Welcome to Week Four of our Wuthering Heights read-along…

This week’s assignment is Volume I: Chapters XI through XIV (11-14).

What Happens in Chapters XI-XIV?

Nelly is reunited with Hareton. Heathcliff continues to visit the Grange. Edgar and Heathcliff quarrel and Catherine takes to her room. Isabella hastily marries and she immediately regrets it. And once again, the housekeeper is tasked with an unsettling responsibility.

‘An elf-locked, brown-eyed boy…’

January 1784

Do you remember last week—when I promised I’d keep my summary essay short and then miserably failed? It happened again this week. Fortunately, I’ve already written an essay about Nelly and her remembrance of her childhood with Hindley.

Read: “An Elf-locked, Brown-Eyed Boy: Silvery Vapor and Superstition”1

What did you think about Nelly’s reunion with young Hareton? In this chapter, he is about five or six-years-old; he’s been raised in the care of Hindley and Joseph (he now also lives in the presence of nineteen-year-old Heathcliff, who encourages him to call his father, ‘devil daddy’).

Keep in mind…we know from Chapter II, that in 1801, at age twenty-three, Hareton remains at the Heights, still residing with Heathcliff and vinegar-faced Joseph.

‘I’ll try to break their hearts, by breaking my own.’

January 1784—Plough Monday

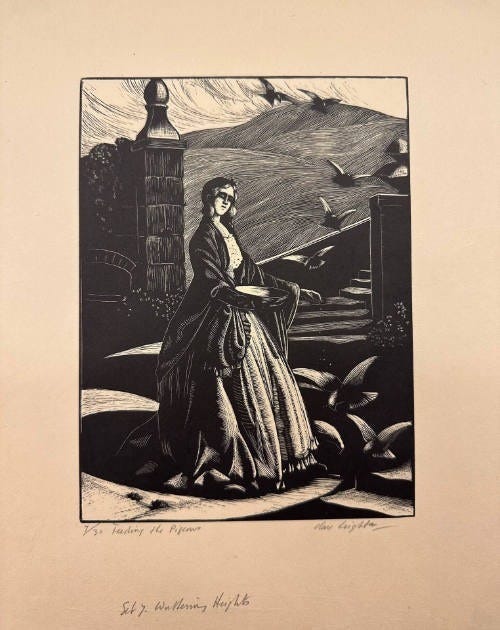

After Nelly’s incident with Hareton; Heathcliff arrives at the Grange, and Catherine is occupied feeding some pigeons. Artist Clare Leighton made a lovely woodcut etching of this scene…

In it, Catherine is alone. That’s likely because she has not spoken to her sister-in-law in three days, not since the incident with Heathcliff. And, her relationship with Edgar is, shall we say, strained. Leighton’s woodcut depicts Catherine surrounded by pigeons in the courtyard at the Grange.

I’ve written about pigeons (and rural superstitions related to pigeon feathers) in a previous essay called, “The Down is Flying About Like Snow.” The essay includes spoilers; unless you’re rereading the novel, or ahead in the reading schedule, wait until you finish next week’s assignment to visit the link.

When Nelly describes the scene—Catherine quietly feeding the pigeons—she explains to Lockwood that before the recent altercation between Cathy and Isabella, Heathcliff never bestowed ‘a single unnecessary civility on Miss Linton,’ but on this particular day, he is all charm. When Nelly, observing from a kitchen window, sees him embrace Isabella, she cries out, “Judas! Traitor!” Discovering she is not alone in the kitchen, she must divulge to Catherine what she’s witnessed—Catherine confronts Heathcliff.

Did you notice: Catherine is not angry that Heathcliff kissed Isabella? She is more so angry that his action will result in his banishment from visiting the Grange. Also, she asks, “Did she come across you on purpose?,” placing immediate blame on Isabella.

Reminder: Isabella and Catherine are eighteen, Heathcliff is nineteen.

If Catherine had not reacted so absurdly to Isabella showing interest in him, incurious Heathcliff would never have given her any of his attention. Catherine greedily claimed she will—to fix Isabella—have ‘half a dozen’ sons with Edgar Linton—exhibiting her covetousness of his ‘goods.’ Yet, this morning, she questions Heathcliff’s motives?

“What is it to you?” [Heathcliff growls]. “I have a right to kiss her, if she chooses, and you have no right to object. I’m not your husband: you needn’t be jealous of me!”

This is not the lovesick Heathcliff we are accustomed to, is it? He lashes out (growls) at his beloved Catherine and makes it very clear: he is not her husband. Brontë makes clear that Heathcliff’s embrace was of Isabella’s choosing—he did not force himself on the girl; remember: he is repulsed by her. However, to achieve revenge on Edgar (and Cathy!), Heathcliff must do what he must do; if kissing Isabella is a means to the end, he will pursue her.

This passage requires a bit of mulling…

Remember, Heathcliff after hearing Catherine say it would degrade her to marry him, rushed from the Earnshaw’s kitchen and remained absent for three years. He does not know she told Nelly she intended to marry Edgar to ‘aid Heathcliff to rise, and place him out of [Hindley’s] power.’ Heathcliff spent three years rising. Without Catherine. And, the nineteen-year-old now is certainly not under the power of Hindley.

When he enlightens her to his opinion of her union with Edgar (she has ‘treated him infernally’), Catherine labels him, ‘ungrateful brute,’ and asks, “What new phase of his character is this?”

Three days ago—during her tantrum—Catherine provoked this change in Heathcliff.

Their exchange is informative, is it not? Heathcliff calls Catherine a tyrant—did you notice this? He likens her to a slave master. Enslaved by his love for her, Heathcliff tells her, “You are welcome to torture me to death for your amusement, only allow me to amuse myself a little in the same style.” Clarifying he knows Catherine’s true feelings, he declares, “If I imagined you really wished me to marry Isabella, I’d cut my throat!”

This is SUCH a powerful scene—Catherine eventually cries, “Quarrel with Edgar, if you please, Heathcliff, and deceive his sister; you’ll hit on exactly the most efficient method of revenging yourself on me.” And their conversation ceases…

When this scene resumes, Nelly has informed Edgar of Heathcliff’s presence and the quarrel which had commenced between he and Catherine. Isn’t it interesting: Edgar initially blames his wife for entertaining, ‘the low ruffian?’

Over the next four-and-a-half pages Heathcliff is characterized as a violent beast. Did you notice, though, when Nelly encourages Edgar to interrupt his wife and her guest:

Mrs. Linton…was scolding with renewed vigour; Heathcliff had moved to the window, and hung his head, somewhat cowed by her violent rating apparently.

Emily Brontë gives readers brief glimpses into the submissive behavior of Heathcliff, tucked ever-so-neatly between major episodes. I recognize why critics despise this story after one quick reading—and staunchly maintain: Heathcliff is a monster.

Heathcliff was raised in the volatile, violent environment of the Heights—he mirrors those who created him. It is only to please Catherine, Heathcliff is provoked to behave like the Earnshaws—and especially like, Hindley.

When Edgar directs his animosity for Heathcliff toward Catherine, the die is cast.

Until I listened to an audiobook narration of this scene, I did not grasp how powerful Edgar’s dressing down of Catherine really is; Brontë (again) brilliantly illustrates for us, emotion and passion in the speech of one who is wounded. Edgar, the gentry, is utterly horrified by his wife’s affection for someone he considers little more than the plough-boy. He is disgusted by everything about Heathcliff—posh clothes, improved diction, none of it matters. “You are habituated to his baseness,” Edgar tells his wife, provoking her only to react with: ‘carelessness and contempt of his irritation.’

Again, I’m thinking back to Catherine’s proclamation: I am Heathcliff.

Heathcliff purposefully draws Edgar’s angry attention away from Cathy. Edgar lowers his voice and tactfully explains his position.; he politely describes the mere presence of Heathcliff, ‘a moral poison that would contaminate the most virtuous.’

Finally, he declares Heathcliff is no longer welcome at the Grange and he gives him an ultimatum of three minutes to exit the premises.

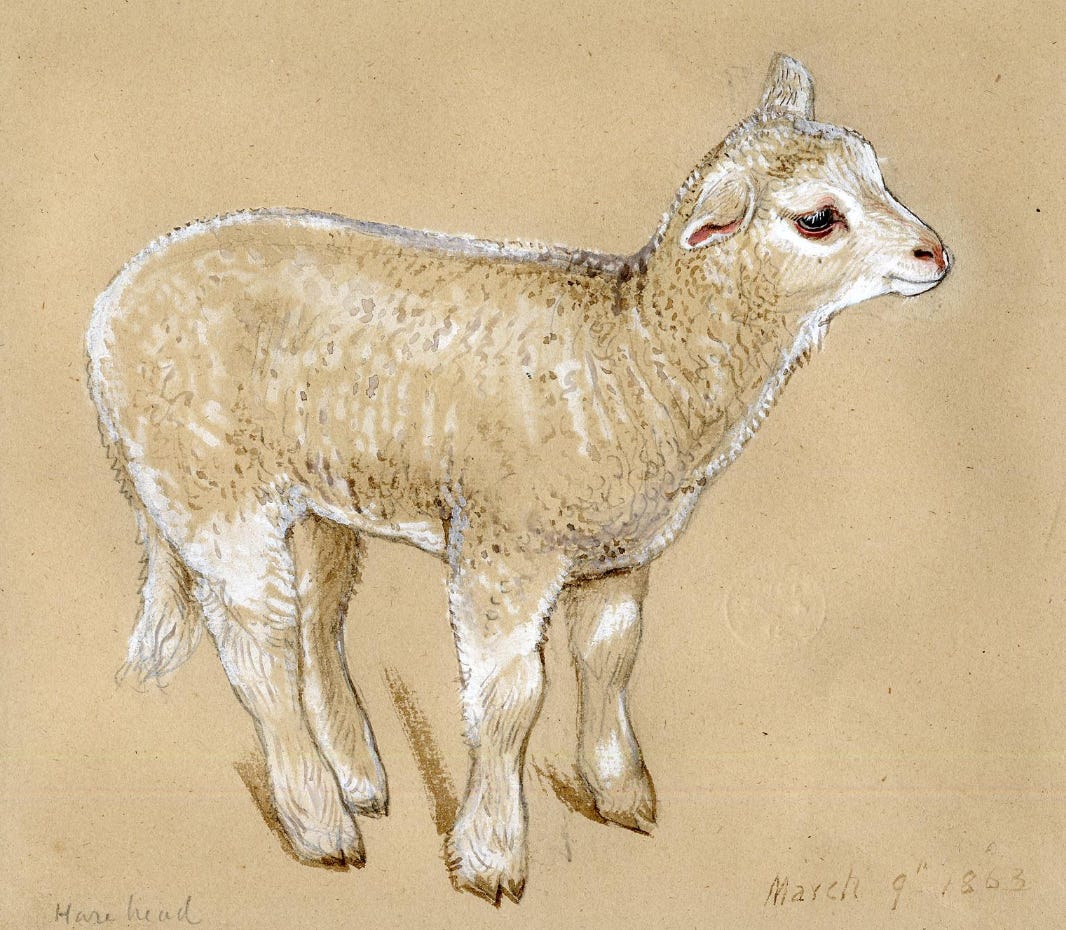

After measuring the height and breadth of Edgar, ‘with an eye of derision,’ Heathcliff mocks: “Cathy, this lamb of yours threatens like a bull!” He then taunts, Edgar is not worth striking. When Edgar hints to Nelly to fetch the aid of others, Catherine locks the door and commences a tirade against both men. Edgar crumbles. Brontë (through Catherine) now identifies him as weaker than a lamb; his wife characterizes him as no more than a ‘sucking leveret.’ A leveret is a young hare—cowardly and frail.

“I compliment you on your taste,” says arrogant Heathcliff to Catherine, sarcastically observing, “and that is the slavering, shivering thing you preferred to me!”

What happens next is a surprise, is it not?

Nelly tells Lockwood, after Heathcliff gives Edgar’s chair a degrading push, Cathy’s ‘sucking leveret,’ springs to his feet and strikes Heathcliff, ‘full on the throat a blow that would have levelled a slighter man.’

Edgar Linton has finally had enough!

This is a hugely pivotal scene—as I’m sure you discovered—and we learn during its aftermath, Catherine would rather Heathcliff flee (“I’d rather see Edgar at bay than you.”) than remain and have to defend himself against Edgar and half-a-dozen men.

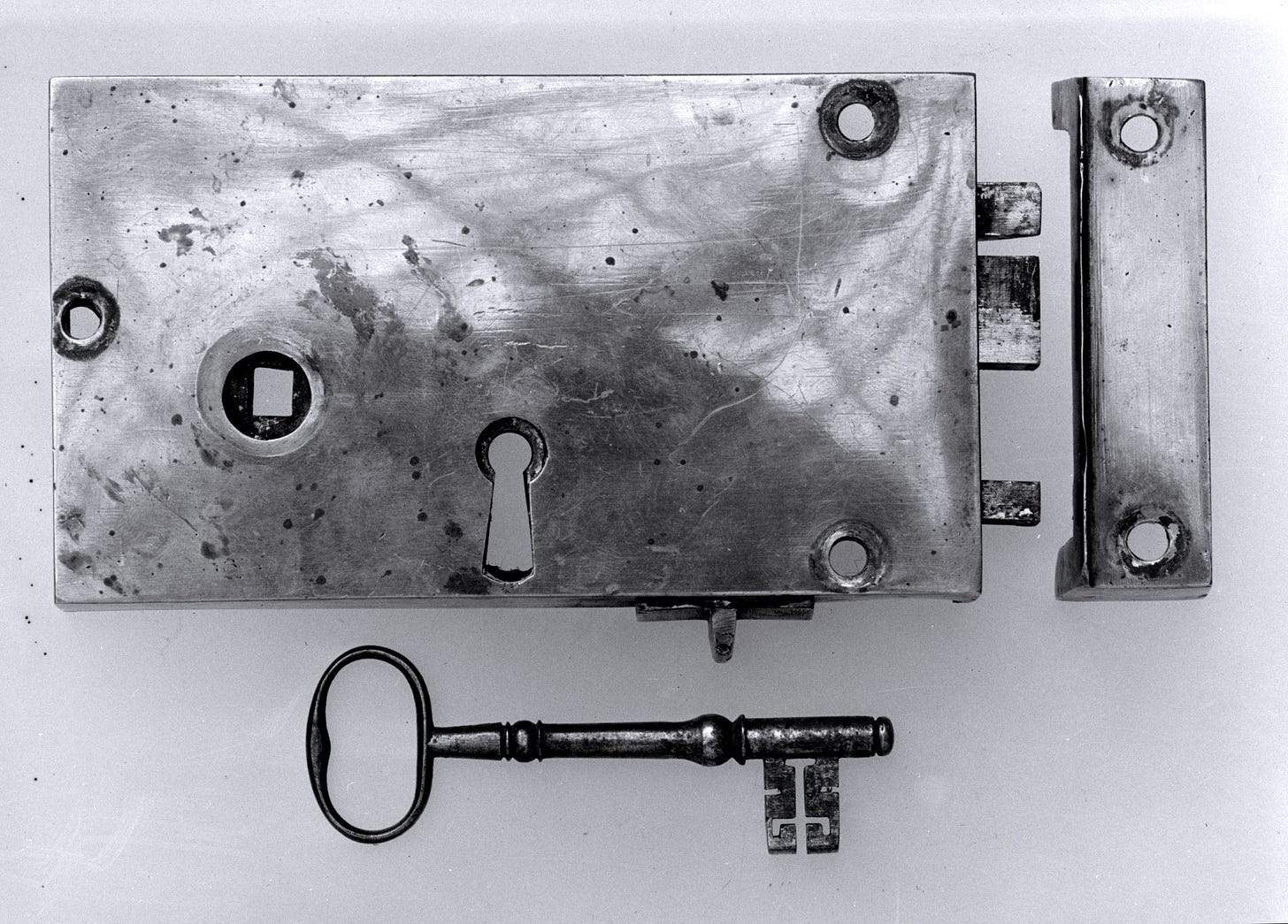

Using a poker to smash the lock from the inner kitchen door, Heathcliff escapes…

Who does Catherine blame for this uproar? Isabella. Cathy is aligned with Heathcliff in heart and soul, she certainly will not blame him (for that kick to Edgar’s chair) and, she is aligned in matrimony & material things with Edgar, so she will not blame him (for a choking blow to Heathcliff’s throat). Of course, it must be Isabella’s fault!

In the final pages of Chapter XI we see Catherine threaten to break the hearts of both men—by breaking her own. When Edgar returns and asks if she is willing to give up her relationship with Heathcliff she becomes ‘wild,’ reminding him of her passionate temper, which she describes as, ‘verging, when kindled, on frenzy.’

Wuthering Heights is commonly thought of as “romantic,” says author Jeanette Winterson, but try rereading it without being astonished by the extremes of physical and psychological violence.

What did you think of Catherine, ‘dashing her head against the arm of the sofa, and grinding her teeth?’ Nelly—like a mother accustomed to a toddler’s tantrums—offers Edgar advice on how to manage his wife. Catherine eventually rushes from the parlour and locks herself in her room. And that is where she remains for three days…

In the essay linked above, “The Down is Flying About Like Snow,” I discuss the episode during which Catherine experiences delirium and I illuminate many of the rural/rustic superstitions related to feathers, mirrors and windows.

Catherine’s delirium also provides us with glimpses into her childhood spent with Heathcliff, of their shared macabre nature and her desire to be with him, always.

If you read my essay, please leave a comment…let’s chat about it! (Remember: spoilers!)

Since I’ve already written a long form essay about the scene in which Catherine tears at her pillow, plucking out feathers and reminiscing about her lost youth, I’ll tease out other interesting themes from this chapter: books, windows and psychosomatic illness.

‘He is continually among his books…’

January 1784—Friday

Before Catherine increases ‘her feverishness bewilderment to madness,’ she inquires as to Edgar’s condition; Nelly foolishly replies with blunt fact: “He’s tolerably well, I think, though his studies occupy him rather more than they ought; he is continually among his books, since he has no other society.”

“Among his books! And I dying!” cries Catherine in disgust. She is entirely mortified that her husband is seemingly indifferent to her, in fact, she is so angry she asks Nelly to ‘frighten’ him with threats of a hunger strike and starvation.

Nelly is apathetic and so, her mistress is incensed! Catherine accuses every member of the household of caring not if she dies. Edgar, she believes, will be pleased and say, “thanks to God for restoring peace to his house, and [go] back to his books! What in the name of all that feels,” she asks, “has he to do with books, when I am dying?”

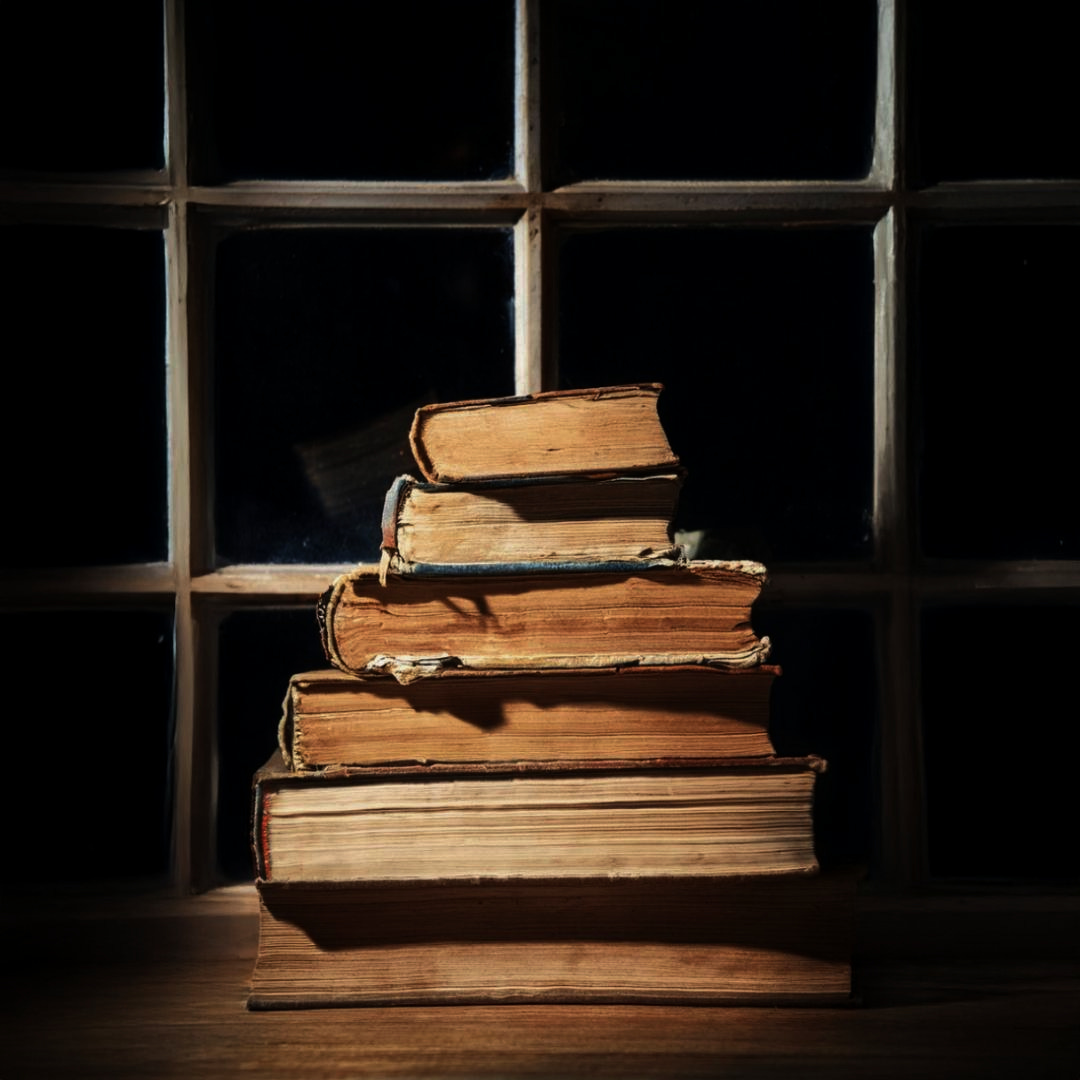

Let’s talk about books…

Emily Jane Brontë (in fact, all of the Brontës) loved books! Her novel is filled with books. In the first few chapters of the novel (Chapter II) Cathy Linton—puts a fright into Joseph: ‘she takes a long, dark book from a shelf,’ and pretends it is a book of witchcraft—of course, it is not.

In Chapter III, young Cathy is reprimanded by Heathcliff when he discovers her idly sitting, reading—“Put your trash away,” he tells her.

The evening before that scene, Mr. Lockwood piled ‘a few mildewed books’ into a magical pyramid to defend against a supernatural spectre!

What’s going on here—what do all these books represent?

Books represent knowledge. In the first few chapters of the novel we are introduced to books in a number of ways. Heathcliff’s daughter-in-law, is reading for pleasure. The long, dark book from a shelf was unfamiliar to Joseph, so we know it is not the Bible or any text affiliated with the church. And, what about the pile of mildewed books?

In a previous essay, “Conjuring Up Ghosts,”2 I discuss city-dweller Lockwood’s use of books to repel what he considers (uneducated) rustic superstition; he piles Catherine Earnshaw’s books (e.g. intellect, knowledge) in the shape of a magic pyramid to repel her ‘ghost.’

Do you remember when the little Earnshaws and the little Lintons were all educated by the curate? And Hindley was sent off to college? Education was valued. After Mr. Earnshaw died, Hindley returned as master of the Heights; and you likely remember, he deprived Heathcliff, ‘of the instructions of the curate’…yet, the children still valued education and ‘Cathy taught him what she learnt.’ Catherine shared her education with Heathcliff.

By 1801—Heathcliff becomes opposed to the idea of sitting idly and reading a book. We’ll see—as the story unfolds—how Emily Brontë uses books (e.g. literacy) to create distinctions among social classes.

‘Open the window again wide, fasten it open!’

When I introduced Symbolism & Structure on Substack I invited readers to suggest themes they would like to see me discuss in my essays.

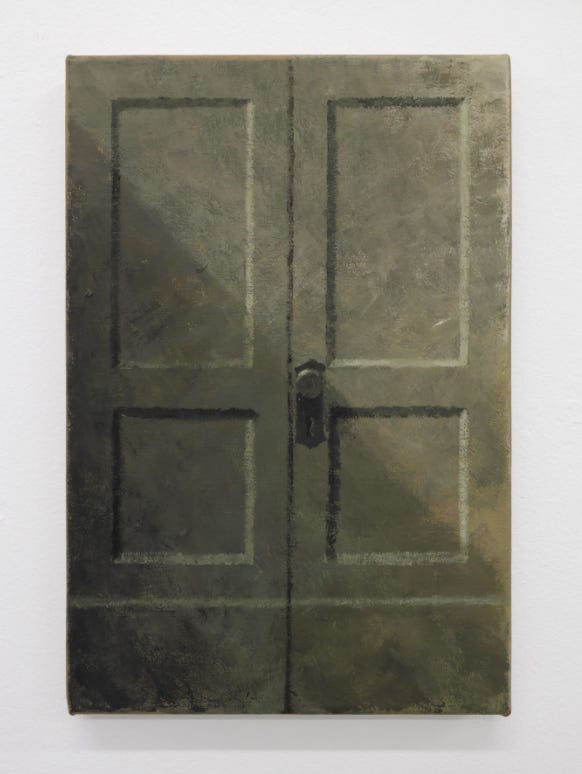

commented:I am fascinated in the food and furniture, doorways at Wuthering Heights...

Me too, Sharon! And so, I thought this week’s assignment is a good place to discuss the windows (and doors) of Wuthering Heights. I’m also going to include gates in this discussion—anything desired for human ingress and egress!

Let’s rewind a bit—to the first page of the novel—when city dweller and southerner, Mr. Lockwood, appears at the Heights. He is met by his landlord Heathcliff, whose ‘black eyes withdraw—suspiciously under their brows,’ and who utters a less than inviting: “Walk in!”

Even the gate over which he leant manifested no sympathizing movement to the words…when he saw my horse’s breast fairly pushing the barrier, he did pull out his hand to unchain it, and then sullenly preceded me up the causeway…

Do you remember how you felt as you read this passage? Immediately, Brontë placed us in the same awkward situation Lockwood found himself in—an unwelcome guest in unwelcoming country. As we anxiously ‘walk in’ alongside Mr. Lockwood we pass through the principal door, ‘above which, among a wilderness of crumbling griffins and shameless little boys;’ we detect the date 1500 and a name, Hareton Earnshaw.

Lockwood remarks, in his retelling of the incident, Heathcliff’s attitude appeared to demand either ‘speedy entrance’ or ‘complete departure.’ This is a familiar feeling, I think, throughout the entire novel. We are never entirely comfortable being in this place—among these people. Brontë draws us deeper into the story—passing through thresholds, room after room, peeking in windows, gazing out windows.

In our Week One assignment (Chapters I-III), Lockwood was begrudgingly invited inside the Heights. Detained there by a snowstorm he is given two choices: leave unaccompanied and likely become lost and die from exposure somewhere on the moors or remain inside the unwelcoming house; he remains. The ‘stout housewife’ Zillah takes him to Catherine Earnshaw’s bedroom where Catherine slept with her foster brother, Heathcliff. Lockwood discovers a sort of large oak cabinet; one must pass through it sliding doors to crawl inside.

Once inside, he finds a window—which leads to the outside!3

This very subject is why I once confessed I could write about every single word in this novel. And, this is the reason why I cannot seem to limit the length of these summary essays each week! Emily Brontë created a meticulously layered narrative— characters’ interactions with walls, fences, gates, doors, and windows are filled with symbolism, I am obsessed with her ability to weave meaning into banal architectural elements and utilitarian items.

Returning to this week’s reading assignment…

In Chapter X (last week), Heathcliff had his fingers on a latch, wishing to gain entry to the Grange. Edgar graciously invited him inside. We are reminded of vampire lore.

Latches and locks dominate our attention in this week’s assignment, Heathcliff has become a returning visitor: Edgar exits through one door, Heathcliff escapes out the opposite. The Owner (of the Grange) is afforded effortless egress; the Other (from the Heights) must use violence to escape.

At the Heights, Heathcliff has latitude. When Nelly Dean follows little Hareton back to the farmhouse, the child effortlessly passes from the outside through its door and inside to its shelter. Heathcliff materializes and meets Nelly outside on the doorstones—he is part of the landscape; to gain entry to the interior spaces of the building, you pass through him.

In these last few reading assignments we are provided with wonderful examples of windows as liminal spaces. Heathcliff returns and visits the Grange. He waits outside in the shadows—again, part of the landscape—peering up into darkened (closed up) windows. Inside the dark house, Edgar and Catherine are gazing out an open window. Heathcliff is still wild and free, pursuing his youthful desire. Married now, Catherine has been domesticated, she is captive in the role of wife and mistress of the house.

In Chapter XII Catherine imagines she is in her box bed again at the Heights, and what does she desire most? To escape out of doors, for the window to be open…

Oh, I’m burning! I wish I were out of doors—I wish I were a girl again, half savage, and hardy, and free; and laughing at injuries, not maddening under them! Why am I so changed? why does my blood rush into a hell of tumult at a few words? I’m sure I should be myself were I once among the heather on those hills. Open the window again wide, fasten it open! Quick, why don’t you move?

As you know, I spend most of my time thinking about Heathcliff; he reminds me of a wandering soul, he is always between life-and-death. Heathcliff spends all of his time in doorways, leaving and entering, passing by or walking through, lifting latches, closing gates.

In a future chapter we’ll see him unloose the constraints of death and burial.

Can you think of some other examples of using gates, doors and windows…latches and locks, to represent characters’ social status, emotions, personalities, etc.?

‘My narrow home out yonder…’

January 1784

At the beginning of this week’s assignment, Catherine has refused to come out of her chamber for three days. She had refused food and only when she requires water in her pitcher to be replenished, does she unbar her door. She claims she is dying.

In Wuthering Heights, Catherine becomes ill because of a discrepancy between her inner and outer realities: living outside of societal norms with Heathcliff versus living well within society’s bounds with Edgar, but separated from Heathcliff.4

Do you remember when Edgar demands that Catherine choose—“Will you give up Heathcliff hereafter, or will you give up me? It is impossible for you to be my friend and his at the same time; and I absolutely require to know which you choose?”

This ultimatum causes Cathy’s second Heathcliff-related illness. The first, being her breakdown after his departure in the thunderstorm (Chapter IX). Marrying Edgar, in Heathcliff’s absence, Catherine denies her very nature—rather than remaining ‘half-savage, and hardy, and free’…she quite literally, settles down.

When Heathcliff returns, so does Catherine’s spirit. She is awakened. Unfortunately, she is married to another man. No matter. Catherine believes she should possess both men—her beloved soul mate, Heathcliff and her lawful husband, Edgar. If Isabella had not confessed to wanting Heathcliff for herself, and Catherine had not acted out in such a ridiculously possessive manner, causing such a scene, Edgar might never have noticed how detrimental Heathcliff’s visits to Thrushcross Grange had become.

When the two men quarrel and Edgar assaults Heathcliff, he might as well have struck Catherine. Catherine is Heathcliff. She blames Isabella; her soul-mate would not have pursued the young woman if he’d not been provoked to seek revenge against Edgar. It is only after Edgar harms Heathcliff, Catherine decides she has no choice but to break both their hearts.

Breaking Edgar’s is effortless; but breaking Heathcliff’s requires breaking her own.

Scholars have debated Catherine’s second illness for decades. In Victorian literature, a common illness assigned to female characters is hysteria (brain fever). Delirium is also common. Catherine Linton suffers from both of these; limiting her food weakens her body (and soul) further—until she becomes malnourished and incapable of thriving.

Remember, Heathcliff returned during the full Harvest Moon. During her self-induced illness, Catherine hallucinates under a new moon. The nights are now dark and Cathy has requested Nelly open her window. When Nelly refuses, saying, “I won’t give you your death of cold,” Cathy uses her ‘delirious strength’ to jump out of bed, cross her bedroom and throw open the window.

“You won’t give me a chance of life, you mean,” she says, reminding us Catherine’s heaven is found at Wuthering Heights. Outside her window, heaven awaits. She will be free again if she is simply permitted to die—her heaven is in ‘the middle of the heath on the top of Wuthering Heights.’ She is now, not only legally separated from a union with Heathcliff but Heathcliff is now physically barred from visiting the Grange. They have again been separated.

She has no reason to live; but if he—Heathcliff—remains, she ‘will still continue to be.’

When Edgar is summoned, his wife is no longer in any mood to negotiate. She makes it clear to him, she intends to will herself to death. She describes her ‘narrow home,’ her grave, ‘out yonder,’ ‘[her] resting place where [she is] bound before spring is over!’ And then she tells him she has no desire to be buried ‘among the Lintons…under the chapel-roof; but in the open air with a head-stone.’ She apathetically tells him: “You may please yourself, whether you go to them, or come to me!”

And what does Edgar do?—which only strengthens her resolve—he asks: “Am I nothing to you, any more? Do you love that wretch, Heath—?” Edgar does not know he’s just labeled his beloved wife, a wretch. Remember: Catherine believes Heathcliff, ‘is more [herself] than [she is].’

After threatening to jump out that open window Catherine makes her feelings clear:

“What you touch at present, you may have. My soul will be on that hilltop before you lay hands on me again. I don’t want you, Edgar; I’m past wanting you.”

Wow! This is one of the most powerful utterances in the entire novel. Catherine is telling Edgar her body (‘what you touch at present’) is to be buried (‘you may have’).

Her soul will be roaming the moors, alongside Heathcliff.

“Return to your books,” she tells him, the man who has just called her a wretch. Making clear she intends to depart his world, she adds, “I’m glad you possess a consolation, for all you had in me is gone.” And so…we return to books.

‘Heathcliff has your permission to come a-courting…’

January 1784-The Same Day

I am not particularly fond of Ellen Dean. In my opinion, she causes more trouble than she helps to dissuade—Mrs. Humphrey Ward, points out in her 1900 “Introduction” to Wuthering Heights:

“Absurd and contradictory…Nelly Dean does the most treacherous, cruel, and indefensible things, simply that the story may move.”

Edgar Linton—it turns out—is positively livid when he finds his beloved Catherine in such frail condition. He blames Nelly for keeping his wife’s condition from him. Were you surprised by Nelly’s saucy reaction to her master’s disappointment?

“The next time you bring a tale to me, you shall quit my service, Ellen Dean,” [Edgar] replied.

“You’d rather hear nothing about it, I suppose, then, Mr. Linton?” said [Nelly] “Heathcliff has your permission to come a-courting to Miss {Isabella] and to drop in at every opportunity your absence offers, on purpose to poison [Catherine] against you?”

“Ah! Nelly has played traitor,” [Catherine] exclaimed, passionately. “Nelly is my hidden enemy. You witch! So you do seek elf-bolts to hurt us! Let me go, and I’ll make her rue! I’ll make her howl a recantation!”

Catherine is livid, too—conjuring rustic superstition and threatening her foster-sister!

As we continue reading, take notice to what Mrs. Ward (in 1900) referred; in many instances Nelly enables Heathcliff and, in others, ‘Nelly [plays] traitor!’ She is often absurd and continually, contradictory!

When Nelly leaves the Grange to fetch the doctor, we gain insight into what has been happening while Catherine has been deliriously plucking feathers from her pillow…

At two o’clock in the morning, under the dark of a new moon, a floating white spectre is our first mysterious hint. It is Fanny, Isabella’s little white springer spaniel, gasping and hanging by a handkerchief. The dog, Nelly explains, was suspended outside on a bridle hook driven into the garden wall.

Superstition has been delicately woven by Brontë through this entire chapter. In this episode it continues: “I saw something white moved irregularly, evidently by another agent than the wind,” Nelly tells Lockwood. “Notwithstanding my hurry, I stayed to examine it, lest ever after I should have the conviction impressed on my imagination that it was a creature of the other world.”

Do you recall Fanny from the scene in Chapter VI, seven years earlier?

Fourteen-year-old Edgar and eleven-year-old Isabella are witnessed by Heathcliff and Catherine after nearly pulling her in two: ‘[the] little dog shaking its paw and yelping.’

This morning, when Nelly Dean releases the animal and lifts it into the garden, Fanny escapes certain death. Nelly continues on her way to find Kenneth—who happens to be exiting his house, on his way to another patient.

Isn’t Brontë’s layering of gossip just brilliant in this episode?

First, Nelly and Kenneth exchange a bit of information: Kenneth tells the housekeeper that he has it on good authority: Isabella intends to run off with Heathcliff! His source claims Heathcliff attempted to coerce Isabella into leaving just the evening before but she hesitated, promising she will accompany him the next time they meet.

Hours later, much to Nelly’s chagrin, the household wakes to learn a boy who fetches the milk told Mary, a young servant at the Grange, that the daughter of the blacksmith (located two miles out of Gimmerton) told him that Heathcliff visited her father’s shop not very long after midnight to ‘have a horse’s shoe fastened.’

And, who was accompanying him? Miss Isabella Linton!

‘…from the pen of a bride just out of honeymoon…’

March 1784

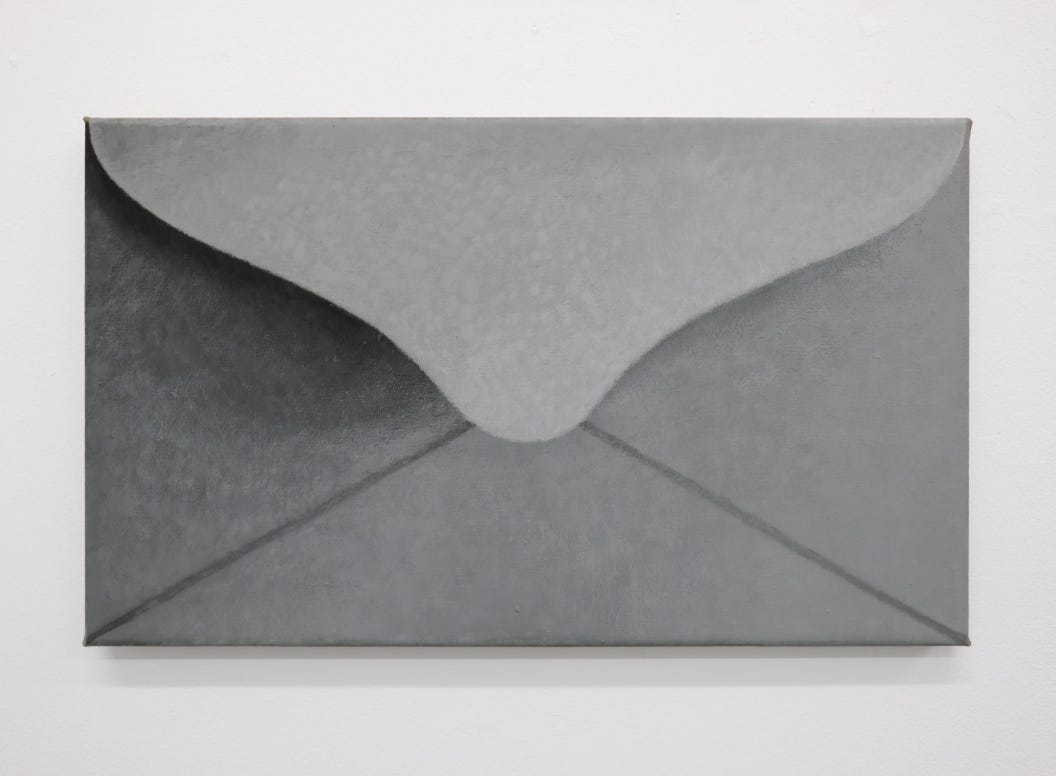

Letters play an important narrative role in Wuthering Heights—we’ll see this especially in Volume Two of the novel. A lengthy letter from Isabella to Nelly provides us with a glimpse into her life after Thrushcross Grange.

When Chapter XIII begins, two months have passed (in 1784) and Catherine Linton has endured, ‘what was denominated a brain fever.’ Nursed by a loyal and dedicated husband, she survives. ‘[Edgar] knew no limits in gratitude and joy when Catherine’s life was declared out of danger.’

Heathcliff, accompanied by Isabella, remained a ‘fugitive’ those two months. In the first six weeks after their departure, eighteen-year-old Isabella Linton forwarded a brief missive to her brother, in which she revealed: she married Heathcliff.

It appeared dry and cold; but at the bottom was dotted in pencil an obscure apology, and an entreaty for kind remembrance and reconciliation, if her proceeding had offended him; asserting that she could not help it then, and being done, she had no power to repeal it.

Edgar did not reply to the letter. He was far too overjoyed by his own wife’s recovery and besides, he is going to be a father—Nelly tells Lockwood: ‘his lands secured from a stranger’s gripe, by the birth of an heir.’

Catherine Linton is pregnant. Were you surprised to read this? It certainly is tucked in neatly between pillowcases draped with golden crocuses and Isabella’s letter, isn’t it? Let’s pause a moment to reflect…

Spring/early summer 1783: Edgar Linton and Catherine Earnshaw are married.

September (Harvest Moon) 1783: Heathcliff returns.

Isabella falls in love with Heathcliff’s, ‘physical and moral beauty’ and;

January 1784: Heathcliff and Isabella Linton are married.

It is now March 1784—and Catherine (Earnshaw) Linton is pregnant.

Nelly Dean saw Isabella Linton going to bed on the evening she left the Grange. We know this, because Nelly tells Lockwood she remembers seeing Fanny, the springer spaniel, follow his mistress up the stairs.

According to the blacksmith’s daughter, Isabella was with Heathcliff two miles out of Gimmerton just after midnight. We now know, they eloped.

When we come to this letter—Isabella’s 1784 letter to Ellen Dean—we are made aware that Isabella is deceased (by 1801): ‘I’ll read it, for I keep it yet. Any relic of the dead is precious, if they were valued living.’

Isabella begins her letter to Nelly by asking: ‘Is Mr. Heathcliff a man? If so, is he mad? And if not, is he a devil?’ This is when the character of Heathcliff (in my opinion) becomes especially difficult to define.

Who is Heathcliff up until now? We know:

the favored child (and victim of bullying), Heathcliff;

the sullen adolescent (and victim of bullying), Heathcliff;

the confident young adult and self-made man, Heathcliff;

Who is this individual who prompts Isabella to ask, “What have I married?”

Heathcliff has regressed to the ‘it’ of Chapter IV. We can only imagine (at least in this chapter) what transpired when he and Isabella eloped. We know that when Heathcliff left Thrushcross Grange he’d been scolded by Catherine:

“Quarrel with Edgar, if you please Heathcliff,” said Catherine arguing with him in the Linton’s kitchen months ago, “and deceive his sister; you’ll hit on exactly the most efficient method of revenging yourself on me.”

And forbidden by Edgar, he is barred from ever returning to Thrushcross Grange.

When Heathcliff marries Edgar’s sister he 1.) is in possession of property which once belonged to Edgar and 2.) he now (potentially) gains access to additional possessions belonging to Edgar. The little boy who had nothing was taught by the Earnshaws and the Lintons that one’s social status and significance is determined by his appearance and tangible possessions. Isabella Linton is now Isabella Heathcliff. And like Hindley degraded Heathcliff, Heathcliff will degrade Isabella.

Let’s talk about Isabella…(I’m lookin’ at you, )

Isabella is a character I often overlook and a comment left on last week’s summary post encouraged me to re-examine her in this reading. Bea says:

I have always liked Isabella - I would love to see a well written account from her point of view. I think she has hidden strength.

Absolutely. I agree! So much of what we know about Isabella comes (obviously) from Nelly’s narrative, but also, from the letter mailed to Nelly just weeks after she elopes with Heathcliff. Scholars have debated the meaning of Isabella’s characterization of Heathcliff for decades—‘Is he mad? Is he a devil?’

Her inquiry may be interpreted in a number of ways—but I think we can all agree, he behaves in a manner with which Isabella is entirely unfamiliar.

What do we already know about Isabella?

Isabella’s father was landed gentry and a Justice of the Peace, as is her brother, Edgar.

She was raised attending church and was educated by Shielders, the curate.

When Isabella first became acquainted with Heathcliff she was a child of eleven; Catherine—having been bitten by Skulker, the Linton’s bulldog—was carried into the family’s drawing room (with Heathcliff accompanying her).

Heathcliff’s appearance (and his cursing) resulted in him being called, “A wicked boy!” by Mrs. Linton and Mr. Linton blamed Hindley for raising both children in heathenism.

We can reasonably assume Isabella shares the worldview and beliefs of her parents. She will be uncomfortable with heathenism (e.g. a lack of Christian piety), profanity will offend her, and we know from her letter—as a lady, she expects to be treated with some level of respect. So, at the very least Heathcliff could have treated her crudely, barbarously and showed here little respect—at the worst, he may have physically or sexually assaulted her. It’s interesting though that neither Joseph nor Hindley make any remark(s) to demonstrate evidence of physical abuse; and she intends to share a bedroom with her new husband—only to be dissuaded.

Heathcliff informs Isabella his bedroom is his alone.5 And she tells Nelly, “He told me of Catherine’s illness, and accused my brother of causing it; promising that I should be Edgar’s proxy in suffering, till he could get a hold of him.”

What is Heathcliff’s definition of Edgar’s suffering, we wonder?

When Hindley suggests Isabella, “Be so good as to turn [her] lock and draw [her] bolt,” when she goes to bed, he too assumes she will be sleeping with Heathcliff.

I’m curious…what did you think of the conversation between Hindley Earnshaw and the new Mrs. Heathcliff? It’s clear Hindley has lost Wuthering Heights to his foster brother; he makes mention to Isabella: “I will have it back!” And we, as readers, are wondering, What has happened? We may also be wondering…did Hindley just confess to Isabella that he intends one day to murder Heathcliff?

This is the scene in which I believe Isabella’s hidden strength begins to quietly enter the picture: Isabella is entranced by Hindley’s ‘curiously constructed pistol.’

“How powerful I should be possessing such an instrument!” she admits to thinking, “I took it from his hand, and touched the blade…[Hindley] looked astonished at the expression on my face…it was not horror, it was covetousness.”

This is likely the first time Isabella Linton recognizes she has options. Likely, for just a moment, she imagines killing Heathcliff herself; maybe she realizes if Hindley kills him, she will be free. And I believe this is the day, Isabella Linton begins to dream of a life without Heathcliff. We’ll see what happens…

‘…in such a wilderness as this…’

March 1784

We have come to the final chapter of this week’s reading assignment and the final chapter in what is Volume One of Wuthering Heights.

In this chapter we gain insight into Heathcliff’s version opinion of his union with Isabella. Edgar has allowed Nelly to visit the Heights and there, she witnesses the decline of both the house and Isabella. And again, we’re looking through windows.

I saw her looking through the lattice, as I came up the garden causeway, and I nodded to her; but she drew back as if afraid of being observed.

I entered without knocking. There never was such a dreary, dismal scene as the formerly cheerful house presented! I must confess that, if I had been in the young lady’s place, I would, at least have swept the hearth and wiped the tables with a duster. But she already partook of the pervading spirit of neglect which encompassed her.

Her pretty face was wan and listless; her hair uncurled, some locks hanging lankly down, and some carelessly twisted round her head. Probably she had not touched her dress since yester evening.

Heathcliff was ‘the only thing there that seemed decent,’ muses Nelly. She recalls, in fact, ‘he never looked better.’ In describing the interior to Lockwood, Nelly believes a home is cheerful if the hearth is swept and the tables wiped. During her tenure at the Heights she kept the house looking cheerful, but she and Hindley were both bullies and, Catherine, ‘was never so happy as when [they] were all scolding her at once.’

Heathcliff likely looks well because finally he is no longer berated, pinched, struck, or beaten.

In this chapter, Isabella and Heathcliff present Nelly with dissimilar versions of their circumstance (and Heathcliff remarks on the genesis of their union). First, Heathcliff questions Nelly concerning Catherine. The housekeeper explains, “she’ll never be like she was, but her life is spared.” She arouses Heathcliff’s concern and provokes him by adding, Edgar, “is compelled of necessity, to be [Catherine’s] companion, [and he’ll] only sustain his affection hereafter by the remembrance of what she once was, by common humanity, and a sense of duty.”

Is Nelly suggesting Edgar remains by Catherine’s side only out of human (perhaps, Christian?) kindness and a sense of duty (as her lawful husband)? Do you think she intends to provoke Heathcliff—whether or not she intends to, she does.

Heathcliff is incensed. “Do you imagine that I shall leave Catherine to his duty and humanity?” he asks, “And can you compare my feelings respecting Catherine, to his?”

This next passage is worth a close reading. After Heathcliff demands, “I will see her!” he explains the difference between his love for Catherine and Edgar’s ‘shallow cares.’

“I say, Mr. Heathcliff,” [Nelly] replied, “you must not—you never shall, through my means. Another encounter between you and the master would kill her altogether!”

“With your aid that may be avoided,” he continued, “and should there be danger of such an event—should he be the cause of adding a single trouble more to her existence—why, I think, I shall be justified in going to extremes!”

Remember, Heathcliff blames Edgar for Catherine’s current condition.

“I wish you had sincerity enough to tell me whether Catherine would suffer greatly from his loss. The fear that she would restrains me: and there you see the distinction between our feelings.”

Heathcliff has no desire to cause Catherine any distress. He is totally submissive to her at all times. If Cathy would suffer, he will not cause Edgar physical harm.

Did you notice? Heathcliff makes a clear distinction between himself and Edgar:

“Had he been in my place, and I in his, though I hated him with a hatred that turned my life to gall, I never would have raised a hand against him…I never would have banished him from her society, as long as she desired his.”

Do you believe Heathcliff—that he would have tolerated a friendship between Cathy and Edgar? What do you think of his description of what he would do if Catherine’s regard for Edgar should ever dissolve—again…a bit vampiric, don’t you agree?

“The moment her regard ceased, I would have torn out his heart, and drank his blood!”

Emily Brontë has convinced me of Heathcliff’s devotion to Catherine. Chapter-after-chapter she has demonstrated his stoicism and his patience. And she has shown me Heathcliff will inflict pain on anyone or anything only if if should please Cathy.

He tells Nelly: “If you don’t believe me, you don’t know me.”

Heathcliff—I do believe—would have tolerated Catherine’s friendship with Edgar Linton: “I would have died by inches before I touched a single hair of his head!” Do you remember Catherine’s very own speech to Isabella, from last week’s reading?

I never say to him, ‘Let this or that enemy alone, because it would be ungenerous or cruel to harm them;’ I say, ‘Let them alone, because I should hate them to be wronged…

I’ve read this chapter over a dozen times and listened to the audiobook half a dozen. I’m fascinated by Brontë’s authorial decisions. She disguised from readers, the three year absence of Heathcliff—we have no idea what he’s experienced. Keep in mind, he is still only nineteen or twenty-years-old. Eighteen-year-old Isabella was with him for two months—on the run?—we have no idea what she’s experienced.

Brontë uses a he said-she said dialogue to provide hints and we are assigned the task of deciding who is telling the truth. Feminist readings often regard Heathcliff’s dialogue (in this chapter) as hinting at something sexually perverse.6

Let’s examine this episode:

When Isabella musters the nerve to defend Edgar’s love for Catherine (and Catherine’s for Edgar), Heathcliff observes: “Your brother is wondrous fond of you too, isn’t he? He turns you adrift on the world with surprising alacrity.7” This is stated scornfully, and results in Isabella’s defense of her brother. She clarifies that Edgar knows nothing of her suffering—knows nothing of Heathcliff’s cruelty, nor her unhappiness living at the Heights. She has written a single note to Edgar—one, she tells us, was viewed by Heathcliff (remember his own words: ‘We have no secrets between us.’)

Do you get the feeling that Heathcliff is irked by the fact that Isabella has not shared with Edgar, any of her distress? He begins to tear her down in front of Nelly:

“She degenerates into a mere slut!

If you are a contemporary American, you likely believe Heathcliff is attempting to characterize Isabella as promiscuous. He is not; he is describing her as slovenly, or unclean. Unfortunately, to a modern ear, his next few statements also sound sexual:

“She is tired of trying to please me, uncommonly early. You’d hardly credit8 it, but the very morrow of our wedding, she was weeping to go home. However, she’ll suit this house so much better for not being over nice, and I’ll take care she does not disgrace me by rambling about.”

I confess, it took many close readings of this exchange for me to recognize Heathcliff is saying Isabella’s physical appearance and degraded countenance will disgrace him; he is not telling Nelly she is sexually promiscuous.

Moments ago Heathcliff might have been dissuaded from further degradation of his wife, but Nelly suggests he furnish Isabella with a maid and treat her kindly:

“Whatever be your notion of Mr. Edgar, you cannot doubt that she has a capacity for strong attachments, or she wouldn’t have abandoned the elegancies, and comforts, and friends of her former home, to fix contentedly, in such a wilderness as this, with you.”

What Brontë achieves in the lengthy passage which follows—initially directed at the housekeeper, but then addressed to young Isabella—succinctly provides readers with Heathcliff’s current frame of mind as well as his intention in marrying Edgar Linton’s sister—before and after the nuptials.

Heathcliff orchestrated a role-reversal (in my opinion) much like the one exacted upon Hindley. He admitted to Isabella, she is to be a proxy for Edgar. The degradation of a member of Edgar’s family is as effective as degrading Edgar (in the eyes of Heathcliff).

Is it only me, or does Heathcliff appear mildly annoyed she is slow to react to his psychological abuse? His sarcasm (“Are you sure you hate me?”) is said in such a disgusted tone, I believe him when he suggests Isabella is intoxicated by him.

‘A hero of romance,’ he calls himself. I wonder if Brontë laughed softly while writing that self-characterization—did she know generations of readers would struggle with how to accurately label Heathcliff?

I’m curious…do you believe Heathcliff when he declares Isabella cannot accuse him of ‘showing one bit of deceitful softness?’ Again, I do. I believe that sadly, Isabella knew Heathcliff only through his relationship with Catherine. Remember, she spent time in the presence of Cathy and Heathcliff (walking on the moors)? She observed their brand of romance.

When Heathcliff hangs ‘her little dog,’ (likely to quiet its barking), he discovers, ‘no brutality disgust[s] her;’ I wonder if naïvely she believed behaving like an Earnshaw might earn from him the same adoration he feels toward Catherine?

Heathcliff confesses: “I’ve sometimes relented, from pure lack of invention, in my experiments on what she could endure, and still creep shamefully cringing back!” This is closely followed by his clarification that her brother Edgar, who is also the Justice of the Peace may rest easy: “[Heathcliff has] avoided…giving [Isabella] the slightest right to claim a separation…”

Two things to mention…

Not until 1878, did power to grant judicial separations and maintenance (alimony, child support) to the wives of husbands who had been convicted of aggravated assault against them extend to local Justices of the Peace (e.g. Edgar Linton) or magistrates.9

Heathcliff declares Isabella endures all of his abuse, to the degree he has literally run out of ideas of how to mistreat her. This statement is occasionally linked with sexual abuse. Again, I disagree. I believe Heathcliff’s statement: he’s avoided giving Isabella the right to claim a separation. This demonstrates Brontë’s knowledge of the law.

She (in my opinion) is not suggesting Heathcliff has explored all manner of sexual depravity and Isabella simply endures it all—but I do believe he is guilty of verbal (psychological) abuse and/or physical battery.

Between 1700 and 1857, a full divorce which allowed re-marriage was by a Private Act of Parliament. The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 was adopted, but grounds for divorce in the United Kingdom remained substantially the same.

Adultery remained the sole grounds for divorce, although wives could now allege cruelty and desertion, in addition to the husband’s adultery, in order to obtain a divorce.10 11

Following Heathcliff’s version of their union, Isabella ‘irefully’ details her experience. She tells Nelly, “He’s a lying fiend, a monster, and not a human being!” She eludes to Heathcliff telling her she has every right to leave him, and perhaps she’s tried. Isabella confirms (again) that Heathcliff maintains: he has married her only to gain power over Edgar.

The eighteen-year-old declares she hopes that one day, “he may forget his diabolical prudence,” and kill her—she would rather be dead than living in her situation. This, of course, breaks every reader’s heart. Interestingly, what Brontë achieves next, is to characterize Isabella as infantile (“There—that will do for the present…this is the road upstairs, child!”). When she—undisciplined—refuses to leave the room so the adults may talk, Heathcliff seizes and thrusts her from the room.

It’s in this final episode I sense Heathcliff’s exasperation executing his own diabolical plan. He recognizes he hastily married Isabella—whom he despises—and returned to the neighborhood only to learn Edgar couldn’t care less, and Catherine is still dying.

‘I’ll haunt the place…’

March 1784

Do you agree that oft times you feel uncomfortable while reading Wuthering Heights? I sometimes agree with Edgar—I’ve become habituated to Heathcliff’s baseness. I am surprised by how I easily forgive his behavior. I’ll be the first to admit it.

His pure, organic love for Catherine surfaces just before or immediately after his most questionable behavior. Until this visit from Nelly, he has only perpetrated “Edgar and The Hot Applesauce Incident of Christmas 1777” and kicking Edgar’s chair. He hardly has seemed a legitimate threat. Now, we wonder if he has truly committed domestic violence against Isabella Linton? In her absence he regresses to his adolescent love for Catherine and tells Nelly: “I only wish to hear for myself how she is, and why she has been ill; and to ask if anything I could do would be of use to her.”

Are those the words of, ‘a lying fiend, a monster and not a human being?’

Only after he threatens to ‘knock [Edgar] down’ and draw pistols are we reminded of his penchant for violence. Emily Brontë maintains a sense of unquiet, doesn’t she? In Heathcliff’s final plea for securing Nelly’s aid in seeing Catherine he utters his most convincing argument, pleading his case with legitimate sagacity.

I will close my lengthy summary by closely examining each of his sentiments:

“It is a foolish story to assert that Catherine could not bear to see me…

You say she never mentions my name, and that I am never mentioned to her. To whom should she mention me if I am a forbidden topic in the house? She thinks you are all spies for her husband. Oh, I’ve no doubt she’s in hell among you!”

Remember, we have no idea what Catherine said to Heathcliff in those minutes they were alone in the kitchen—before Edgar appeared on Nelly’s urging. Perhaps she has expressed wariness regarding Edgar’s staff’s allegiance?

“I guess by her silence, as much as any thing, what she feels.”

Heathcliff knows Catherine. If Catherine is silent, she is defeated. Remember when Hindley banished them to the back-kitchen and Cathy took to quietly journaling?

“You say she is often restless, and anxious-looking—is that a proof of tranquility? You talk of her mind being unsettled. How the devil could it be otherwise, in her frightful isolation.”

Not unlike being sequestered in a loft listening to Joseph preach or imprisoned in a back-kitchen, Heathcliff recognizes isolation in Thrushcross Grange is detrimental.

“And that insipid, paltry creature attending her from duty and humanity! From pity and charity! He might as well plant an oak in a flowerpot and expect it to thrive, as imagine he can restore her to her regular vigour in the soil of his shallow cares!”

I’m wondering if Nelly regrets characterizing Edgar’s love for Catherine in such a way to Heathcliff? I can’t help but believe she’s not witnessed romantic love between Edgar and Cathy…or why on earth would she have defined his attentions as so, familial?

What’s Next?

Next week’s assignment includes three chapters (Volume II: Chapters I-III/15-17). Catherine receives a visitor. Spring arrives. A baby is born and a life is lost. A murder is attempted and someone runs away. Coincidentally, the episodes in these chapters begin Palm Sunday and end around Good Friday 1784.

NO spoilers.

Contains spoilers!

I could go on and on here…Lockwood is enclosed in the box bed, avoiding the residents of the house (keeping them out). He dreams of an apparition at his window—a liminal space—it is the child-ghost of Catherine Earnshaw; Catherine wishes to be let in, Lockwood uses violence to keep her out, Heathcliff begs her to come in.

I promise one day this theme will be given an entire essay!

Hirtle K. B. Uncanny or Marvelous?: The Fantastic and Somatoform Disorders in Wuthering Heights. Dallhousie University, 2011

And what a room! Did you take notice to Brontë’s description of Heathcliff’s bedroom? Valances wrenched from their rings, bent iron rods, damaged chairs and dented walls. Perhaps this is an indication of Heathcliff’s violent temperament—or, is this Hindley’s former bedroom (damaged in drunken rages), now occupied by Heathcliff?

I disagree.

: promptness in response : cheerful readiness

:believe it

Family Search. “Divorce in England and Wales.” Retrieved April 10, 2025.

UK Parliament. “Obtaining a Divorce.” Retrieved April 10, 2025.

In 18th century England a single act of consummation followed by a sexless marriage made the marriage valid; proving sexual dysfunction could result in annulment (Begiato, J. Sex and the Church: Religion, Enlightenment and the Sexual Revolution, 2017).

I’m nearing the very end (sorry - reading ahead, I can’t stop!) and so I am being careful in not putting spoilers here. But I have come to the conclusion that the only character who is actually truthful is Isabella….

There is more violence and death than romance or nature in this story so far. I wonder what Emily was thinking as she roamed outside the house. Pinching, cutting, threatening, and ostracizing--I would have to reread to count all the occasions.