Welcome to Week Six of our Wuthering Heights read-along…

This week’s assignment is Volume 2: Chapters 4-8 (or, 18-21)

What Happens in Chapters IV-VIII/4-8/18-27?

It is now 1797, twelve years have passed since the death of Catherine Earnshaw Linton and the birth of her daughter, Cathy—‘a real beauty in face, with the Earnshaws’ handsome dark eyes, but the Lintons’ fair skin, and small features, and yellow curling hair.’

Characters in our Week Six reading assignment (including Animals): Ellen “Nelly” Dean • Catherine “Cathy” Linton • Edgar Linton • Minny • Isabella Linton Heathcliff • Linton Heathcliff • Hareton Earnshaw • Charlie • Phoenix • Joseph and, Heathcliff

‘The summer shone in full prime…’

Summer 1797

In the first chapter of this week’s assignment we meet thirteen-year-old Cathy Linton.

She was the most winning thing that ever brought sunshine into a desolate house…Her spirit was high, though not rough, and qualified by a heart sensitive and lively to excess in its affections. That capacity for intense attachments reminded me of her mother; still she did not resemble her, for she could be soft and mild as a dove, and she had a gentle voice, and pensive expression: her anger was never furious; her love never fierce; it was deep and tender.

We learn that unlike the children of the previous generation, who were taught by a curate, Edgar Linton took full responsibility for the education of his daughter. Cathy is eager, bright and curious. And she is doted on by her father—spoiled, but sweet.

“Gimmerton was an unsubstantial name in her ears; the chapel, the only building she had approached or entered, except her own home,” explains Nelly, “Wuthering Heights and Mr. Heathcliff did not exist for her; she was a perfect recluse…”

Just a reminder: At this point in the novel, Edgar is thirty-five-years-old, Heathcliff is thirty-three-years-old and Hareton Earnshaw is a young man of eighteen. Nelly, who is the late Hindley Earnshaw’s age, is now forty.

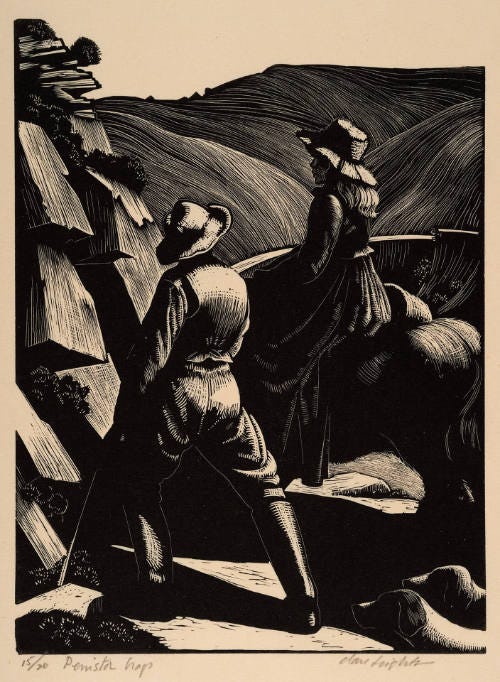

When Miss Cathy observes the hills of Penistone Crags from her nursery window, she is immediately intrigued. So begins, a new story of the Lintons and the Earnshaws.

Ponden Kirk, a crag of gritstone located north of Top Withens and west of Haworth, is believed to be Brontë’s inspiration for Penistone Crags.1

The place was briefly recollected by Catherine Earnshaw, in her delirium:

This bed is the fairy cave under Penistone Crag, and you are gathering elf-bolts! to hurt our heifers; pretending, while I am near, that they are only locks of wool. That’s what you'll come to fifty years hence; I know you are not so now. I’m not wandering: you’re mistaken, or else I should believe you really were that withered hag, and I should think I was under Penistone Crag…2

We must assume Catherine and Heathcliff visited the Crags often in their moorland rambles but Brontë does not provide us with descriptions. Catherine’s daughter now wishes to visit the ‘golden rocks,’ and asks Nelly when she will be old enough. She is curious and wants to know all about them—because she overheard the maids at the Grange talking about the Fairy cave. What thirteen-year-old girl would not wish to visit a Fairy cave? Nelly knows to visit the Crags one must travel past Wuthering Heights and so, she attempts to dissuade Cathy—which of course, only makes her wish more fervently to visit them.

As Nelly tells Lockwood her story, she reminds him that she’d mentioned previously, Isabella lived ‘above a dozen years after quitting her husband.’ Reminding us of the stark difference between the Lintons of Thrushcross Grange and the Earnshaws of Wuthering Heights, Nelly remarks:

“Her family were of a delicate constitution: she and Edgar both lacked the ruddy health that you will generally meet in these parts.”

It is while Edgar Linton is away tending to his sister’s affairs—Cathy Linton decides to explore the Crags (with or without Nelly Dean). Her desire for rambling reminds us of her mother’s passion for the land; when Nelly describes being asked to prepare a basket of provisions so Cathy might pretend she (accompanied by three dogs and her horse, Minny) is crossing the desert as an Arabian merchant, we recollect childhood and the freedom afforded when we had little supervision and all day to imagine.

When Cathy’s old hound returns at teatime—without Cathy—Nelly Dean recognizes her little lady has ventured too far…‘A mile and a half beyond Mr. Heathcliff’s place…’

Cathy had set out earlier, ‘gay as a fairy, sheltered by her wide-brimmed hat and gauze veil.’ Nelly’s worst fear is that she reached the Crags and has fallen, ‘been killed, or broken some of her bones.’ Of course, we learn she has not.

She has discovered Wuthering Heights. Nelly finds her ‘stray lamb seated on the hearth, rocking herself in a little chair that had been her mother’s, when a child.’

Don’t you just adore this scene? Bubbly Cathy, seated in her mother’s chair, laughing and chattering like Catherine would have been; and eighteen-year-old, hard-working farmhand Hareton, staring at her, ‘with considerable curiosity and astonishment.’ Is the scene not reminiscent of Nelly’s earlier words recollecting adolescent Heathcliff, ‘recoiling with angry suspicion’ from Catherine’s ‘girlish caresses.’3

Heathcliff’s servant explains to Nelly that they made Cathy pause at the Heights and that Hareton kindly offered to guide her if she wished to visit the Crags. At this point in the story, are you surprised? Kindness evolved at the Heights since Hindley’s death. Certainly, it seems as if Hareton Earnshaw—a capable adult—remains content living under Heathcliff’s roof.

As is often the case with Emily Brontë’s authorial design, we are not content for long. Hareton’s use of the phrases ‘our house’ and ‘our folk,’ have misled Cathy and when Nelly vaguely references the owner of the Heights, Cathy learns Hareton is not the son of land-owning gentry. Her assumption, that he is ‘a servant’ infuriates him. Now, we are reminded he has been raised in the presence of Hindley, Joseph and Heathcliff.

Hareton grows, ‘black as a thunder-cloud’…and when Miss Cathy commands him to, “Get [her] horse,” as if he is a mere stable-boy, he is incensed.

“And you may come with me,” she permits (showing the reader she does enjoy his company). “I want to see where the goblin-hunter rises in the marsh, and to hear about the fairishes, as you call them—but make haste! What’s the matter? Get my horse, I say.”

My folklore-loving, superstition-believing heart sings when Brontë includes these local tidbits—the Fairy cave, fairishes;4 and, a goblin-hunter rising from a marsh!5

It’s interesting, isn’t it? Cathy (raised by Edgar Linton) reacts to Hareton in the same naïvely demeaning manner that he and his sister, Isabella did upon their introduction to Heathcliff. Isabella Linton compared Heathcliff to a gipsy thief and instructed her father to put him in the cellar. Cathy’s mother, Catherine Earnshaw adored Heathcliff and allowed him to share her bed. Cathy Linton is cautiously tolerant of Hareton—she welcomes his company, but also wants him to know his place.

Unlike Heathcliff, who was always submissive to Catherine, Hareton, (though ‘he could not stand a steady gaze from her eyes’) snaps back at yellow-haired Cathy:

“I’ll see thee damned, before I be thy servant!” growled the lad. "You'll see me what?" asked Catherine in surprise. "Damned--thou saucy witch!" he replied.

When Cathy demands her horse and dogs be brought to her, Heathcliff’s housekeeper makes it clear that she was not hired to serve Miss Linton. And Hareton, she reveals, while he is not the master’s son, is Cathy’s cousin.

Cathy is appalled, and in her disgust she divulges the pending arrival of Linton—the event of which, Edgar certainly did not wish Heathcliff to be aware; in the meantime, remorseful, kind-hearted Hareton is retrieving Minny, Cathy’s horse. He returns with a conciliatory gift: a crooked-legged terrier puppy.

Let’s pause a moment and reflect on Nelly’s description of eighteen-year-old Hareton:

[He] was a well-made, athletic youth, good-looking in features, and stout and healthy, but attired in garments befitting his daily occupations of working on the farm, and lounging among the moors after rabbits and game.

Nelly believes he has a fitter mind than his father, Hindley. She believes he might be a better man if he was not being raised ‘amid a wilderness of weeds,’ but admits (in her narration to Lockwood):

Mr. Heathcliff, I believe, had not treated him physically ill; thanks to his fearless nature, which offered no temptation to that course of oppression; it had none of the timid susceptibility that would have given zest to ill-treatment, in Heathcliff’s judgement.

In other words, Heathcliff only enjoys mistreating those who are timid; he gains no pleasure from abusing and degrading those indifferent or defiant to his behavior. So, because Hareton fears nothing (and no one), Heathcliff simply raised him as a brute.

“He was never taught to read or write; never rebuked for any bad habit which did not annoy his keeper; never led a single step towards virtue, or guarded by a single precept against vice.”

Did you notice, Brontë makes clear to readers that Joseph shares in the degradation of Hareton? In the same way Cathy, as the only child of Thrushcross Grange was raised, spoiled by her father. Hareton, is the only child of Wuthering Heights and was raised, spoiled by Joseph (because he—Hareton—is the head of the ancient Earnshaw family).

Under the ownership of Heathcliff, Wuthering Heights is peaceful and calm since the death of Hindley Earnshaw. According to Nelly, “[Heathcliff] is too gloomy to seek companionship with any people, good or bad.”

By the time Lockwood becomes acquainted with Heathcliff in 1801, he is gloomy yet.

At the end of the chapter we learn that Cathy and her Arabian merchant caravan of dogs—Charlie and Phoenix— were set upon by Hareton with Heathcliff’s dogs.6

Despite the hubbub, Cathy asked Hareton to accompany her onward and, ‘he opened the mysteries of the Fairy cave, and twenty other queer places,’ but neither Nelly nor we—the readers—are provided with details of ‘the interesting objects’ they saw.

Interestingly, if Penistone Crags, is based on Ponden Kirk, folklore maintains that any female who passes through a cleft in its rocks will soon marry.7 Miss Cathy is a girl of thirteen in 1797, and a widow in 1801. Let’s see what happens…

‘A letter, edged with black…’

June 1797

Isabella Linton Heathcliff died in June 1797. Sadly, the lack of information regarding Isabella and her life (and death) after Heathcliff may be why—until a recent comment left by

—I had not thought much about Edgar’s younger sister. Let’s take a moment to put things into perspective…Isabella eloped with and married Heathcliff thirteen years ago. Their son, Linton, is six months younger than his cousin, Cathy. At the time of her death, Isabella is thirty-two-years-old.

We must assume Isabella never divorced Heathcliff, as she would not have had the proof of adultery, nor the means to do so (as it was rather expensive). How did she survive ‘in the south, near London,’ I wonder? Do you wonder the same?

Edgar Linton forwards ‘a letter, edged with black,’ to Ellen Dean, and announces the death of Isabella. He informs her of his return date, bids her ‘get mourning’ (prepare her clothes) for Cathy and arrange a room and other accommodations for his nephew.

What do we already know about Linton Heathcliff?

‘From the first,’ according to Nelly, his mother, ‘reported him to be an ailing, peevish creature.’ It is June when he arrives at Thrushcross Grange and Nelly tells Lockwood, he is ‘asleep in a corner (of the carriage), wrapped in a warm, fur-lined cloak, as if it [is] winter. A pale, delicate, effeminate boy, who might have been taken for [Edgar]’s younger brother, so strong was the resemblance.’

Are you surprised? I’m curious…how did you envision Heathcliff’s adolescent son?

Linton—I’m sure you noticed—is the polar opposite of his father. And, remember the strength his mother exhibited that fateful afternoon she escaped Wuthering Heights? Well, her son certainly has not any of her strength. Cathy cares not; she dotes on him as if she’s been given a new doll—stroking his hair and feeding him as if he is a baby.

Compare this with her mother and Heathcliff at the same age? When Heathcliff was Linton’s age, he already loved Catherine and considered her to be, “so immeasurably superior…to everybody on earth.” And she already loved Heathcliff—by the time she was fifteen she knew, to raise up Heathcliff, she must accept a proposal of marriage from Edgar Linton. Yet, their children, seem (and act) rather…child-like. Is this the result of being raised by Edgar and Isabella, without the stout Earnshaw influence?

As I re-read the passages concerning Linton’s arrival at the Grange I wondered if Linton, too, has been educated at home? His uncle tells Nelly the boy will benefit from ‘the company of a child his own age.’

As you know, just as we are beginning to wonder what Linton’s life has been so far, and imagine what it may be like in the future, Joseph arrives at the Grange. When Heathcliff’s desire to take custody of his son is revealed, Edgar attempts to delay the inevitable, to which Joseph threatens: “Varrah weel! Tuh morn, he come hisseln, un’ thrust him aht, if yah darr!”8

‘Pure heather-scented air…and bright sunshine’

June 1797—Early Morning the Following Day—5 o’clock

Edgar, wishing to avoid a visit from Heathcliff, instructs Nelly to deliver his nephew, Linton, to Wuthering Heights. He instructs her to dissuade shows of concern evinced from Cathy with the simple explanation: “his father sent for him suddenly, and he has been obliged to leave us.”

Another short chapter,9 this one appears to exist so that we may observe comparisons and contrasts between Edgar and Heathcliff, the Grange and the Heights. Linton, the thirteen-year-old city dweller was raised never knowing he ‘had a father.’ We assume Isabella provided no explanation as to Heathcliff’s whereabouts—as Linton shares no tales of, “I thought he died…,” or, “My mamma said…” Instead, Isabella spoke only of Edgar and so Linton is familiar with his uncle and Thrushcross Grange.

Brontë reminds us Heathcliff is always ‘just beyond those hills,’ at Wuthering Heights. “He had business to keep him in the north,” is Nelly’s excuse for why Linton does not know his father; she offers, “your mother’s health required her to reside in the south,” as the reason for their separate living situations.

I must confess, when I read of traveling to the Heights, I do not feel as anxious as perhaps, I should? Emily Brontë’s scenes inside Thrushcross Grange make me feel penned in, and imprisoned. The moment Nelly and Linton exit the park I feel freer and I believe Brontë does this intentionally.

They begin the journey—and Nelly describes, ‘the pure heather-scented air, and the bright sunshine, and the gentle canter of Minny,’…and readers are lulled into a calm, as is Linton.

Heather (Calluna vulgaris), or heath, dominates the moorland. As does Heathcliff. It is evergreen, with small-scaled leaves, which remind me of the leaves found on our U.S. native Arborvitae (Thuja). The pale purple-pink flowers of heather appear from July to September.

“Is Wuthering Heights as pleasant a place as Thrushcross Grange?” Linton asks, ‘turning to take a last (fateful) glance into the valley.’

“It is not so buried in trees and it is not quite so large, but you can see the country beautifully, all round; and the air is healthier for you—fresher and dryer…,” Nelly reassures hesitant southerner Linton.

“And you will have such nice rambles on the moors!” she continues, telling him his cousin Hareton will show him, ‘all the sweet spots.’ She suggests he might, ‘bring a book out in fine weather and make a great hollow [his] study.’

Books—those interior delights which comforted Edgar through Catherine’s sickness—Nelly suggests, may comfort Linton; after he is dropped into a rural farmhouse in the middle of moorland and isolated from anybody literate who might genuinely care for him.

Did you notice, Linton hasn’t the curiosity to ask Nelly: If Wuthering Heights is so fresh, dry and healthy, why’d Mamma have to move south for her…health? Instead, he inquires about his father—Heathcliff.

“And what is my father like?” he asks. “Is he as young and handsome as uncle?”

“He’s as young,” said Nelly, “but he has black hair and eyes, and looks sterner, and he is taller and bigger altogether. He’ll not seem to you so gentle and kind at first, perhaps, because it is not his way…”

“Black hair and eyes!” muses Linton. “I can’t fancy him.”

Light and dark. Good and evil. Linton exclaims he can’t possibly be anything like his father; and Nelly confesses to Lockwood, she noted Linton’s white complexion, his mother’s large, languid eyes, considered his slim frame and she agreed: Linton was nothing like his father.

‘Reared on snails and sour milk’

June 1797—Same Day

Linton’s arrival at Wuthering Heights provides us with a glimpse into daily life there; into the morning ritual of Heathcliff. It is half past six o’clock and the family has just finished breakfast. The housekeeper is wiping off the table, ‘keeping’ the house. The master—Heathcliff—is being updated on a lame horse and Hareton is making ready to head out to the hay-field.

Honestly, I think Brontë is subtly making it clear that Heathcliff is not planning to storm the Grange—or else, he would be there already, right? He cheerfully greets Nelly, telling her he believed he was going to have to “come down and fetch [his] property [himself].”

Heathcliff has called both Hareton and Linton, ‘it’ and refers to them as property; when he installed himself as Hareton Earnshaw’s caregiver he announced: “I have a fancy to try my hand at rearing a young one,” and threatened, if he wasn’t allowed to retain Hareton he would demand his own son be returned to him. Now, Heathcliff is caregiver to both Hindley’s and Isabella’s sons—using only words to secure them.

When Heathcliff became the keeper of six-year-old Hareton, they were already well-acquainted; Heathcliff had saved the child’s life after all. Hareton exhibited fear of his own father, Hindley. But, at only six-years-old, he liked Heathcliff; he ‘played with Heathcliff’s whiskers, and stroked his cheek.’

Heathcliff is thirty-three and his foster nephew is eighteen and now the Heights is peaceful; it is a working farm and farmhouse shared by two men and two servants.

When Linton arrives, Heathcliff exclaims (rather mockingly): “God! What a beauty! what a lovely, charming thing! Haven’t they reared it on snails and sour milk, Nelly? Oh, damn my soul! but that’s worse than I expected—and the devil knows I was not sanguine!” In the final paragraphs10, Emily Brontë introduces us to ‘the turn’ which Heathcliff’s humour has taken since Linton’s arrival.

Heathcliff intends to possess the Grange:

“My son is prospective owner of your place, and I should not wish him to die till I was certain of being his successor. Besides, he’s mine, and I want the triumph of seeing my descendent fairly lord of their estates; my child hiring their children to till their fathers’ lands for wages. That is the sole consideration which can make me endure the whelp—I despise him for himself, and hate him for the memories he revives! But that consideration is sufficient; he’s as safe with me, and shall be tended as carefully as your master tends his own. I have a room upstairs, furnished for him in handsome style; I’ve engaged a tutor, also, to come three times a week, from twenty miles distance, to teach him what he pleases to learn. I’ve ordered Hareton to obey him and in fact, I’ve arranged everything with a view to preserve the superior and the gentleman in him, above his associates.”

‘Nell’ has known Heathcliff his entire life (since coming to the Heights at a young age). When Heathcliff tells her his intentions for Linton, she knows he will remain focused on the goal. Isabella’s son, Linton, the ‘whey-faced, whining wretch’ of a child, whom Joseph calls, ‘yon dainty chap,’ is the long-awaited pawn in this new game.

‘To live all these years such close neighbors…’

Wuthering Heights lies over the hills, four miles from Thrushcross Grange. Linton Heathcliff is raised, Nelly tells us, ‘almost as secluded as Catherine herself.’ On her trips into Gimmerton, she learns the boy is ‘selfish and disagreeable.’

“He must have a fire in summer; and Joseph’s ‘bacca pipe is poison; and he must always have sweets and dainties, and always milk, milk for ever—heeding naught how the rest of us are pinched in winter; and there he’ll sit, wrapped in his furred cloak, in his chair by the fire, and some toast and water, and other slop on the hob to sip at;

Think of Heathcliff. He is frugal, remember? Now, he is wasting precious resources: firewood and milk and wasting money on ‘sweets and dainties,’ plus an education.

“…and if Hareton, for pity, comes to amuse him—Hareton is not bad-natured, though he’s rough—they’re sure to part, one swearing and the other crying.

Hareton has been raised by Heathcliff. He is capable of kindness and empathy, not bad-natured, but his manners and demeanor are, rough.

“I believe the master would relish Earnshaw’s thrashing [Linton] to a mummy11, if he were not his son; and I’m certain he would be fit to turn him out of doors, if he knew half the nursing he gives hisseln.12 But then, [the master] won’t go into danger of temptation; he never enters the parlour, and should Linton show those ways in the house where he is, [Heathcliff] sends him upstairs directly.”

The housekeeper’s gossip in Gimmerton permits us a glimpse into life at the Heights now that Linton has arrived; the adolescent is pampered but Heathcliff cannot stand to witness it.

And, if he had his druthers, he’d allow Hareton to harass the boy (though at this time Hareton clearly lacks his biological father’s penchant for bullying others).

‘Climb to that hillock, pass that bank…’

March 20, 1800—Three Years After Linton’s Arrival

Soon after we begin the longest chapter of this week’s assignment, Cathy Linton turns sixteen. The anniversary of the young lady’s birth is, of course, the anniversary of her mother’s death. And on this particular birthday, Cathy wishes to have a ramble on the edge of the moors. She is familiar with a colony of moor game and wishes to confirm if they’ve begun nesting.

“Climb to that hillock, pass that bank, and by the time you reach the other side, I shall have raised the birds,” Cathy exclaims, gleefully seeking nests hoping to observe eggs.

When Heathcliff and Hareton come upon her, she appears guilty of poaching, as she is on Heathcliff’s land. However, he treats her kind and gentlemanly.

This episode is a bit odd, because Nelly admits to Lockwood she believes the young lady’s Catherine-like gaze is enough to disarm Heathcliff, and he may not wish her any harm. As readers we wonder why Heathcliff would harm any child of his beloved Catherine? We must assume it is because she is part-Linton.

Heathcliff and Hareton are obviously close; Heathcliff treats the young man with a familial kindness. They are often together, mutually involved in the tasks around the farm—think back to the decision-making during the snowstorm in which Lockwood is stranded. Hareton is the child of the man who degraded and abused Heathcliff, but for some reason Nelly immediately believes Heathcliff might desire Cathy’s ‘injury.’

When he invites Cathy to visit the Heights he admits (quite honestly) his intentions. Were you surprised by this? He tells Nelly straight up: He plans to marry off Linton and gain control of Thrushcross Grange. And when Linton and Cathy are reuniting, where is Heathcliff? Lingering by the door. He is always in a liminal space, in this case, ‘dividing his attention between the objects inside and those that lay without.’

I must know…what did you think of Heathcliff’s reaction to his son Linton’s dismissal of Cathy—the boy’s utter apathy? Did you catch the bit about how he covets Hareton?

I was reminded of Heathcliff’s awareness at thirteen that Catherine’s ‘girlish caresses’ were fruitless—at a young age he knew she could never marry him, because of how low Hindley had placed him. Now, Heathcliff recognizes this in Hareton. “But I think he’s safe from her love,” he remarks to Nelly.

Safe from her love. Isn’t that an interesting way of putting it?

It’s in this chapter we also get a glimpse into the sort of courting ritual which might have been shared between Catherine Earnshaw and Heathcliff—it includes rabbits and weasel’s nests.13 I must confess: this sounds like absolute bliss to me. Not every girl desires fine jewelry or wishes to walz.

‘Hareton is damnably fond of me!’

When Linton Heathcliff refuses to escort Cathy outside, Heathcliff instructs Hareton to show her around. And, I’m certain you noticed, the handsome twenty-year-old is happy to oblige despite, as Heathcliff calls it, being tongue-tied.

What did you think of Heathcliff and Nelly’s conversation—recollecting their shared past as foster siblings, and; Heathcliff, confessing his current feelings about his relationship with Hareton?

Mr. Earnshaw saw something in Heathcliff, something worth rescuing. Heathcliff was bullied from the moment he was uncovered from Earnshaw’s cloak. He is bright and well-spoken (being educated by the curate and gleaning what lessons he could, after later being denied an education). Hindley physically assaulted him and degraded him for almost a decade—the only respite being Hindley’s time away at college. Catherine Earnshaw loved him and Heathcliff would do anything for her, he became completely, voluntarily submissive.

Heathcliff has cultivated a different kind of relationship with Hareton—Hareton’s love and submissive behavior hasn’t required violence. Hareton has only ever known Heathcliff as a father-figure and since Catherine’s and Hindley’s deaths, Heathcliff lives and works alongside Hareton as, father and son.

“I’ve a pleasure in him. He has satisfied my expectations. If he were born a fool I should not enjoy it half as much. But he’s no fool; and I can sympathise with all his feelings, having felt them myself…I’ve got him faster than his scoundrel of a father secured me, and lower; for he takes pride in his brutishness. I’ve taught him to scorn everything extra-animal as silly and weak…”1415

Heathcliff recognizes Hareton was born, ‘with first-rate qualities.’ So was, Heathcliff. Hindley kept him low; and desiring to be more, Heathcliff escaped the Heights and raised himself up. Hareton is so low, he desires little; he’s content; and unaware the very land he tills is rightfully his.

“[Hareton] is gold put to the use of paving stones;

Linton was born, ‘an ailing, peevish creature,’ and raised to be a gentleman. He quite literally is, ‘silly and weak.’ He is all emotion—extra-animal feelings and sensitivities.

…and [Linton] is tin polished to ape a service of silver.”16

Hareton has no reason to believe he is anything but gold, even though he is trodden upon like paving stones. Hareton does not know he’s being degraded. He—Heathcliff—knew Hindley reduced him. He sought revenge. But Heathcliff raised Hareton in a way which resulted in love—Hareton will never raise a hand to Heathcliff nor, attempt revenge (because he knows not that he’s been dispossessed).

When Heathcliff sends Hareton out walking with Cathy, he instructs him to: behave like a gentleman, use no bad words, refrain from staring, speak slowly and keep his hands out of his pockets. Heathcliff knows he will abide. It is only after Linton arrives and mocks Hareton’s intellect in front of Cathy does the older, handsome, well-built, esteemed young man of the Heights recognize he is not gold. Heartbreaking, isn’t it?

Hareton lashes out. “If thou weren’t more a lass than a lad, I’d fell thee this minute,” he threatens, and we are reminded of Heathcliff, Catherine and Edgar. I’m certain if there had been a tureen of hot applesauce nearby, Linton would have been scalded.

‘A fine bundle of trash…’

Miss Cathy Linton, having been raised and educated by Edgar, does not find Hareton the least bit charming. He is boorish and (now) bullying in her eyes. Cathy’s attention turns toward her other cousin and becomes the focus of the next nine chapters!

How does their relationship begin? Clandestine letters, carried by the milk-fetcher boy.

Let us remember, Cathy Linton is sixteen-years-old and Linton, six months younger. The love letters the cousins exchange are ‘babyish trash,’ passed between immature, isolated teenagers who’ve spent a total of only four hours together in all their lives.

In the final paragraphs of this final chapter we catch a glimpse of Catherine Earnshaw in her daughter, don’t we? No longer ‘mild as a dove.’17

Remember when we began this reading assignment—‘her anger was never furious?’

“You cruel wretch!” she christens Nelly Dean, after the nurse confronts her about the letters. Were you surprised by this outburst? Behaving like her mother, Cathy retires to her chamber after being forbidden to continue communicating with Linton. She refuses dinner; but unlike her mother, she re-appears at tea, ‘pale and red about the eyes.’ All, because of young Linton Heathcliff, ‘a pale, delicate, effeminate boy.’

Next week’s assignment includes six chapters (V2: Chapters 8-13, or 22-27).18

Illness, sullenness, treachery and kidnapping...the next assignment includes it all!

How are you all doing? A number of you have told me you’re reading ahead, some have fallen behind and a handful admitted you’re waiting until you complete other read-alongs, but…you plan to read Wuthering Heights in the future!

If you’re having difficulty reading the novel, I suggest listening to an audiobook. I listen to a free LibriVox recording read by Ruth Golding—available to stream HERE.

Also, if you prefer to read Substack offline: Might a PDF option aid you?

I hesitate from offering such things because (for example), if you had wished to print last week’s essay it would have required thirty-five sheets of your paper and ink. Or, do you wish to save the essays for internet-free reading on a device?

Let me know your thoughts. Your input shapes and improves future read-alongs!

One more thing…Did you know that in your dashboard there is an option to listen to an audio version of each of my essays? Navigate to the post in your inbox and look in the upper right hand corner for the “Play Audio” arrow. It certainly isn’t perfect, but it’s an accessibility option you may wish to experiment with and see if it helps you. ♡

Support my writing and research: Buy Me a Book | Buy Yourself a Book

Haworth is a village in West Yorkshire, England (located within the south Pennines).

Volume 1: Chapter 12

Volume 1: Chapter 8

fairishes: a West Yorkshire word for fairies. Fairish is its singular form.

Gases caused by organic decay produce light over graveyards, marshes and swamps, this light (chemiluminescence) mimics lantern light; perhaps of a Yorkshire ‘goblin hunter?’

Volume 2: Chapter 4

Folkore abounds in relation to Ponden Kirk; this is one commonly repeated belief.

“Very well! In the morning he will come himself, and throw him out if you dare!“

Volume 2: Chapter 6

Volume 2: Chapter 6

mummy: dust

hisseln: himself

Volume 2: Chapter 7

extra-animal: human feeling, as opposed to animals

Heathcliff has abandoned all human feeling; save for his emotions regarding Catherine. He exhibits only behaviors relegated to the animal kingdom; more appropriately, those actions required for survival. He mates (with Isabella), defends (against Hindley), sires (Linton), etc. And it is all done without emotion, or feeling.

Or, so he thinks. Animals do not hate—but, don’t you think Heathcliff believes he is simply acting out of his desire to retain dominance? He acts in defense of territory. Those are the actions of animals—to retain dominance animals breed, attain and defend territory.

ape: mimic

Volume 2: Chapter 7

Have you seen my new Chapter Conversion Chart?

These summaries are so helpful. I have marked my book where to stop and come look for the wealth your posts provide. This is certainly not a dull book, but the neglect of some of the children does make me sad. The characters feel so real I have to remind myself this is fiction. Or is it fiction? Are aspects of characters personalities and actions taken from the author's brother with a drinking problem? Onward!