Hello! Welcome to Week Two of our Wuthering Heights read-along…

This week’s assignment is Volume I: Chapters IV through VII (4-7)

We meet our second narrator, the housekeeper, Ellen “Nelly” Dean…

We also meet: Mr. Earnshaw, Hindley, Catherine, Mrs. Earnshaw, Frances, Skulker, the housekeeping staff of Thrushcross Grange, Mr. and Mrs. Linton, Edgar, Isabella, and, Shielders.

Also…I have another audiobook suggestion for you this week. This one, available free on LibriVox and narrated by Ruth Golding is very good—she voices all characters and makes a particularly good Nelly Dean. Please let me know what you think if you try it!

So, What Happens in Chapters IV through VII?

Mr. Lockwood mines Nelly Dean for information. We learn Hindley (who was nursed by Nelly’s mother and mentioned in Catherine Earnshaw’s diary) is the elder brother of Catherine. Heathcliff, we discover, is a foundling—rescued (or, snatched) off of the streets of Liverpool by charitable Mr. Earnshaw and brought to Wuthering Heights.

Mr. Earnshaw dotes over Heathcliff. Mrs. Earnshaw disapproves. Young Hindley and Heathcliff become adversaries; but Catherine, she is ‘much too fond of Heathcliff.’

When Mr. and Mrs. Earnshaw are no longer around to keep order in the house, the children become ‘rude as savages’ and a new master and mistress gain the power. A bulldog seizes Catherine, Heathcliff is banished, Edgar and Isabella Linton enter the picture, hormones are racing and in the mind of a scorned, teenage boy, a godless plot of revenge begins to take shape in the Earnshaw’s back-kitchen.

‘What vain weather-cocks we are!’

In the first chapter of this week’s assignment we learn the Grange and its ‘beautiful country’ isn’t necessarily Lockwood’s heaven. Perhaps he is not the misanthropist he believes himself to be; upon his return to the Grange, he immediately seeks company. He decides to pick the brain of the housekeeper, Mrs. Dean, hoping she ‘would prove a regular gossip.’

If you’ve been a reader of Symbolism & Structure for a while, you might have read my essay on the roles of Lockwood and Nelly Dean. The tourist from the south of England, Lockwood is a sort of researcher—similar to a folklorist—gathering information so he might better understand the rustic inhabitants of the Heights. Ellen Dean—like those old wives who gifted us all of our old wives’ tales—is his informant.

His research focus is of course, Heathcliff.

‘A gift from God, though it’s as dark almost as if it came from the devil.’

Thankfully for Lockwood—and us!—Nelly proves ‘a regular gossip.’ Her story begins approximately three decades earlier, in September 1771.

Mr. and Mrs. Earnshaw owned Wuthering Heights. The Earnshaws had two children, Hindley (‘a boy of fourteen’) and Catherine (‘hardly six-years-old’). Nelly tells us that one day—at the beginning of the harvest—Mr. Earnshaw returned from a (sixty miles each way) three-day walk to Liverpool, laughing and groaning, claiming, ‘he would not have such another walk for the three kingdoms.’1

This is the genesis of Nelly’s story—The Story of Heathcliff. The Earnshaw children had been eagerly anticipating souvenirs. Young Hindley had asked his father to bring him a fiddle from Liverpool, and Miss Cathy, who ‘could ride any horse in the stable,’ requested a whip.

Mr. Earnshaw opened his coat and instead revealed: a boy.

We crowded round, and over Miss Cathy’s head, I had a peep at a dirty, ragged, black-haired child; big enough both to walk and talk—indeed, its face looked older than Catherine’s—yet, when it was set on its feet, it only stared round, and repeated over and over again some gibberish that nobody could understand.

Imagine this for a moment. Consider the situation from every character’s point-of-view: Mrs. Earnshaw, adolescent Hindley, immature Catherine and especially, take a moment to consider the seven-year-old, ‘dirty, ragged, black-haired child.’

The next few passages have always struck me as so, so sad. As Nelly tells Lockwood the story of Heathcliff’s arrival, she refers to him as: it. Again-and-again. In fact, she calls the child, it more than ten times while describing his arrival to Lockwood. The final episode in which she calls him it, is especially heartbreaking:

[The children] entirely refused to have it in bed with them, or even in their room, and I had no more sense, so I put it on the landing of the stairs, hoping it might be gone on the morrow. By chance, or else attracted by hearing his voice, it crept to Mr. Earnshaw’s door and there he found it quitting his chamber.

Mr. Earnshaw, learning the child was set on the landing in the hopes he might simply wander off into the moors, punished Nelly for her ‘inhumanity,’ and sent her out of the house. Upon her return to the Heights, the young housekeeper learned the family christened him, Heathcliff, the name of a son who died in childhood.2

Nelly and Hindley both hated Heathcliff—she admits this to Lockwood—and when the older, stronger boy wasn’t physically assaulting the little boy, Nelly was pinching him, astonished that Heathcliff did not shed a tear.

‘I hope he’ll kick out your brains!’

Brontë slips Mrs. Earnshaw’s death into Chapter IV so quietly, you might have missed it. Nelly explains to Lockwood, that after Mrs. Earnshaw’s passing, Hindley began to believe himself usurped by young Heathcliff. The Mr. Heathcliff we met in Chapter I is around thirty-seven-years-old. He is wealthy, stern and intimidating; his demeanor is surly and morose. In this chapter he was an eight-year-old boy. It is in this chapter one of the first episodes of shocking violence occurs. And it is not perpetuated by the child who Earnshaw called, a gift from God, though [he is] as dark almost as if [he] came from the devil:

“Off, dog!” cried Hindley, threatening him with an iron weight, used for weighing potatoes or hay.

“Throw it,” [Heathcliff] replied, standing still, “and then I’ll tell how you boasted that you would turn me out of doors as soon as [Earnshaw] died, and see whether he will not turn you out directly.”

Hindley threw it, hitting him on the breast, and down he fell, but staggered up immediately, breathless and white, and had not I prevented it he would have gone just so to the master, and got full revenge by letting his condition plead for him, intimating who had caused it.

“Take my colt, gipsy, then!” said young Earnshaw. “And I pray that he may break your neck; take him, and be damned, you beggarly interloper! and wheedle my father out of all he has, only afterwards show him what you are, imp of Satan—And take that, I hope he’ll kick out your brains!”

A steelyard balance is used to weigh cotton, straw and produce—like, potatoes—on farms. While this iron weight is an example from the 19th c., let’s reasonably assume the 18th c. weights were similar. This one weighs approximately 221 grams (8 oz).

Now, imagine sixteen-year-old Hindley hurling one at the breast of a child half his age.

Nelly tells Lockwood she convinced young Heathcliff to disguise the source of his injury, even though she knew Hindley had that week given him, ‘three thrashings’ bruising his arm, ‘black to the shoulder.’ Heathcliff, according to Nelly, seldom complained, ‘of such stirs.’3

Her opinion of Heathcliff was never favorable; and so her story (as told to Lockwood) is rife with unflattering details.4 Nelly, is certainly an unreliable narrator.

Let’s see what happens next…

‘No parson in the world pictured heaven so beautifully…’

Chapter V is a short one, but it certainly proves pivotal in the story, doesn’t it? Nelly’s narration teaches us a few things. Sometime in 1774 Mr. Earnshaw sent Hindley away to college (at the urging of the curate). Nelly explains that Mr. Earnshaw’s health had begun to decline5 and she tells Lockwood, Earnshaw was agitated if anyone imposed upon his favorite, Heathcliff.

After Hindley—Heathcliff’s violent oppressor—left for college, Nelly hoped the family might have some peace, but as we learn, Joseph’s antagonizing and zealotry created an atmosphere of unrest.

Catherine, who ‘was much too fond of Heathcliff,’ matured into a ‘wild, wick6, slip’ of a twelve-year-old girl Nelly describes as: ‘never so happy as when we were all scolding her at once, and she defying us with her bold, saucy look.’

Kind-hearted and charitable Mr. Earnshaw died ‘quietly in his chair one October evening;’ and while vinegar-faced Joseph and Nelly Dean called for the doctor and parson, the children, Catherine and Heathcliff, stole away to console one another.

The little souls were comforting each other with better thoughts than I could have hit on; no parson in the world ever pictured heaven so beautifully as they did, in their innocent talk; and while I sobbed and listened, I could not help wishing we were all there safe together.

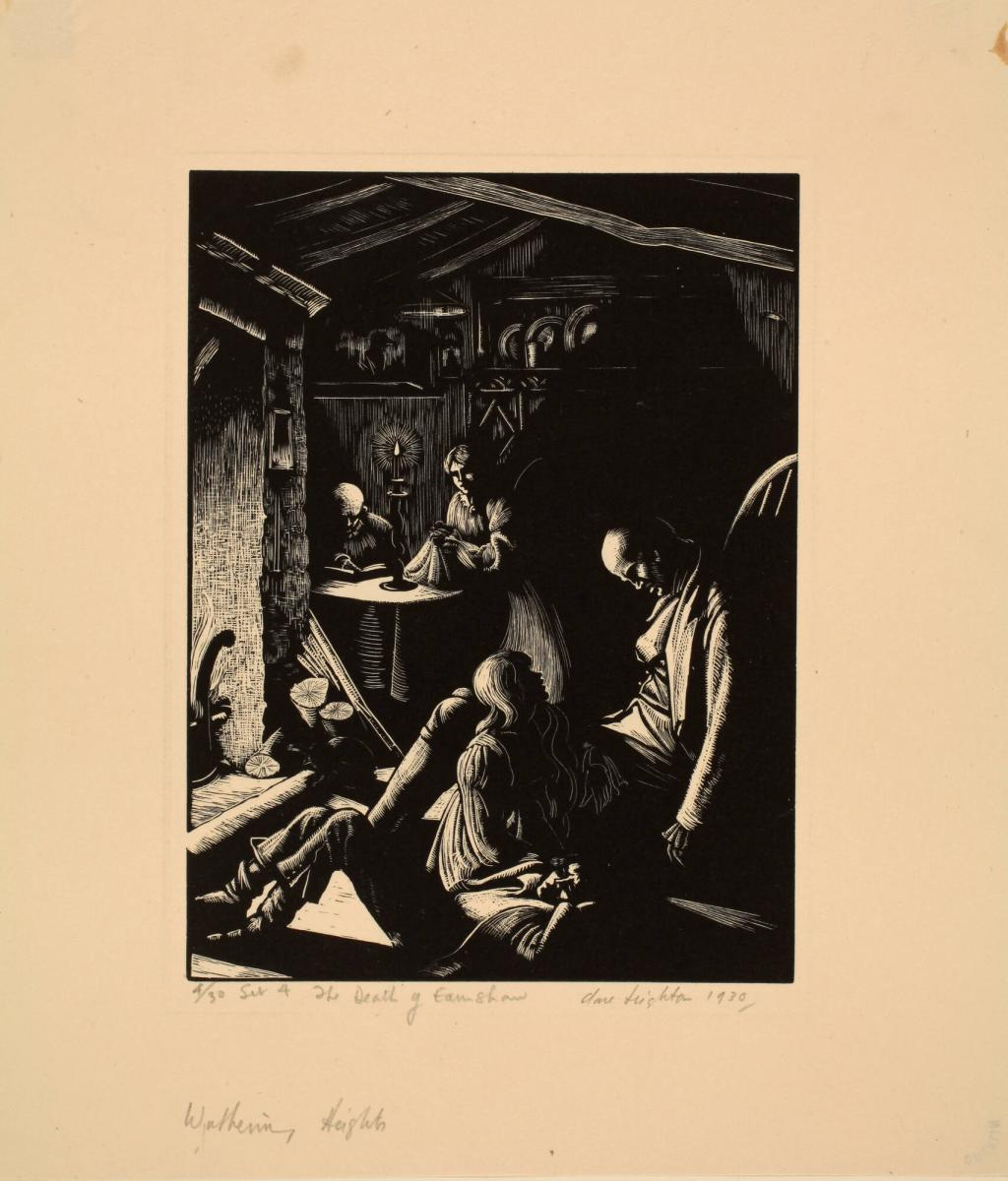

There are a number of subtle details woven throughout this short chapter, don’t you think? Clare Leighton’s woodcut (pictured above) also depicts those details—Joseph and his Bible, Nelly with busy hands and her eyes on the children, and lively Cathy perched by her father’s knee while Heathcliff sprawls submissively on the floor with his head in her lap.

When Earnshaw dies, Nelly, who has lived her life at the Heights, with Earnshaw as the master, is as devastated as the children. Mrs. Earnshaw has passed, Hindley has been sent away and now Mr. Earnshaw is dead. Nelly imagines her own heaven; in which they will all be together. A perfect Victorian vision.

‘She is so immeasurably superior to them.’

October 1777—Chapter VI—Hindley Earnshaw returns to Wuthering Heights. He brings with him a wife and from the onset, Brontë wants readers to recognize she shows symptoms of being consumptive.7

When the chapter begins we learn Hindley is now the master of Wuthering Heights. To put this in perspective, Joseph by this time, has been in service at the Heights for half a century or so,8 and Nelly has lived there, approximately twenty years (she and Hindley are the same age). Hindley and his young wife are master and mistress of the house and the new master is soon reminded of his dislike for Heathcliff.

Hindley’s mistreatment of both Catherine and Heathcliff is what leads to the incident Lockwood read about in Chapter III—the incident which provokes Hindley to banish Heathcliff from the dinner table. He also forbade him from playing with Catherine.

Nelly explains: “It was one of their chief amusements to run away to the moors in the morning and remain there all day, and the after-punishment grew a mere thing to laugh at. The curate might set as many chapters as he pleased for Catherine to get by heart,9 and Joseph might thrash Heathcliff till his arm ached; they forgot everything the minute they were together again…”

The evening Catherine wrote, “How little did I dream Hindley would ever make me cry so! My head aches, til I cannot keep it on the pillow and still I can’t give over,” is the incident described in Chapter VI.

This episode is when all the details from Catherine’s diary are filled in by Brontë.

The Sunday evening they were banished to the wash-house—after attempting to play behind their pinafores under the dresser—Catherine and Heathcliff hatched a plan to escape the Heights and ‘have a ramble at liberty.’ Attracted by interior lights at the Grange, the two decided to spy on their neighbors, the Linton children—Isabella and Edgar.

As you know, their escapade ended in tragedy.

Did you notice the sweet language Brontë assigns to Heathcliff during his narration of the episode? Heathcliff—literature’s perpetual villain, at age thirteen—appreciated the beauty of the Lintons’ ‘splendid’ drawing-room. The Lintons’ appalling behavior was both amusing and confounding. Heathcliff inquired of Nelly, “When would you catch me wishing to have what Catherine wanted,” perplexed by the covetousness of Edgar and Isabella; “or find us by ourselves, seeking entertainment in yelling, and sobbing, and rolling on the ground, divided by the whole room?” Divided by the whole room!

Heathcliff cannot comprehend desiring to be separated from Catherine.

Brontë is beginning to hint at Heathcliff’s veneration of Catherine. When he relates the story of the bulldog seizing her, followed by apologetic pampering by the Lintons, we begin to understand how Catherine is valued by Heathcliff; though he has been tossed out of the Grange as, ‘a little Lascar, or an American or Spanish castaway,’ still he wants only what is best for her:

The curtains were still looped up at one corner; and I resumed my station as spy, because if Catherine had wished to return, I intended shattering their great panes to a million fragments unless they let her out.

He tells Nelly she was given a drink of negus10 and a plateful of cakes. Brontë reveals Heathcliff’s true feelings for his twelve-year-old playmate:

Afterwards, they dried and combed her beautiful hair and gave her a pair of enormous slippers, and wheeled her to the fire, and I left her, as merry as she could be, dividing her food between the little dog and Skulker whose nose she pinched as he ate; and kindling a spark of spirit in the vacant blue eyes of the Lintons—a dim reflection from her own enchanting face—I saw they were full of admiration, she is so immeasurably superior to them—to everybody on earth, is she not, Nelly?

Let’s rewind just a bit and consider how others characterize Heathcliff…

‘Miss Earnshaw scouring the country with a gipsy!’

Do you remember—in Chapter IV—Mrs. Earnshaw asked how her husband could think to bring ‘that gipsy brat’ home from Liverpool, ‘when they had their own bairns to feed and fend for?’

Mrs. Earnshaw characterized Heathcliff—the dirty, ragged, black-haired boy—as a gipsy. And now, Isabella Linton claims, “He’s exactly like the son of the fortune-teller that stole my tame pheasant.”

Her mother exclaims, in disbelief: Miss Earnshaw scouring the country with a gipsy! She cries out despite Edgar Linton explaining he recognizes the children from church.

Mr. Linton ignores his son’s clear recognition of the two and labels young Heathcliff as anything from ‘a little Lascar, to an American, to a Spanish castaway.’

This has been the subject of critical analysis for a century. What is Heathcliff?

I believe Heathcliff, “the dirty, ragged, black-haired child,” is Irish.

He is a lone, seven-year-old boy, discovered by Earnshaw on the streets of Liverpool. He is starving and impoverished. Earnshaw’s initial description of him being, “as dark as if [he] came from the devil,” in my opinion, refers simply to his filthy appearance or possibly, to his ill-temper (after all, he was just snatched off the street). The “gibberish that nobody could understand,” in my opinion, refers to his Irish dialect.11

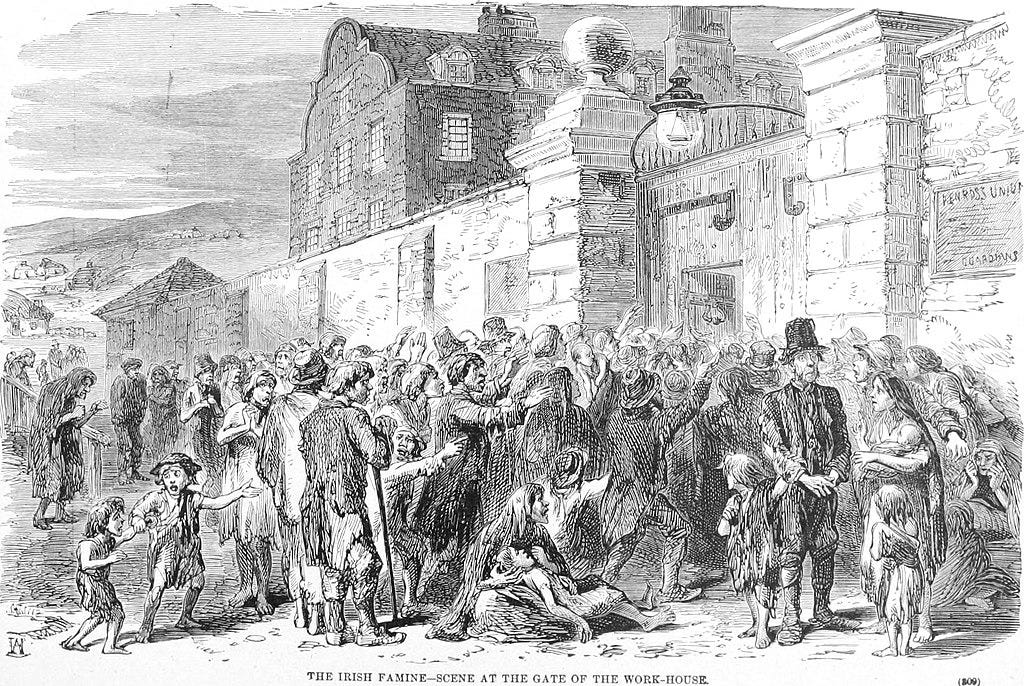

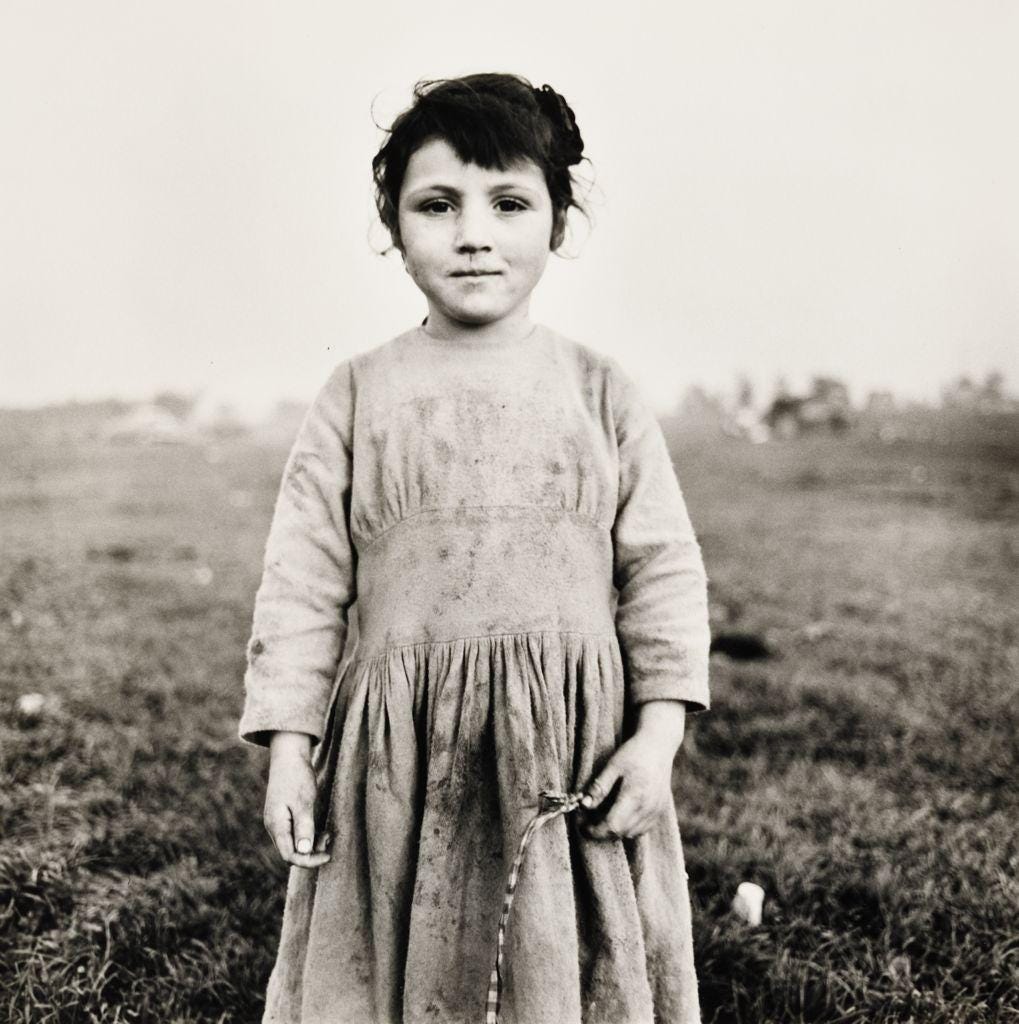

I agree with scholars who assume Emily Brontë based Heathcliff on the children her brother Branwell described seeing in Liverpool; in other words, children displaced by the Irish famine. She was writing during the famine and images of the child victims were printed in newspapers and magazines of the time.

So you may make your own decision about Heathcliff, I’ll provide brief snapshots of the varying ethnicities (and nationalities) with which characters identify him.

Irish Travellers (Mincéirs)

Mincéirs (Irish Travellers) are a traditionally nomadic ethnic minority indigenous to Ireland, distinct from the majority Irish population. Throughout history, varied terminology was used to describe us such as ‘Tinker/Tynkr’, ‘Itinerant’, and ‘Gypsy’.

Dr. Sindy Joyce, Lecturer at University of Limerick

Knowledge of the Irish Traveller community dates to the 1830s. Would the inhabitants of the Heights and the Grange have known of them? Maybe. Would they have referred to them as gipsies? Maybe.

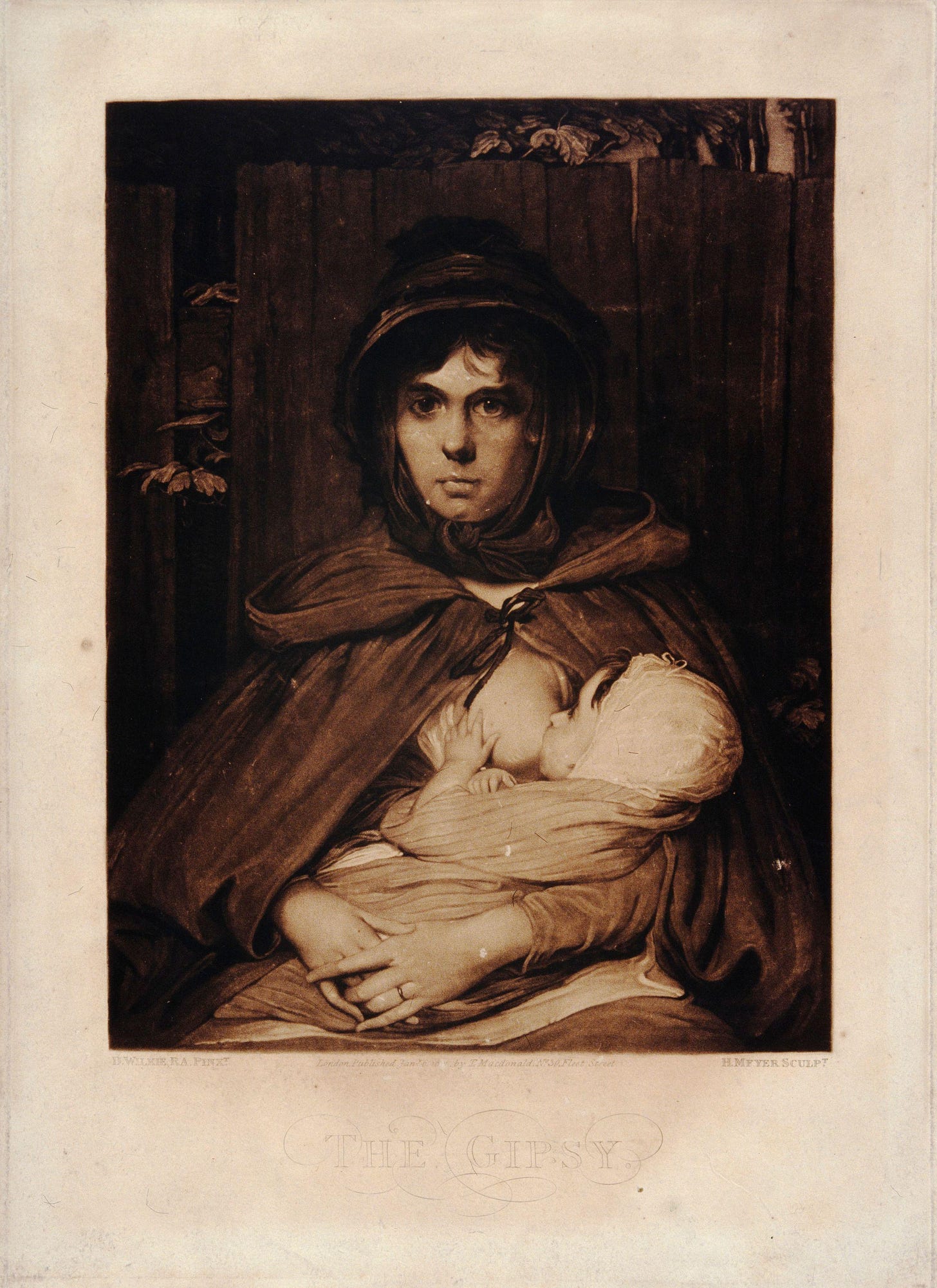

Or, could Heathcliff have been characterized as Indo-Aryan? Consider young Isabella Linton’s reaction to him. The dark-skinned gypsy fortune-teller in the advertisement card pictured above portrays an individual likely considered Romani, an Indo-Aryan ethnic group still often referred to by English speakers as gypsies. The Romani people arrived in Europe around the 14th century.12 Could Heathcliff be Romani? Maybe.

Lascar (East Indian Sailors)

Mr. Linton, when recognizing Heathcliff as the child brought home from Liverpool by Mr. Earnshaw, runs through a number of possibilities for the boy’s origin—one being, a little Lascar. A lascar was a sailor from the Indian sub-continent.

After their service-at-sea, most lascars returned to their homeland but some settled in England, married and started families. Could Heathcliff be a child of a lascar man and a British woman? Maybe.

American or Spanish Castaway

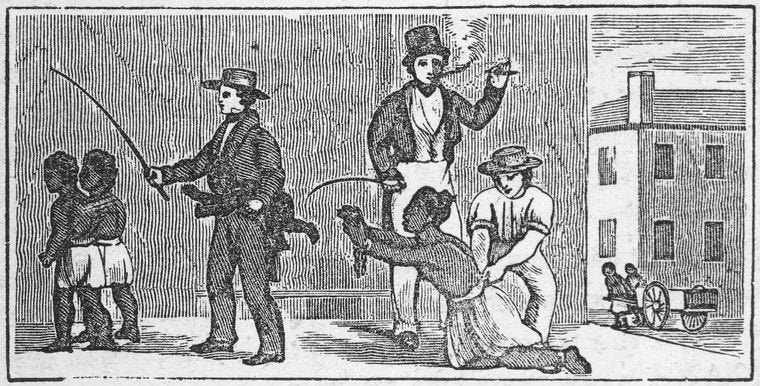

Could Heathcliff be the child of a slave? This is yet another theory critics have explored due to Brontë’s many references to him being ‘dark,’ or ‘black.’13

From about 1500 to about 1865, millions of Africans were enslaved and transported across the Atlantic by Europeans & Americans as a labour force to work, especially on plantations.

Liverpool ships carried about 1.5 million enslaved Africans on approximately 5000 voyages, the vast majority going to the Caribbean. Around 300 voyages were made to North America - to the Carolinas, Virginia and Maryland.

The ships returned to Europe with goods such as sugar, cotton, coffee and tobacco. Liverpool grew rich on the back of trading in enslaved people.14

Additionally, literary critic and editor of The Annotated Wuthering Heights, Janet Gezari notes: castaway in a secular sense refers to being abandoned; in its religious sense, the word refers to someone damned (104).15

‘A good heart will help you to a bonny face, my lad’

As I sit down to write this summary this afternoon, I have the audiobook version of Chapter VII fresh in my mind. It is springtime here in the northern hemisphere; it’s Christmas at the Heights! And, what a Christmas…don’t you agree?

Catherine arrives home from her five week stay at the Grange and she is now a lady. Just like that, everything has changed. Appearing with ‘brown ringlets,’ wearing a hat of ‘feathered beaver,’16 and a fine riding habit, she has been elevated to the same class as the Linton children—while Heathcliff has sunk lower.

Hindley and his young wife, Frances, could not be more pleased. Nelly (judging by her sarcastic, ‘playing ladies maid to the newcomer’ remark) is as surprised as Heathcliff by Catherine’s transformation.

What did you think of Catherine’s initial reunion with Heathcliff?

Brontë describes Christmas Eve at the Earnshaws and we are reminded that Mr. Earnshaw had been a kind, generous, charitable man. Nelly tells Lockwood:

I remembered how old Earnshaw used to come in when all was tidied, and call me a cant17 lass, and slip a shilling into my hand, as a Christmas box.

Feeling a bit of charity herself, Nelly seeks Heathcliff in the barn and encourages him to come inside for some cake; he refuses. She tells Lockwood: the following morning he rose early, ‘and as it was a holiday…[he] carried his ill-humour onto the moors, not re-appearing until the family were departed for church.’

As a thirteen-year-old boy, filthy from farm-work, Heathcliff is quite a contrast to Edgar Linton. Heathcliff recognizes this and before the Linton children arrive for Christmas at the Heights, he asks Nelly to ‘make [him] decent.’

It is during this episode Heathcliff’s ethnicity is further called into question. Nelly refers to him as a ‘regular black,’ and claims he could well be a prince in disguise, fathered by the Emperor of China with an Indian queen as his mother.

If you are confused. You’re not alone.

No matter his background, Heathcliff is cleaned-up, his hair combed and styled and he is dressed in fine clothes—only to be ridiculed (again) by Hindley. Edgar Linton’s snide remark makes things worse and Heathcliff, exhibiting the impulsivity of many adolescent boys, ‘seize[s] a tureen of hot apple-sauce, the first thing [to come] under his gripe; and dash[es] it full against [Edgar’s] face and neck.’

Shocking, isn’t it? I can only imagine how painful that must have been for young Edgar. Hindley, of course, is always quick to meet violence with violence and so, he beats Heathcliff so brutally, ‘he reappear[s] red and breathless,’ proclaiming, ‘that brute of a lad has warmed me nicely.’

In modern times this is pretty appalling. The Linton children are briefly alarmed but settle in to Christmas dinner rather quickly. Catherine, however, cannot forget her beloved Heathcliff. During a visit from the Gimmerton Band she escapes to where he has been banished in the garret and eventually convinces Nelly to permit him entry into the kitchen, where the housekeeper ‘offer[s] him a quantity of good things, but he [is] sick and [can] eat little.’

At the end of this violent episode, Emily Jane Brontë provides readers with a glimpse into the future. Whilst settled on a stool next to the fire, the thirteen-year-old begins thinking about, ‘how [he] shall pay Hindley back.’

His embarrassment in front of Catherine led to a brief loss of his stoicism. Now, his patience has returned and he tells Nelly, ‘I don’t care how long I wait, if I can only do it, at last. I hope he will not die before I do!’ Nelly replies, ‘For shame, Heathcliff! It is for God to punish the wicked people; we should learn to forgive.’

What Heathcliff says next I perceive as a sort of self-soothing: ‘No, God won’t have the satisfaction that I shall. I only wish I knew the best way! Let me alone, and I’ll plan it out: while I’m thinking of that, I don’t feel pain.’

‘…you must allow me to leap over some three years…’

If you have remained with me through this long and winding essay, thank you! These first few chapters are rather meandering, aren’t they? You’ll be pleased to learn Nelly’s story is rather straight-forward from this point onward.

Were you perplexed by the exchange between Mr. Lockwood and Nelly in the last few pages of this week’s assignment’s final chapter? Their conversation is a bit convoluted and honestly, dreadfully uninteresting. Essentially, I think, Brontë included the details of their exchange to teach us a few things about our two narrators.

Lockwood is insatiably curious. He stays up and sleeps late—he is no Heathcliff.18 He is bored. Yet, with Nelly to entertain him, his attention is fixed and focused. Flattering her with his acknowledgment she is learned (for someone of her station), Lockwood is able to entice her to provide minute and personal details related to each character in her story. She promises she will not gloss over the years, but instead she will remain in his room (despite it being eleven o’clock at night), and tell him what happened during the summer of 1778, ‘that is, nearly twenty-three years ago.’ Our story continues…

What’s Next?

Now that you have your bearings, I’ll focus more closely on only a few topics in my summary (unless you really enjoy these long essays!). We’ve now been introduced to Hindley and Frances, Catherine, Heathcliff, Edgar and Isabella, Zillah, Joseph and Nelly. As well as Lockwood, Cathy and Hareton. You’ve probably formed a pretty good impression of each of their personalities; do you agree?

Next week’s assignment includes three chapters (Volume I: Chapters VIII-X). We will welcome new life, bid someone farewell and watch the Heights fall into decline. Passions will be stoked, characters will come and go.

And we’ll ramble with Catherine and Heathcliff through adolescence into adulthood.

England, Ireland and Scotland

Critics have wondered if Brontë wished for readers to imagine Heathcliff is christened after a first son—the rightful Earnshaw heir—born prior to the birth of Hindley.

She views the child’s stoic tolerance of physical abuse (e.g. stirs) as being deceitful; Nelly views Hindley as a victim, rather than the bully. And Heathcliff, she characterizes as a vindictive villain.

In Nelly’s defense, she does admit that when she nursed all three with the measles, she was partial to Heathcliff as, “he was as uncomplaining as a lamb.” Her belief is that, “hardness, not gentleness, made him give little trouble.”

Brontë provides no age for Earnshaw nor any specific malady.

North England variant of quick (lively), per Norton’s 5th edition, Wuthering Heights.

Consumption, or, tuberculosis, was the cause of death of Emily Jane Brontë’s eldest sisters, Maria and Elizabeth (1825). It claimed Emily’s brother Branwell and Emily (1848) as well as Anne Brontë (1849).

We learn this at the end of the novel, when Joseph tells young Cathy and Hareton, “Aw hed aimed tuh dee,! wheare Aw’d sarved fur sixty year” (I had aimed to die where I’ve served for sixty years.)

to memorize

The three Irish dialects are: Munster, Connacht and Ulster.

Kenrick, Donald. Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies). United States, Scarecrow Press, 2007.

In Chapter VI, Catherine refers to Heathcliff being ‘black,’ and he tells her, ‘I shall be as dirty as I please, and I like to be dirty, and I will be dirty.’ Nelly refers to Heathcliff as a ‘regular black.’ Black was used to describe any person darker than fair-skinned.

Further complicating the issues, Lockwood describes Heathcliff, “his face white as the wall,” (Ch III) and Nelly refers to Heathcliff’s cheeks as “sallow” (Ch X).

Brontë, Emily. The Annotated Wuthering Heights. Edited by Janet Gezari, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014.

or rather, a hat made of beaver, adorned with feathers

lively

Heathcliff is early-to-rise and early-to-bed. He labors; Lockwood, not so much.

When Nelly refers to Heathcliff as “it,” it broke my heart. She could have used “he,” “the boy,” “orphan,” or “bairn,” but instead chooses “it.” This single word conveys all the unspoken sentiments and sets the tone for Heathcliff’s future treatment and actions. The word choice is quite brilliant on Brontë’s part.

It is so hard to imagine what it would be like to be in Nelly's position, raised as a sibling and yet so clearly regarded as lower in status. Lockwood is condesending to her and self deceiving with his supposed wish to be isolated. I keep wondering why EB wanted to have the two narrators.