Hello! Welcome to Week Seven of our Wuthering Heights read-along…

This week’s assignment is Volume II: Chapters VIII-XIII

This week’s reading assignment spans six chapters and comprises thirty-six pages. Honestly, it’s a portion of the story which is challenging to navigate. Why has Brontë put so much effort into describing the courtship between Linton Heathcliff and Cathy Linton when she provided us with so little detail regarding Heathcliff and Catherine Earnshaw’s adolescence? It’s complicated…

What Happens in Chapters VIII-XIII?

Our first chapter begins with a timestamp—Summer drew to an end, and early Autumn: it was past Michaelmas. Michaelmas, the feast of St. Michael and All Angels is recognized on 29 September. Marking the end of one season and the induction of the next, it is customary, for the harvest to be completed.

Saint Michael is one of the principal angelic warriors, protector against the dark of the night and the Archangel who fought against Satan and his evil angels.

As Michaelmas is the time that the darker nights and colder days begin – the edge into winter – the celebration of Michaelmas is associated with encouraging protection during these dark months.

It was believed that negative forces were stronger in darkness and so families would require stronger defences during the later months of the year.1

In England, Michaelmas is one of four recognized quarter-days.2 In 1800, the year of this chapter’s late harvest, the autumnal equinox fell on the 23rd and so, a full Harvest Moon would have occurred on the 20th.

I wonder if Emily Brontë kept all of this in mind when she shared an allusion to time with her readers? If you recall, the return of Heathcliff to the neighborhood was under the Harvest Moon and this second volume of The Story of Heathcliff makes readers feel like we are plunging into the darker months and every character will require stronger defenses. The chapter begins with the loveliest nature imagery thus far; unfortunately Miss Cathy is sullen…

‘On an afternoon in October’

“Mr Linton and his daughter would frequently walk out among the reapers;” Nelly explains to Lockwood. They would do this, “at the carrying of the last sheaves.”

“[Edgar and Cathy] stayed till dusk, and the evening happening to be chill and damp, my master caught a bad cold.” This is a charming explanation for what was likely pneumonia. Nelly, like my own Gram, simply blames the weather for a cold.

Edgar was, “confined—indoors throughout the whole of the winter, nearly without intermission.” And Cathy was without a walking companion. Still melancholy after learning her father and Heathcliff are at odds and she may no longer correspond with her cousin, Linton, she became, ‘considerably sadder and duller.’ Edgar insisted she read less, and take more exercise (out of doors).

On an afternoon in October, or the beginning of November, a fresh watery afternoon, when the turf and paths were rustling with moist, withered leaves, and the cold, blue sky was half hidden by clouds, dark grey streamers, rapidly mounting the west, and boding abundant rain…

Cathy wishes to take a walk. Begrudgingly Nelly agrees and umbrella-in-hand, she sets out to accompany Miss Linton to some of the young lady’s favorite haunts.

On one side of the road rose a high, rough bank, where hazels and stunted oaks, with their roots half exposed, held uncertain tenure: the soil was too loose for the latter; and strong winds had blown some nearly horizontal. In summer, Miss Catherine delighted to climb along these trunks, and sit in the branches, swinging twenty feet above the ground…from dinner to tea she would lie in her breeze-rocked cradle, doing nothing except singing old songs…watching the birds, joint tenants, feed and entice their young ones to fly…half thinking, half dreaming, happier than words can express.

Nelly is thinking of Cathy in happier times and in an attempt to cheer her, she points to a nook under the roots of a tree. “Winter is not here yet. There’s a little flower, up yonder, the last bud from the multitude of blue-bells that clouded those turf steps in July with a lilac mist. Will you clamber up, and pluck it to show to papa?”

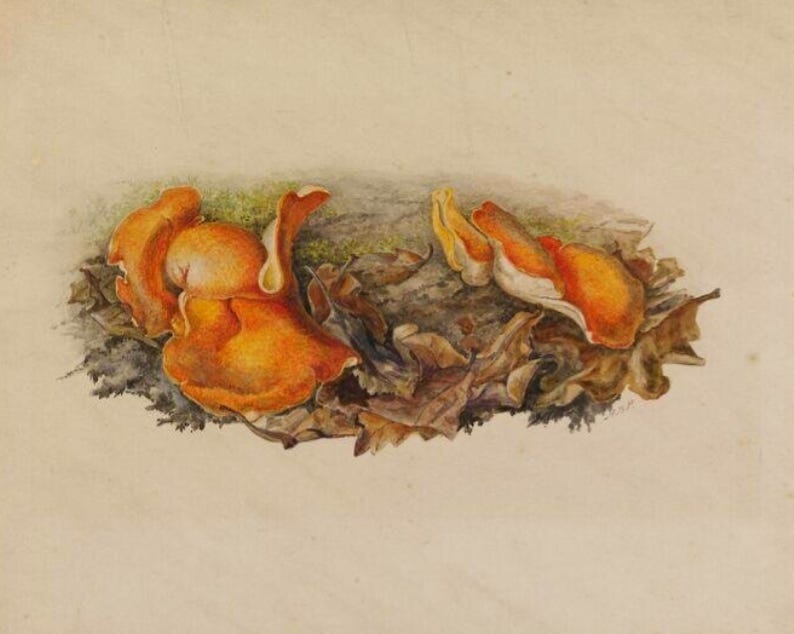

Brontë, who knows her land and understands myriad stages of grief, writes that Cathy stared a long time at the ‘lonely, blossom trembling in its earthy shelter.’ Refusing to pick it, she saunters on, ‘pausing, at intervals, to muse over a bit of moss, or a tuft of blanched grass, or a fungus spreading its bright orange among the heaps of brown foliage; and ever and anon, her hand was lifted to her averted face.’3

It is in this scene we learn Cathy is afraid her father (and Nelly!) will leave her alone in the world. Her father is ill (though, he is only thirty-eight) and the only other person to care deeply for her is Ellen Dean, who is ‘hardly forty-five;’ but to Cathy, who lost her mother and now her aunt, mortality weighs heavily on her mind.

‘On the summit branches of the wild rose trees’

After Nelly calms Cathy’s fears, and Cathy declares: “I love [papa] better than myself, Ellen; and I know it by this: I pray every night that I may live after him, because I would rather be miserable than that he should be—that proves I love him better than myself.”

The elder Catherine, at this age, loved only Heathcliff. And she loved Heathcliff as she loved herself. Not better than herself but, as herself. I am Heathcliff. She wished to hold him until they were both dead. The object of her unnatural love—Heathcliff—still, in 1800, wanders the earth with his soul, ‘in the grave.’

As Cathy and Nelly continue sauntering along they come to, ‘a door that opened on the road;’ and Cathy climbs up onto the top of the wall, ‘reaching over to gather some hips that bloomed scarlet on the summit branches of the wild rose trees, shadowing the highway side; the lower fruit had disappeared, but only birds could reach the upper, except from Cathy’s present station.’ Her hat falls off and because the door is locked she scrambles down over the wall to retrieve it. Nelly explains to Lockwood, ‘the return was no such easy matter; the stones were smooth and neatly cemented,’ adding, ‘the rosebushes and blackberry stragglers could yield no assistance in re-ascending.’

As readers we are at ease, Cathy is laughing and dancing and we are relieved she is no longer burdened with the notion her father may die. Ah! But, Michelmas is past…

All need stronger protection from dark forces.

‘On the road to Wuthering Heights…’

When Heathcliff meets Cathy on the road, he does not know Nelly Dean is just over the wall. He tells Cathy, Linton is unwell and if she does not rekindle her relationship with him, he will certainly die.

Nelly calls over the wall, admonishing her charge to consider: “it is impossible that a person should die for love of a stranger.”

Heathcliff scolds Nelly for allowing Cathy to believe he hates her father and her, too. He accuses Nelly of ‘inventing bugbear stories to terrify her from [his] door-stones.’ What is a bugbear, you may ask? A bugbear is a nursery bogie. A nursery bogie—or boogeyman—is the subject of stories created to frighten children into good behavior.

I wonder, did Nelly once use such stories to make Catherine and Heathcliff behave?

Well, as you know, Heathcliff’s tale about Linton dying outweighs any bugbear stories previously invented by her nurse and Cathy is overcome with concern for her cousin; Nelly agrees they must go and visit the Heights.

‘You can’t alter what you’ve done!’

The next chapter allows us a shocking glimpse into the personality and behavior of Linton Heathcliff after residing at Wuthering Heights for three years (1797-1800).

Remember, he has not corresponded with Cathy for approximately three months. On this morning it is misty—half frost, half drizzle. By the time they arrive at Wuthering Heights, Nelly has become ‘thoroughly wetted,’ her shoes are soaked through, from crossing ‘temporary brooks…gurgling from the uplands.’

When we find Linton he snarls a threat, believing the approaching footsteps to be those of Joseph: “Oh, I hope you’ll die in a garret! starved to death!” The visitors from the Grange find him sitting in a chair, complaining of being cold. Nelly tells Lockwood that she ‘stirred up the cinders,’ and fetched a scuttle-full of coal.

Though she admits, Linton ‘had a tiresome cough and looked feverish and ill.’ When the boy is unappreciative her sympathy wains. Cathy, unsurprisingly, fawns over him, petting his long hair and telling him if she had her father’s consent, she’d spend half her time with him. She tells him she wishes he were her brother. Linton cheers a bit, but confesses: Heathcliff has told him that if Cathy were his wife, she would love him (Linton) more than she loves her father, Edgar.

Isn’t the next episode interesting?

Cathy tells Linton his father hated his mother. Linton confirms Heathcliff has said Edgar is a ‘sneaking fool,’ and Cathy cries, “Yours is a wicked man!” She tells Linton his mother left his father, and Linton divulges that Catherine’s deceased mother hated Cathy’s father and instead, loved Heathcliff!

In a scene reminiscent of the one between Heathcliff and Edgar,4 Cathy hastily gives Linton’s chair a violent push, causing him to fall against one arm. It’s interesting that Brontë aligns Cathy Linton’s behavior with Heathcliff’s in this episode, isn’t it?

Linton is overcome with a suffocating cough—a fit which lasts minutes. When he recovers and Nelly inquires how he feels, Linton groans, “I wish [Cathy] felt as I do, spiteful, cruel thing!” And as Linton continues to whine, we learn, Hareton5 never touches him: “he never struck me in his life.”

The outrageous melodramatic behavior of Linton now mimics Catherine’s adolescent outburst,6 yet it goes beyond her tantrum, doesn’t it? If I’m being honest, reading these passages is difficult. Linton is undoubtedly, as Nelly puts it, “the worst-tempered bit of sickly-slip that ever struggled into his teens!”7

Cathy Linton, because she is Catherine Earnshaw’s child, is intrinsically linked with and exhibits Heathcliff’s behavior. Linton Heathcliff, because he is Heathcliff’s child is intrinsically linked with and exhibits Catherine Earnshaw’s behavior. Tenderness exhibited by both—we must assume—comes from their Linton parentage.

Isn’t it interesting to consider that Edgar Linton (at age eighteen) once witnessed and forgave Catherine Earnshaw’s horrible, violent and bullying behavior—and asked her to marry him? At eighteen, Isabella Linton witnessed and forgave Heathcliff’s brutal behavior—to eventually elope with him. Now, Cathy is witnessing and (like her father) she is forgiving Linton Heathcliff’s ‘grievous and harassing’ behavior.

In fact, Linton asks Cathy to ‘sit on the settle and let me lean on your knee. That’s what mamma used to do…,’ and Brontë reminds us of when old Mr. Earnshaw was dying and Catherine sat at his knee with Heathcliff’s head resting in her lap.8

We are relieved when this chapter ends, aren’t we? I mean, maybe I’m speaking for myself but seriously…spending time with Linton Heathcliff feels like being racked at the Tower of London.9

Nelly Dean, after the visit to Linton (‘sitting such a while at the Heights had done the mischief’), is laid up for three weeks with a cold. Cathy Linton plays nurse to both her father, Edgar, and Ellen Dean. Nelly tells Lockwood:

The moment Catherine left Mr. Linton’s room, she appeared at my bed-side. Her day was divided between us; no amusement usurped a minute: she neglected her meals, her studies, and her play; and she was the fondest nurse that ever watched. She must have had a warm heart, when she loved her father so, to give so much to me!10

Did you catch the bit there at the end of the chapter, after Nelly praises Miss Cathy, when she admits, she had been fooled? “I remarked a fresh colour in her cheeks, and a pinkness over her slender fingers,” she recognizes, however, “instead of fancying the hue borrowed from a cold ride across the moors, I laid it to the charge of a hot fire in the library.”

‘The moon shone bright…’

When our next chapter begins we learn that after Nelly’s three week illness, Cathy’s cagey evening behavior piques the housekeeper’s interest. One evening she waits and watches from the young lady’s bedroom window:

“The moon shone bright; a sprinkling of snow covered the ground and I reflected that [Cathy] might have taken it into her head to walk about the garden—” Nelly explains to Lockwood, “I did detect a figure creeping along the inner fence of the park…on its emerging into the light, I recognised one of the grooms.”

We learn Cathy has been plying Grange groom, Michael—with books and pictures— to prepare Minny for her each evening so she may continue to visit Linton Heathcliff at Wuthering Heights. In exchange for the items, he would prepare and put the pony in the stable. After her easily coaxed confession, Cathy describes an experience with Linton at the Heights:

“One time—we were quarreling. He said the pleasantest manner of spending a hot July day was lying from morning till evening on a bank of heath in the middle of the moors, with the bees humming dreamily about among the bloom, and the larks singing high up over head, and the blue sky and bright sun shining steadily and cloudlessly. That was his most perfect idea of heaven’s happiness.”

Cathy believes Linton’s heaven would be ‘only half alive;’ she would ‘fall asleep.’

“Mine,” Cathy tells Nelly, “was rocking in a rustling green tree, with a west wind blowing and bright, white clouds flitting rapidly above; and not only larks, but throstles, and blackbirds, and linnets, and cuckoos pouring out music on every side, and the moors seen at a distance, broken into cool dusky dells; but close by, great swells of long grass undulating in waves to the breeze; and woods and sounding water, and the whole world awake and wild with joy.”

Linton says her heaven would be ‘drunk’ and ‘he could not breathe.’ Cathy explains, “He wanted all to lie in an ecstasy of peace; I wanted all to sparkle, and dance in a glorious jubilee.”

Remembering the cousins are only imagining what they intend to do in summertime, we must return to indoor amusements. Cathy tells Nelly that idle Linton ‘consented to play ball with [her];’ and the teenagers found two balls in a cupboard, ‘among a heap of old toys: tops, hoops, and battledores and shuttlecocks.’

One ball was, ‘marked C. and the other H.’ “I wished to have the C., because that stood for Catherine,” she explains, “and the H. might stand for Heathcliff, his name; but the bran came out of H., and Linton didn’t like it.” This reminds me of Heathcliff trading his lame colt for Hindley’s.11

Now, let’s talk about Cathy, Linton and Hareton…

‘Thear, that’s t’ father! We’ve allas summut uh orther side in us.’

Cathy is sharing many stories of her adventures at Wuthering Heights. She tells Nelly that on the following evening she met Hareton outside.

He wishes to show her he has learned to decipher the name above the door: Hareton Earnshaw. When she inquires, “And the figures?” however, he tells her he has not yet learned them. She laughs, and calls him a dunce. When she cruelly reminds him she is there only to visit Linton (and certainly not, him)—by the moonlight—she sees his face redden, ‘a picture of mortified vanity.’

Let’s remember, Heathcliff told Cathy he would be ‘away’ for a week. The Heights is occupied by Joseph, Zillah (the new housekeeper), Hareton and Linton. And we know Joseph dotes over Hareton—recognizing him as the rightful owner of the place.

When Hareton enters the parlour and manhandles Linton, declaring, “Get to thy own room! Take her there if she comes to see thee—thou shalln’t keep me out—Begone, wi’ ye both!” he has an ally in his anger. He tosses Linton bodily out of the room and Cathy follows. When she drops one of her books, Hareton kicks it—showing readers his recognition that bolstering his intellect is not enough to impress Miss Linton.12

Imprisoned in the kitchen (compare with Catherine and Heathcliff when Hindley banished them),13 rather than plan to escape outside (to ramble at liberty), Linton fights to be let deeper inside. Grasping and rattling the door handle, he shrieks: “If you don’t let me in, I’ll kill you! If you don’t let me in, I’ll kill you! Devil! devil! I’ll kill you!”

Joseph is delighted and remarks (I’ll translate): There, that’s the father! That’s the father (in him)! We’ve always something of either side in us. Like Nelly Dean, the servant Joseph cannot always decide to whom he is loyal.14

Cathy tells Nelly she attempted to calm Linton but he instead had another coughing fit, this time coughing up blood, and Hareton carried the boy to his bedroom. Zillah assured Cathy that Linton would be fine but the girl would not calm—and when she told Hareton he will hang (for the murder) of Linton, Hareton began to sob. Can you imagine such a scene? And when Cathy finally escaped the Heights, Hareton ‘issued from the shadow of the road-side’ and checked Minny.

Hareton, forgetting Heathcliff’s lessons to avoid extra-animal feeling, confesses he is ‘ill-grieved.’ Instead of empathy from Miss Linton, he gets a lash from her whip. And, he is taught there is no value in expressing remorse or issuing an apology. Unless, of course, you are ‘pretty’ Linton. Pretty Linton is forgiven for his atrocious behavior.15

At the end of this depressing and disheartening chapter we learn Heathcliff is pleased he has managed to manipulate all parties involved and, Edgar Linton has forbidden his teenage daughter from visiting the Heights. We carry on into 1801…

‘Musing by myself among those stones…’

At the beginning of this chapter,16 it is 1801 and we have found ourselves firmly back within Lockwood’s room at the Grange. Nelly is confirming that the events she’s just shared have taken place a season ago—‘last winter’—and she is strangely surprised to be divulging these details to an outsider.

The first few paragraphs are written as Lockwood and, we readers, are told, “it may be very possible that [Lockwood] should love Cathy Linton,” (wait. what?). He asks, “But would she love me?” If you’re wondering how Lockwood fell in love with someone he met once, someone who was not particularly kind to him, you are not alone.

The short exchange between Ellen Dean and Mr. Lockwood moves the story along…

Lockwood inquires if Cathy remained ‘obedient to her father’s commands?’ Nelly tells him that, in fact, the young lady did behave. “Her affection for [Edgar] was still the chief sentiment in her heart;” Nelly declares. And then, we get the feeling she strives to separate Edgar from Heathcliff: “He spoke without anger.”17

“He spoke with a deep tenderness of one about to leave his treasures amid perils and foes,” explains Nelly, surmising, “where his remembered words would be the only aid that he could bequeath to guide her.”

Emily Brontë, before continuing her narrative, shares with readers the sentiment now in Edgar’s heart—his health now rapidly declining, the end of his life, near. Remember this passage as you continue to read Wuthering Heights and compare with Heathcliff in a future chapter.18

It was a misty afternoon in February (1801) and walking to the window to gaze out on Gimmerton Kirk, Edgar confesses to Nelly:

“I’ve prayed often for the approach of what is coming; and now I begin to shrink, and fear it. I thought the memory of the hour I came down that glen a bridegroom would be less sweet than the anticipation that I was soon, in a few months, or possibly, weeks, to be carried up, and laid in its lonely hollow!”

I think it’s important to keep in mind here: Catherine Earnshaw and Edgar Linton were married in Summer 1783 and their union was consummated; Cathy was born premature the following March, ‘a seven months child.’

Heathcliff returned in September 1783 and created the estrangement between Edgar and Catherine, out of which no intimate relationship could ever be recovered. Edgar mourns a young woman he courted for three years and was married to for fewer than one—he admits he has eagerly anticipated being buried beside her but now, because of perceived perils and foes, he (instead) fears abandoning their daughter.19

“Through winter nights and summer days [Cathy] was a living hope at my side. But I’ve been as happy musing myself among those stones, under that old church—lying, through the long June evenings, on the green mound of her mother’s grave, and wishing, yearning for the first time when I might lie beneath it.”

In what he believes to be the last days of his life, Edgar confesses that he wanders the churchyard, lying on his wife’s grave, yearning to be reunited with her.2021

‘Resign her to God…’

“Resign her to God—,” Nelly consoles Edgar, “and if we should lose you—which may He forbid—under His providence, I’ll stand her friend and counsellor to the last.”

Edgar Linton believes he may secure his daughter’s retention of Thrushcross Grange if she marries Linton Heathcliff, his sister’s son, the only legal heir. Edgar writes to his nephew and invites him to visit the Grange but Heathcliff forbids it; Edgar forbids his daughter from visiting the Heights. And so, riding and walking on common ground—the moors—is proposed by Linton Heathcliff.

Our next short chapter takes place in late-summer 1801…

‘An indefinite alteration…’

Cathy Linton has turned seventeen-years-old. It is a ‘close, sultry day, devoid of sunshine, but with a sky too dappled and hazy to threaten rain.’ Her father has allowed Nelly and Cathy to ride to the guide-stone, by the cross-roads.22

Upon their arrival they are told by a little herd-boy messenger, to travel further.

As has become increasingly the case, Heathcliff has manipulated the situation to lure Cathy closer to Wuthering Heights. By the time she and Nelly arrive to where Linton lay in the heath, they are a quarter mile from the Heights—three and half miles from the Grange.

He lay on the heath, awaiting our approach, and did not rise till we came within a few yards. Then he walked so feebly, and looked so pale…

Linton is so ill Cathy agrees to simply sit with him. Attempting to cheer him she is reminded of his heaven. “You recollect the two days we agreed to spend in the place and way each thought pleasantest?” she says, “This is nearly yours, only there are clouds; but then, they are so soft and mellow, it is nicer than sunshine. Next week, if you can, we’ll ride down to the Grange Park, and try mine.”

“An indefinite alteration had come over his whole person and manner,” explains Nelly, “The pettishness that might be caressed into fondness, had yielded to a listless apathy.”

“There was less of a peevish temper of a child which frets and teases on purpose to be soothed, and more of the self-absorbed moroseness of a confirmed invalid, repelling consolation, and ready to regard the good-humoured mirth of others as an insult.”

As is often the case in Wuthering Heights, the sense of violence and/or danger which readers associate with Heathcliff is exhibited in the actions or words of another. We do not experience Heathcliff’s abuse of Linton, but the sixteen-year-old’s behavior is evidence of an imperceptible danger.

After falling asleep, Linton wakes with a start. When Linton wakes he is agitated and afraid: “I thought I heard my father,” he gasps, glancing at ‘the frowning nab above [them]’ and asks, “You are sure nobody spoke?” A nab is a summit or high point of a rock formation—a cliff among the heath, perhaps?

Linton Heathcliff, we assume at this chapter’s end, has been told to secure a marriage to Catherine Linton. We can surmise Heathcliff has lost his patience with Linton and inflicted some sort of abuse on him—likely, psychological. What do you think?

As we move into the final chapter of our reading assignment, are you wondering why Nelly—who promised Edgar to be a friend and counsellor to the last to Cathy—does not encourage the young lady to be honest with her father? Should she not admit that Linton Heathcliff appears very unwell and his father is not abiding by the terms of the agreement, as they were forced to travel nearly all the way to the Heights rather than to the guide-stone within the boundaries of the Grange?

‘Just like the landscape—shadows and sunshine…’

August 1801—A Month Prior to Lockwood’s Arrival at Thrushcross Grange

Edgar Linton’s health is failing. Nelly tells Lockwood he ‘flattered himself’ with the idea her visits to her cousin, ‘would be a happy change of scene and society,’ and he, ‘drew comfort from the hope that she would not now be left entirely alone after his death.’

It is August and ‘every breath from the hills (is) so full of life.’ Nelly believes the fresh air could revive even those who are dying. Cathy, of course, is heartbroken. Imagine…her sole parent is dying. Her future includes a marriage to young (undesirable) Linton, who is also dying. And her only friend in the world is forty-five-year-old Ellen Dean.

Catherine’s face was just like the landscape—shadows and sunshine flitting over it, in rapid succession; but the shadows rested longer and the sunshine was more transient…

Brontë’s use of the sunshine and shadows is really brilliant here, isn’t it? Can’t we all imagine the sunshine expressed in a smile or a laugh or a twinkle in one’s eye versus the shadow of a furrowed brow, a frown or lowered eyes.

When she and Nelly come upon Linton he is animated, driven by absolute terror. He acquiesces, “I am a worthless, cowardly wretch—I can’t be scorned enough.” He tells her to save her hate for his father, and when she tells him to stand up and stop acting like, ‘an abject reptile,’ he becomes more agonized.

“I’m a traitor too,” Linton cries amidst his wailing, “and I dare not tell you!” When he adds, “…leave me and I shall be killed! Dear Catherine, my life is in your hands,” we must assume Heathcliff has threatened him in some way. Then, when he adds the additional statement, And perhaps you will consent,” we wonder, consent to what?

Cathy assumes he is asking her to stay—to put off returning to her father’s bedside. She asks him to divulge his secret—what is it that he ‘dare not tell?’ The scene is so chaotic and emotionally charged, when Heathcliff appears we’re partially relieved; now, at least, we may get some answers. Nelly describes Heathcliff’s arrival:

When hearing a rustle among the ling23 I looked up, and saw Mr. Heathcliff almost close upon us, descending the Heights. He didn’t cast a glance towards my companions, though they were sufficiently near for Linton’s sobs to be audible; but hailing me in the almost hearty tone he assumed to none besides, and the sincerity of which I couldn’t avoid doubting, he said—

“It is something to see you so near to my house, Nelly! How are you at the Grange? Let us hear! The rumour goes,” he added in a lower tone, “that Edgar Linton is on his death-bed—perhaps they exaggerate his illness?”

We must always keep in mind that Nelly is a foster-sister to Heathcliff, in much the same way she was to Hindley. And so, Nelly’s loyalties are always a bit skewed; she always empathized with Heathcliff and because of his quiet and gracious demeanor, she preferred caring for him to nursing Hindley or Catherine. When he addresses her she detects sincerity in his voice. And upon hearing Edgar is dying, he quite honestly, confesses to hoping Edgar dies before Linton. He does it such a way it barely rattles the housekeeper. When Heathcliff begins to berate Linton, instructing the half-dead teenager to, ‘get up,’ his son pants, “I will, father! Only, let me alone, or I shall faint! I’ve done as you wished…”

What exactly has Heathcliff wished?

“I can never re-enter that house, I am not to re-enter it without you!” Linton cries.

Now, Heathcliff’s deception becomes clear, doesn’t it? Linton was supposed to entice his cousin Cathy to accompany him back to Wuthering Heights. Cathy arrived already agitated, desiring to return to her father and the Grange. How does Heathcliff get her into the Heights? Perceived acts of violence.

“Stop,” he shouts, silencing Linton. Kindly, he continues, “We’ll respect Catherine’s filial scruples.” Heathcliff pretends to placate Nelly, surrendering to her concern Linton should be under the care of a doctor: “Take him in, and follow your advice concerning the doctor, without delay.”

Her concern for Linton, not surprisingly, is not strong enough for her to be deceived. Remember, Nelly knows Heathcliff. She replies, stiffly: “To mind your son is not my business.” This is when Nelly tells Lockwood (my italics): Heathcliff approaches his son, and makes, as if he will, ‘seize the fragile being.’

‘I’ll burn that door down, but I’ll get out.’

Using a perceived threat of executing acts of violence, Heathcliff ushers Linton, Cathy and Nelly inside his house at Wuthering Heights. He suggests the women stay for tea and informs them Joseph and Zillah are, ‘off on a journey of pleasure,’ and Hareton has taken ‘some cattle to the Lees.’ He closes the door and locks it. Four are locked in, and three are locked out.

“…Though I’m used to being alone,” he tells them, “I’d rather have some interesting company, if I can get it.” Addressing Cathy, he insists, “Miss Linton, take your seat by him.” And then, he apologizes for having only Linton to offer—recognizing, she is certainly deserving of a higher quality suitor. It’s what he says to the teenagers next that has been analyzed by critics for decades:

“How she does stare! It’s odd what a savage feeling I have to anything that seems afraid of me! Had I been born where laws are less strict, and tastes less dainty, I should treat myself to a slow vivisection of those two, as an evening’s amusement.”

I’m curious…what did you think about this statement? It’s oftentimes referenced in discussions of Heathcliff being a beast (or ghoul), rather than, a man. Vivisection, for those who do not know, is dissection of a living organism (I repeat: living organism) for physiological or pathological investigation. Emily Brontë knew, the only species performing vivisection in the Victorian age were: men.24

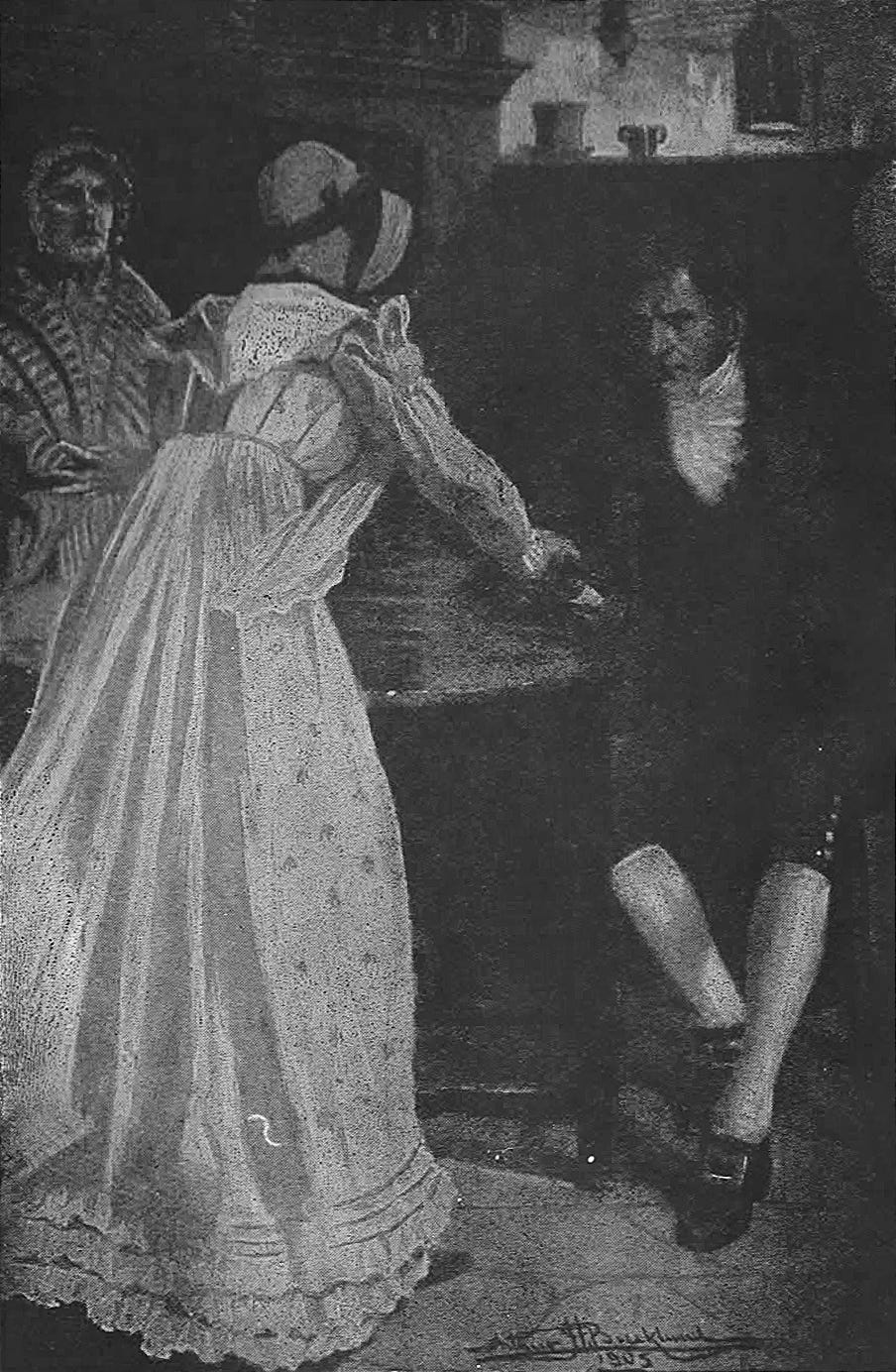

Heathcliff is using words (again) to inflict terror. What could possibly sound more horrifying than someone suggesting he wishes to dissect you? When he swears to himself, “By hell! I hate them,” Cathy resists any perceived threat:

“I’m not afraid of you!” she exclaims. Rather than shrink back from him, she steps closer. “Give me that key—I will have it!” she demands, ‘her black eyes flashing with passion and resolution.’ Heathcliff was holding the key in his hand, which remained on the table. Nelly tells Lockwood he ‘seized with a sort of surprise at her boldness,’ or, perhaps it was not her boldness, his foster-sister recognized, but instead, ‘her voice and glance,’ which likely reminded him of her mother, Catherine. Brontë hints he is disarmed, lost in his memories, when she tells us Cathy nearly retrieves the key from his ‘loosened fingers.’

When he is shaken from his thoughts of Catherine, Edgar Linton’s seventeen-year-old, yellow-haired daughter is still snatching at the key. He attempts another threat, “Now Catherine Linton,” he says, using her surname, “stand off, or I shall knock you down; and that will make Mrs. Dean mad.”

I wonder, is he suggesting, he does not wish to upset Nelly? Heathcliff acts out when he is provoked, he believes he provides victims with fair warning (threats) to avoid his wrath.25 He is accustomed to everyone mistrusting him; since he was brought to the Heights he has been scorned, treated like an animal (left to sleep on a landing, told he should be put ‘in the cellar.’). Eventually, he developed ‘iron muscles,’ and he gained the bulk to inflict fear. Most of the time he need use only words to prevent violence. When Cathy defies him, digging her nails into his flesh26 and biting him, he sheds his sullen, patient, formerly ‘uncomplaining-as-a-lamb’ nature;27 he grabs the seventeen-year-old and violently slaps her, boxing her ears.28

Nelly saw the change in his face, the calculation of his intended violence and she did nothing to prevent it. She is not familiar with unhinged Heathcliff; she knows only a young man who threw applesauce and kicked a chair.

If Catherine were alive, she could have prevented it.29

Nelly cries only, “You villain! you villain!” and The Villain brews tea for his captives.

It’s difficult for us (in contemporary times) to imagine such behavior, isn’t it? Today, this behavior would be cause for authorities to be called, orders of protection from abuse, countless child welfare organizations to get involved, charges of kidnapping and detention, etc.. Unfortunately, in rural Victorian England (and in America), this sort of thing might go largely unnoticed.

“Wash away your spleen,”30 says Heathcliff to Nelly, “And help your own naughty pet and mine. It’s not poisoned, though I prepared it. I’m going out to seek your horses.”

In Heathcliff’s absence Nelly and Cathy learn the purpose of their imprisonment: Linton and Cathy are to be married the following morning.

Linton, pleased with himself for achieving the deception, tells the women they are to remain at the Heights all night and after the two are married, Cathy is to return home to the Grange, taking Linton with her. Cathy is livid, threatening: “Stay all night? No! Ellen, I’ll burn that door down, but I’ll get out.”31

‘Oh, you are not afraid of me…you seem damnably afraid!’

Catherine Linton attempts to appeal to Linton’s humanity in the final episodes of the chapter,32 but he is happy to steal away to his chamber, leaving Cathy and Nelly alone with Heathcliff.

Cathy shrinks from Heathcliff when he approaches the hearth, where she is seated. Thinking back to the earlier scene, he mocks: “Oh, you are not afraid of me? Your courage is well disguised—you seem damnably afraid!” She confesses that now, she is afraid; that, all she wishes to do is return to her father. She tells him her father wishes her to marry Linton, but her absence overnight will make him miserable. Of course, causing Edgar distress is Heathcliff’s favorite pastime, so he is happy to oblige. When Cathy attempts to convince her uncle to send Nelly back to Edgar, so he might know they are both safe, Heathcliff is further agitated; his Catherine would put Heathcliff before her husband but young Cathy will not put him before her father.33 Heathcliff becomes especially cruel:

“Catherine, his happiest days were over when your days began. He cursed you, I dare say, for coming into the world (I did, at least). And it would just do if he cursed you as he went out of it. I’d join him. I don’t love you! How should I?”

Brontë sometimes equates Catherine’s death with childbirth, rather than fasting for weeks.34 Heathcliff blames Cathy, not for complications suffered at childbirth, but instead, the younger Cathy is the living, breathing evidence of Edgar and Catherine Earnshaw’s union.

Unfazed by Heathcliff’s verbal abuse, Cathy—extending the Linton’s trademark grace and forgiveness, appeals to her uncle’s human nature.

“Mr. Heathcliff, you’re a cruel man, but you’re not a fiend;” she observes, “and you won’t, from mere malice, destroy, irrevocably, all my happiness.” She demands he make and keep eye contact with her.35 Cathy’s kindness and sensitivity repels him. When, finally, she asks, “Have you never loved anybody, in all your life, uncle?” he has enough:

“Keep your eft’s fingers off;36 and move, or I’ll kick you! I’d rather be hugged by a snake,” he declares, “How the devil can you dream of fawning on me? I detest you!”

‘I thought Heathcliff himself less guilty than I’

Our reading assignment ends this week on a rather dismal note—Catherine Linton and Ellen Dean are imprisoned overnight at Wuthering Heights.

Nelly partially blames herself, owing to her ‘many derelictions of duty,’ which have brought, ‘all the misfortunes of all [her] employers.’ What do you think? Has Nelly any part in the misfortunes of Mr. Earnshaw, Hindley Earnshaw or Edgar Linton?

At seven o’clock on an August morning in 1801, Heathcliff retrieves Catherine Linton from her overnight accommodations in Zillah’s chamber. Ellen Dean, unfortunately, is forced to remain. Five nights and four days, altogether…‘seeing nobody but Hareton.’

What’s Next?

Next week’s assignment includes four chapters: (V2: Chapters 14-17, or 28-31).37

Rumors swirl around Black Horse Marsh. Linton embraces his bad-nature. Doctors are called, lawyers are fetched. Heathcliff returns to the Grange, again beneath the Harvest Moon. Graves are disturbed, ghosts may walk and Lockwood settles his bill.

We’re almost finished reading Wuthering Heights…love it? hate it? utterly surprised?

Support my writing and research: Buy Me a Book | Buy Yourself a Book

Johnson, Ben. “Michaelmas.” Historic UK, 2021

The four recognized quarter days are: Lady Day (25 March) • Midsummer (24 June) • Michaelmas (29 September) • Christmas (25 December). Ed. Alexandra Lewis notes: “Tenancy of houses begins and ends on these days.”

Cathy is wiping tears from her cheeks.

Volume 1: Chapter 11

Who, remember, has been raised by Heathcliff.

Volume 1: Chapter 9

Compare with Catherine Earnshaw, “a wild, wick-slip” of a girl. A slip is a cutting of a plant, used in propagating or grafting; in other words, a piece taken from a parent plant. Is Brontë making the point he is from the genetically weaker Linton line?

Volume 1: Chapter 5

Just guessing, as I have no experience being tortured in 16th/17th c England.

Nelly continues to remind us of her role as an unreliable narrator, does she not?

Volume 1: Chapter 4

This is Hareton Earnshaw’s “Tureen of Hot Applesauce” moment.

Volume 1: Chapter 3

Joseph wishes for Hareton to supplant Linton but encourages Linton to act like Heathcliff.

And, Hareton (again) is diminished due to his social class, rather than simply unmannerly behavior.

Volume 2: Chapter 11 (25)

my italics

Volume 2: Chapter 15 (29)

Compare with Nelly’s fear in Volume 1: Chapter 11: “I fear that God had forsaken the stray sheep there to its own wicked wanderings, and an evil beast prowled between it and the fold, waiting his time to spring and destroy.”

Compare with Isabella’s statement to Heathcliff in Volume 2: Chapter 3 (17): “Heathcliff, if I were you, I’d go stretch myself over her grave and die like a faithful dog.”

Compare to Heathcliff’s (future reading assignment) confession to Nelly in Volume 2: 15 (29).

This is where Nelly saw an, ‘elf-locked, brown-eyed boy’ (Hareton). It’s also where Heathcliff believed Hindley should have been buried, as the folk belief recognizes one who commits suicide (in Hindley’s case, by alcoholism) is to be buried at the crossroads rather than in a sacred churchyard.

ling: heather (Calluna vulgaris); Nelly refers to the heather (or heath) as ling, referencing the word derived from the Anglo-Saxon, lig or, fire. Historically C. vulgaris was used as fuel.

“There was significant opposition to vivisection in England in both houses of Parliament during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901). The Queen herself was strongly opposed to it as were writers George Bernard Shaw and Mark Twain (Animal Free Science Advocacy).”

The Hot Applesauce Incident of 1777 (against Edgar) was provoked by shame and adolescent rivalry; The Hanging of Fanny was provoked by the immediate necessity to quiet a barking dog; and The Beating of Hindley was provoked by a brazen attempt on his life.

The Dinner Knife Throwing Incident was Heathcliff’s attempt to halt Isabella and scare her into submission—she escaped, and he made no further effort to pursue her.

Similarly to when Isabella tried to free herself from Catherine’s grip.

Volume 1: Chapter 4

In the Victorian era, “boxing of the ears,’ was a familiar punishment in child-rearing (discipline) and, within the military. It can cause ear drum damage and hearing loss.

Heathcliff would never harm Cathy, as he did not harm Edgar. His submissiveness to Catherine prevented injury to anyone she may hold in esteem.

spleen: bad temper (The Annotated Wuthering Heights, 2014, Gerazi, J.)

Extra points go to Ellen Dean for utilizing, ‘pitiful changeling,’ ‘little perishing monkey,’ and ‘puling tricks,’ in her tirade against Linton.

Volume 2: Chapter 27

And she certainly does not elevate Linton above her father!

Catherine Earnshaw refused food, resulting in malnutrition and death.

Interestingly, in the animal kingdom, eye contact is often a sign of aggression or represents a potential threat. If Heathcliff is more beast than man, perhaps this ‘extra-animal’ gesture Cathy believes will warm him to her is actually perceived as a threat.

See the little fingers on that newt (pictured above)? The eft is the juvenile stage of a newt.

Have you seen my new Chapter Conversion Chart?

Hey 👋🏻 I've finished the book! Also, saw this and thought of you https://www.instagram.com/p/DJV4hIZsRNQ