagine unquiet slumbers for the sleepers in that quiet earth.”

Tell Me…Love It? Hate It? Let Me Know!

If you’ve finished reading Wuthering Heights with me, and you feel comfortable sharing your thoughts on the novel, please reach out. The book requires little time to read, but for first-time readers the material is sometimes difficult to navigate. I hope you agree my weekly summaries have contributed to your comprehension of the novel.15

Remember when Heathcliff believed Hareton would remain “safe from [Cathy’s] love?”

“Emily Jane Brontë.” The Oxford Companion to The Brontës. Ed. Christine Alexander and Margaret Smith. Oxford University Press. 2018.

Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights: A Norton Critical Edition (Fifth Edition). Edited by Alexandra Lewis, 5th ed., W. W. Norton & Company. 2019.

I think my attention to Wuthering Heights may qualify as a monomania; or, perhaps my fascination with Heathcliff. The term was coined in 1810 but fell into disuse by 1850.

Volume 1: Chapter 10

Volume 2: Chapter 1 (or, 15)

He will return to haunt her.

In this scene, Heathcliff uses a Yorkshire term of endearment, chuck, to refer to Cathy.

“I wish I could annihilate it from the face of the earth.”

He only seems to smile; but re-animation really ticks the Gothic box, no?

Volume 1: Chapter 3

Did Lockwood’s dream-ghost of Catherine bleed because Heathcliff still lived?

“The devil has carried off his soul, and he may have his (body) in the bargain, for all I care! Ech! What a wicked one he looks grinning (scornfully) at death!”

Heathcliff has not taken nourishment for four days; a healthy person can survive four days without food (and even, water). Brontë is certainly implying the supernatural death was a willful one.

Were you reminded of Catherine Earnshaw in her delirium, speaking of the Gimmerton Kirk churchyard: “We’ve braved its ghosts often together, and dared each other to stand among the graves and ask them to come.”

Spring 2025 read-along essays will be paywalled on June 20, 2025 (Summer Solstice).

Yes! What a perfect ending. Your summaries helped greatly, and it is fun knowing some of your thoughts about the book. I must-have looked at the family tree about a hundred times in the first section of the book.

This is a big question, and point me to the right blog post if you've answered it, but what drew you to reread Wuthering Heights instead of the other books you've read?