Hello! Welcome to Week Three of our Wuthering Heights read-along…

This week’s assignment is Volume I: Chapters VIII through X (8-10)

What Happens in Chapters VIII-X?

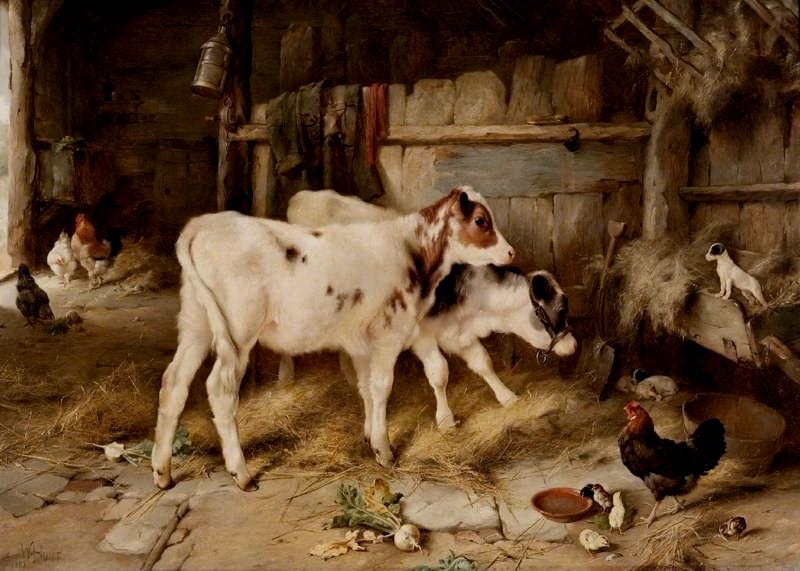

Hareton Earnshaw is born on a fine June morning. Frances, his mother, succumbs to consumption and Hindley, his father, sinks into depression and soothes himself with alcohol and violence.

Fifteen-year-old Catherine is the ‘queen of the countryside,’ and handsome, sixteen-year-old Heathcliff recoils with suspicion from ‘her girlish caresses.’ Edgar professes his love and proposes marriage. Catherine accepts, but she has her doubts…

She shares her deepest secrets with the housekeeper and Heathcliff disappears during a violent thunderstorm; only to turn up three years later: ‘a tall, athletic, well-formed man.’ He angers Edgar, delights Catherine and attracts Isabella. Ellen fears, however, ‘an evil beast prowl[s]…waiting for his time to spring and destroy.’

‘Joseph and I were the only two that would stay.’

As you’ve probably noticed by now, I am not Hindley Earnshaw’s biggest fan. I must, however, admit, I feel sorry for him every time I read Chapter VIII.

Hindley welcomes young Hareton into the world and quickly loses his wife, Frances.1 His grief is stifling, is it not? And when his tyrannical rule becomes too severe Nelly explains, only she and Joseph are willing to remain in his service at the Heights.

Joseph is ever-loyal to the Earnshaw family but Nelly explains to Lockwood that she not only stayed for young Hareton, but considers herself a foster-sister to Hindley. I think this relationship is very important—do you agree, it forms a sort of symmetry? Hindley and Nelly to Heathcliff and Catherine. Nelly admits she ‘excuses his behaviour more readily than a stranger would.’ As does Catherine, regarding Heathcliff. And, Heathcliff, regarding Catherine.

Heathcliff is loyal only to Catherine. Catherine, we see, adopts a double character.

‘And now, I’ll cry—I’ll cry myself sick!’

Emily Brontë “was personally averse to any form of medical treatment, and during her final illness she rebuffed her sisters’ attempts to send for a doctor.”2

Emily Jane had endured her mother’s death, the loss of two elder sisters, as well as the death of her beloved brother, Branwell. In Emily’s eyes, medicine proves futile. In Wuthering Heights Brontë reveals her opinion of 18th century country doctors.

This week’s assignment begins with Hindley’s wife’s death. Hinted at in the previous chapter, Frances appeared consumptive upon arriving at the Heights. Suffering from tuberculosis, caused by a bacterium called Mycobacterium tuberculosis, she was fevered, pale and suffered from lung complaints.

Shortly after the birth of Hareton, Frances Earnshaw succumbs to the disease after, ‘a fit of coughing took her.’ In Brontë’s story: Frances is unwell because she is diseased. But Catherine? Catherine Earnshaw makes herself unwell.

In late-adolescence Catherine is ‘a haughty, headstrong creature!’ Nelly even admits to Lockwood, she ‘did not like her after her infancy was past.’ The twenty-two-year-old housekeeper warms toward sixteen-year-old Heathcliff rather than her little miss; Cathy’s true nature is revealed and she is as violent as her brother Hindley.

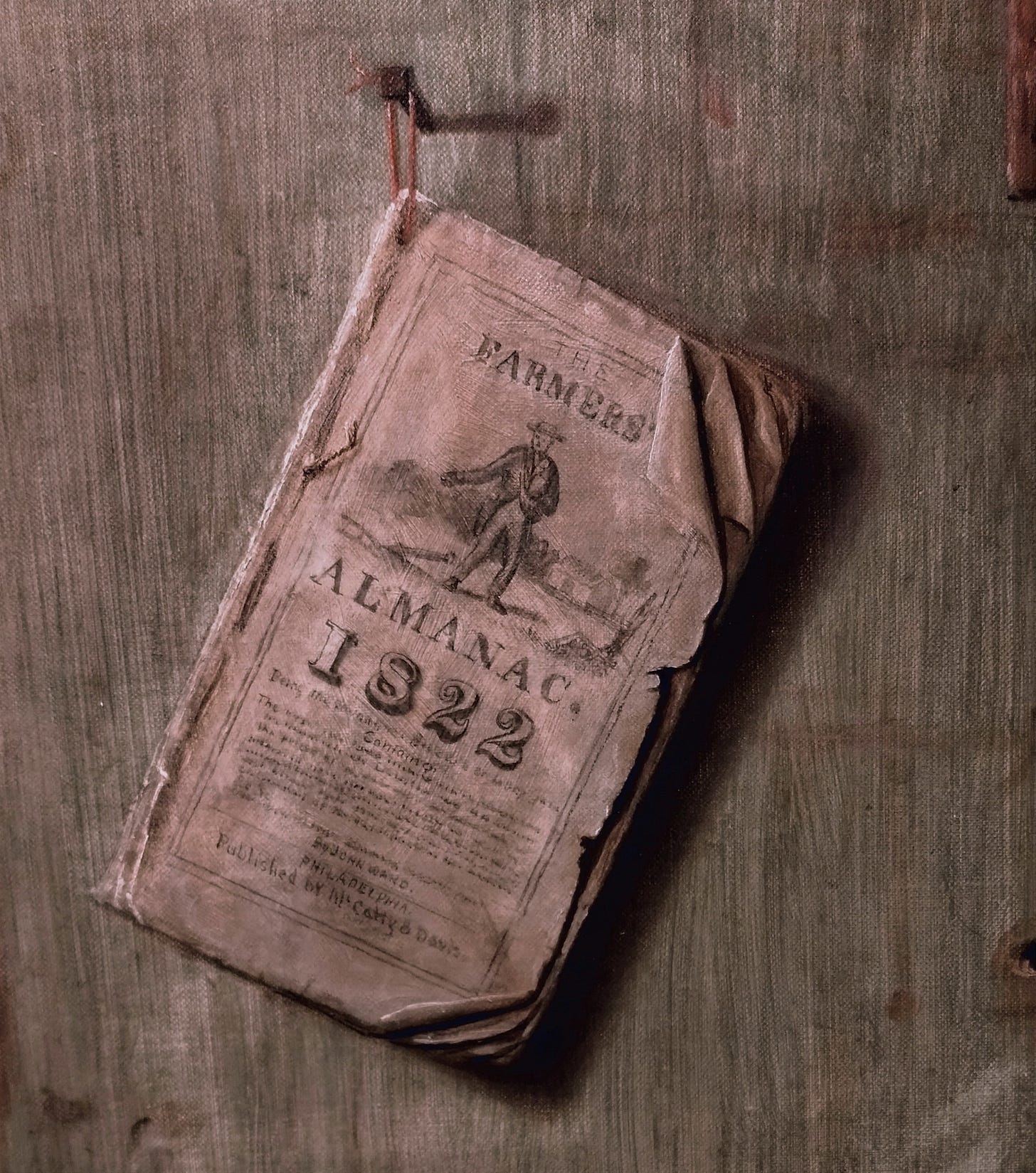

We learn this when Heathcliff—ever-yearning to spend time alone with Cathy—requests she cancel a visit with Edgar Linton. Illustrating Catherine’s increasing indifference toward him, he directs her attention to an almanack on the wall.

"What are you on the point of complaining about, Heathcliff?”

"Nothing--only look at the almanack on that wall." He pointed to a framed sheet hanging near the window, and continued--

"The crosses are for the evenings you have spent with the Lintons, the dots for those spent with me--do you see? I've marked every day."

"Yes--very foolish; as if I took notice!" replied Catherine in a peevish tone. "And where is the sense of that?"

"To show that I do take notice." said Heathcliff.

“To show that I do take notice.” Imagine adolescent Heathcliff marking the days his beloved Catherine spends with Edgar compared to those she spends with him—crosses and dots.

This is such a relatable period in adolescence, isn’t it? The mind-blowingly confusing period between childhood and young adulthood. Heathcliff is between the admiration of Mr. Earnshaw (and Catherine) in childhood and now endures seeming-indifference from Catherine, living in tyranny (at the hands of Hindley, the younger Earnshaw).

In adolescence, Heathcliff appears to relish being undesirable:

He acquired a slouching gait, and ignoble look; his naturally reserved disposition was exaggerated into an almost idiotic excess of unsociable moroseness; and he took a grim pleasure, apparently, in exciting the aversion rather than the esteem of his few acquaintance.

And, in contrast to the young boy who described Catherine’s ‘beautiful hair’ and characterized her as, ‘so immeasurably superior…to everybody on earth:’

He had ceased to express his fondness for [Catherine] in words, and recoiled with angry suspicion from her girlish caresses as if conscious there could be no gratification in lavishing such marks of affection on him.3

Ah! But when Catherine dons a silk frock for a visit from Edgar Linton, Heathcliff decides to show her he does, ‘take notice.’ Unfortunately, Catherine is now ‘full of ambition’ and recognizes Edgar Linton will offer her social advantages. Regardless, her heart belongs to Heathcliff. So, Catherine ‘adopts a double character.’

What did you think about her heated exchange with Heathcliff—telling him he is ‘no company at all?’ Heathcliff retorts, “You never told me before that I talked too little, or that you disliked my company, Cathy!” Imagining them—only fifteen and sixteen-years-old—can’t you recall those BIG feelings associated with adolescent love?

When Edgar Linton arrives—‘a beautiful fertile valley’ to Heathcliff’s ‘bleak, hilly, coal country’—one would expect Catherine to be pleased, but as Nelly explains to Lockwood, “she had failed to recover her equanimity since the little dispute with Heathcliff.” In other words, she’d yet to regain her composure.

Catherine's abuse of Nelly when the housekeeper refuses to permit an unchaperoned visit—pinching, bruising and slapping—seems a bit excessive, does it not? Her abuse of Edgar further shocks us, as domestic violence inflicted by sixteen-year-old girls, is not a common theme in Victorian literature. ‘The insulted visitor,’ briefly glimpses Catherine’s ‘genuine disposition,’ but after she threatens to ‘cry herself sick,’ and he sees the very worst of her, Edgar has a change of heart. Nelly explains, ‘the quarrel effected a closer intimacy’—and ‘the outworks of youthful timidity,’ crumble.

We now know Nelly, Joseph, Hindley, Catherine and Heathcliff are all guilty of ‘savage sullenness and ferocity.’ This is our first glimpse into Edgar Linton’s toxicity tolerance.

Tell me, did you notice this final paragraph of Chapter IX (9)?

I went to hide little Hareton, and to take the shot out of the master’s fowling piece, which he was much too fond of playing with in his insane excitement, to the hazard of the lives of any who provoked, or even attracted his notice too much…

‘He shall never know how I love him…’

I must admit, it was not until the second third time I read Wuthering Heights I took my time and slowed down. Like so many first-time readers, I rushed through the chapters, seeking the novel’s celebrated romance. The intricacy of the relationships within each of Brontë’s households—the Heights and the Grange—were initially lost on me.

Hindley is an alcoholic. So was, Emily Brontë’s brother. Stevie Davies writes:

Branwell had collapsed into alcoholism and drug addiction, dismissed by his employer and covertly rejected by his employer’s wife. He descended upon the family home in 1845 and in his mental agony and drug-derangement set about wrecking its peace, night and day.4

The short paragraph ending Chapter IX (9) prepares us for the next chapter, in which a drunken and (yes!) deranged Hindley shoves a knife between Nelly Dean’s teeth and drops his wriggling two-year-old son off a balcony.

Drunk, apathetic and depressed since the death of his wife, Hindley is despicable.

Thankfully, he is predictable. And so, the whole household behaves accordingly. Nelly stows Hareton in a cupboard when his father comes around and she is in the process of doing just that when he discovers her—and threatens, “But with the help of Satan, I shall make you swallow the carving knife, Nelly!” He alludes to having murdered the doctor, Mr. Kenneth and claims he’ll do the same to her. We see her handle this situation with a tranquility unmatched any place else in the novel.

Hindley is unhinged and his foster-sister and former playmate tolerates his behavior. Ellen Dean has been raised alongside Hindley. She cares for him and empathizes with him. I’m reminded again of Stevie Davies, discussing how Emily Brontë’s novel is a reflection of her life:

We need to realize that Branwell’s shattered personality dominated each room of the [Brontë family’s] sanctuary for the next 3 years to understand the conditions under which the sisters composed their great novels, quietly contradicting through the structural perfections of a reflective art the squalor of their immediate surroundings.

Describing the immediate surroundings of the Brontë household as squalor certainly defines the Heights. Emily’s art reflects her life. And what of poor little Hareton’s life?

Hareton—in this chapter—is rescued from certain death by Heathcliff. Wriggling to be freed from the grip of his father, Hareton plummets from a balcony, and is caught by a moody sixteen-year-old, who Nelly tells Lockwood would sooner have let the child fall than please Hindley by saving its life. Heathcliff does save Hareton’s life and we know from Chapter Two, the boy grows into a healthy man and remains in Heathcliff’s care.

Where has Catherine run off to during this episode?

According to Brontë, she’s listened to the hubbub from her room. Hindley’s taken a bottle of brandy into his care, Heathcliff has removed himself to a bench by the fire and Nelly is humming a ballad to young Hareton.

Brontë shares what Nelly tells Lockwood: ‘I was rocking Hareton on my knee, and humming a song that began’—the lines are adapted from the ballad, “The Ghaist’s Warning:”5

“It was far in the night, and the bairnies grat, The mither beneath the mools heard that," "It was late in the night, and the little ones wept, The mother in the grave heard that,"

According to Alexandra Lewis, author of the 5th critical ed. of Wuthering Heights, the ballad was translated from the Danish and included by Sir Walter Scott in a note to Canto 4 of The Lady in the Lake (1810). There has been much scholarship published in regard to Brontë’s use of the structure of the ballad throughout Wuthering Heights. If you wish to learn more, I’m including this article by Susan Stewart.6

As Nelly calms Hareton, she hears Miss Cathy whisper, “Are you alone, Nelly?” And so begins Catherine Earnshaw’s description of her love (and her social ambition) as it pertains to Heathcliff. The following scene is one of the most quoted episodes in the entire novel—from it, we acquire, ‘Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same,’ and ‘I am Heathcliff—he’s always, always in my mind, not as a pleasure, any more than I am always a pleasure to myself—but, as my own being...’

I promised this week’s summary would focus on only a few themes—and I really wish to keep my promise. Please forgive this slight diversion, as this episode between Nelly and Catherine subtly presents the myriad motivations for Catherine’s consideration of a marriage to Edgar.

Catherine likes Edgar. He is handsome, pleasant to be with, young and cheerful. And, as she says, he loves her. He will be rich, and if she marries Edgar Linton, she will be, ‘the greatest woman of the neighbourhood.’

Remember, Cathy is only fifteen-years-old in this scene. Edgar is a man of eighteen.

When asked how she loves Edgar, Catherine repeats the list of his attributes only to be legitimately questioned by Nelly, what if the young man should lose any of those attributes? As any fifteen-year-old might, Cathy wants ‘only to do with the present.’

Annoyed, Nelly accepts Catherine’s superficial notions and agrees: marry Edgar. But, Cathy remains distressed, confessing she is not entirely certain of her decision. In this scene we learn of Catherine’s heaven—a heaven not of the Christian ideal, but rather, a secular place, among the moors, at Wuthering Heights. More importantly, alongside Heathcliff. She demands that Nelly listen to a retelling of a dream she has had:

I was only going to say that heaven did not seem to be my home; and I broke my heart with weeping to come back to earth; and the angels were so angry that they flung me out, into the middle of the heath on the top of Wuthering Heights; where I woke sobbing for joy.”

Catherine believes this dream explains why in her soul and in her heart, she is convinced she is wrong to accept Edgar’s marriage proposal. She goes on:

I’ve no more business to marry Edgar Linton than I have to be in heaven; and if the wicked man in there (Hindley) had not brought Heathcliff so low, I shouldn’t have thought of it. It would degrade me to marry Heathcliff now; so he shall never know how I love him; and that, not because he’s handsome, Nelly, but because he’s more myself than I am.

Catherine views Heathcliff as the whole of herself. Hindley has brought Heathcliff so low, Catherine-as-Heathcliff must marry up, and in doing so, raise Heathcliff up, too. She is Heathcliff. And while in her soul and in her heart she feels uncertain, the union with Edgar Linton she believes benefits her, and in turn, Heathcliff.

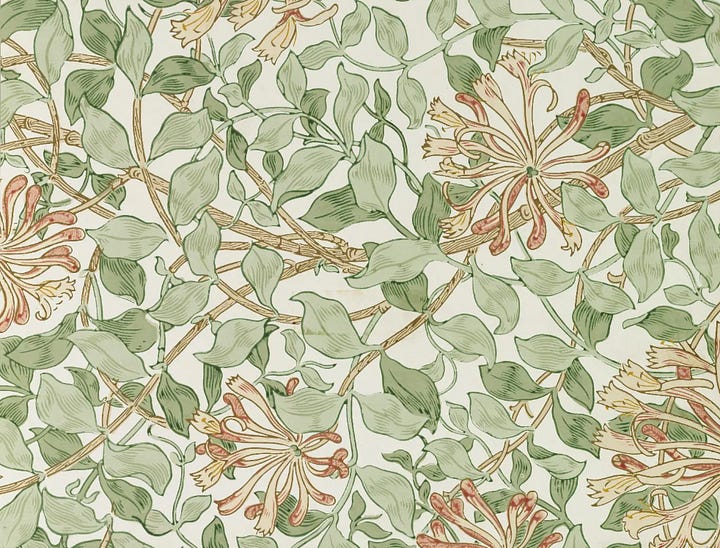

I cannot express it; but surely you and everybody have a notion that there is, or should be, an existence of yours beyond you. What were the use of my creation if I were entirely contained here? My great miseries in this world have been Heathcliff’s miseries, and I watched and felt each from the beginning; my great thought in living is himself. If all else perished, and he remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the Universe would turn into a mighty stranger. I should not seem a part of it. My love for Linton is like the foliage in the woods. Time will change it, I’m well aware, as winter changes the trees—my love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath—a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I am Heathcliff—he’s always, always in my mind—not as a pleasure, any more than I am a pleasure to myself—but, as my own being—so don’t talk of our separation again—it is impracticable…

When Emily Brontë was writing Wuthering Heights she was in her late-twenties. Isn’t her portrayal of love compelling for a young woman biographers often characterize as anti-social and reclusive? The love she expresses in this passage is part familial/part romantic. It is deep love, rooted. When lost (or destroyed), its participants are plunged into depths of grief. What did you think of the ending of Chapter IX (9)?

Heathcliff overhearing Cathy’s speech. The storm—Cathy’s persistence searching for Heathcliff. The aged Lintons’ deaths! And finally, the marriage of Edgar Linton and Catherine Earnshaw and the separation of Ellen Dean from Wuthering Heights…

He sent me a brace of grouse—the last of the season. Scoundrel!’

Oh dear! We have been propelled from a summer thunderstorm in which a nightgown-clad Catherine catches a fever wandering the moors searching for Heathcliff, into the cold winter bedroom, where Mr. Lockwood blames Heathcliff for his present illness.

So much is happening in these three paragraphs, it’s easy to become frustrated and confused, especially if one is not attuned to the natural world. Brontë moves through space and time using not only ritual and weather but even, hunting seasons, to place the reader into the ‘World of Wuthering Heights.’

Last year I wrote a short essay on the first three paragraphs of Chapter X, tap the button above to read: “The Last of the Season: Romance & Red Grouse.”

This chapter begins with yet more speculation surrounding Heathcliff—this time, the questions are posed by Lockwood:

Did he finish his education on the Continent, and come back a gentleman? or did he get a sizer’s place at college? or escape to America, and earn honours by drawing blood from his foster country? or make a fortune more promptly, on the English highways?

There is a lot to unpack here, right? Emily Brontë’s father Patrick was a sizer at St. John’s College, Cambridge in 1802—a sizer is an undergraduate receiving financial assistance for performing college duties.7 Lockwood’s reference to America is a nod to the Revolution—he believes Heathcliff may have been recruited to fight against the British (Lockwood calls England, Heathcliff’s foster country; again, characterizing him as an Other). Finally, he accuses his now-landlord of, ‘making his fortune more promptly, on the English highways.’ This refers to a ‘highwayman,’ a thief who makes his living targeting travelers.

Unable to account for details of Heathcliff’s absence, Nelly continues her story…

‘I shall think it a dream to-morrow!’

Catherine Earnshaw marries Edgar Linton. And the Lintons yield to her every whim. Both Edgar and Isabella attend to her every comfort; Nelly snidely tells Lockwood: ‘It was not the thorn bending to the honeysuckles, but the honeysuckles embracing the thorn.’

Edgar knows Catherine can certainly be thorny, doesn’t he? “The gunpowder lay as harmless as sand,” once she is married and removed to Thrushcross Grange.” No fire came near to explode it,” Nelly observes. Edgar allows nothing to agitate Catherine. And so, she is never provoked. That is, until one mellow September evening in 1783, under the cover of the Harvest Moon.

This is my tenth reading of Wuthering Heights and (in my humble opinion), this is the chapter (Chapter X) in which Emily Brontë most captivatingly portrays her setting and its inhabitants. No longer adolescents, Edgar and Isabella Linton of Thrushcross Grange are juxtaposed with Catherine Earnshaw and Heathcliff, who (day and night) once rambled the moors, ‘rude as savages.’

Oh! And my heart swoons every time I read the Nature-imagery. Heathcliff is tied so closely with the natural world, it is no wonder Brontë aligns his actions with seasons and lunar events. “On a mellow evening in September,” Nelly tells Lockwood, she is “coming from the garden with a heavy basket of apples…”

Nelly observes the moon—it is dusk, and the moon looks over the high wall of the court. It is September and as the sun sets, the moon is on the rise; this tells us the moon is full—100% illuminated. The Harvest Moon.

Heathcliff returns for Catherine. No longer the adolescent boy who impulsively ran off in a violent thunderstorm, he is a patient man of nearly twenty-years-old. He has waited an hour outside Thrushcross Grange before being discovered by Nelly, under ‘a score of glittering moons,’ reflected in the parlour window.

I’m curious: Are you surprised the notorious villain, Heathcliff, is the character who exhibits the most patience and composure? Heathcliff does not burst into the Grange and liberate Catherine; just as when they were young, he patiently observes from the outside.

Just as Brontë wishes for us to see Heathcliff’s tolerant nature, I believe, she wishes us to recognize Catherine does honestly enjoy the company of Edgar, she is certainly not intolerant of her quiet life as, ‘the greatest woman of the neighborhood.’

Nelly leaves Heathcliff in the shadows and finds Catherine in the Grange’s parlour—which ‘shows no lights from within.’ She and Edgar are sitting together (now, after dusk) gazing out an open window.

They sat together in a window whose lattice lay back against the wall, and displayed, beyond the garden trees and the wild green park, the valley of Gimmerton, with a long line of mist winding nearly to its top (for very soon after you pass the chapel, as you may have noticed, the sough that runs from the marshes joins a beck which follows the bend of the glen). Wuthering Heights rose above this silvery vapour; but our old house was invisible—it rather dips down on the other side.

This short, descriptive passage is easily missed. As readers we’re a bit anxious, aren’t we? We know what Nelly must do and we know Heathcliff is waiting outside. Ah! But this is a symbolic and evocative description of the moment just before Catherine and her beloved Heathcliff are reunited.

She is content and has accepted her role in adult, polite society. Alongside Edgar, in the posh parlour of Thrushcross Grange, Catherine gazes (from above) down onto a landscape—where she once rambled wild and free. Unbeknownst to her, Heathcliff (her lost youth) waits there in the shadows.

Gimmerton Beck runs between the Grange and the Heights, dividing the two—and the sough (or, ditch) drains from the Blackhorse Marsh into the beck (or, brook). The light from the full moon creates a silvery vapour. Wuthering Heights is obscured; youthful past—her history, which included Heathcliff—is now imperceptible.

This is when Emily Jane is at her best, isn’t it? In two sentences Brontë defines the present, reminds us of the past, and foreshadows the future. Brilliant! She quells our nervous energy by sharing a pastoral scene, and immediately redirects our attention back to Nelly and her unsettling task. I’ve always been surprised that Nelly—who is no stranger to deceit and omission—shares Heathcliff’s presence with Edgar.

Edgar remembers Heathcliff as a mere gipsy plough-boy. And when Catherine bounds into the parlour crying, “Oh, Edgar, Edgar! Oh Edgar darling! Heathcliff’s come back—he is!” her husband is not the least bit amused, is he?

Again, some of my favorite lines in the novel appear next…

Catherine wishes for her old friend and her new husband to be friends, and so she asks, “Shall I tell him to come up?” Isn’t the following exchange simply brilliant?

"Here?" he said, "into the parlour?"

"Where else?" she asked.

He looked vexed, and suggested the kitchen as a more suitable place for him. Mrs. Linton eyed him with a droll expression--half angry, half laughing at his fastidiousness.

"No," she added, after a while: "I cannot sit in the kitchen. Set two tables here, Ellen; one for your master and Miss Isabella, being gentry; the other for Heathcliff and myself, being of the lower orders. Will that please you, dear? Or must I have a fire lighted elsewhere? If so, give directions. I'll run down and secure my guest. I'm afraid the joy is too great to be real!"

Whoa! Were you uncomfortable the first time you read this exchange? I just adore Brontë’s clarity here: Catherine is Heathcliff. If Edgar wishes to segregate her old friend, banishing him to the kitchen like a common servant, Edgar must likewise banish Catherine.

Also, isn’t Brontë’s use of visual language so evocative? She used the phrase, ‘warmed me nicely,’ when Hindley gave Heathcliff a beating in last week’s assignment. In this chapter Nelly observes, after escorting Heathcliff upstairs the master and mistress’, ‘flushed cheeks betrayed signs of warm talking.’ Can we not all imagine the scene?

Inside, Heathcliff is quite literally brought to light. Now, fully revealed by the fire and candlelight, Nelly tells Lockwood (and us!):

[Heathcliff] had grown a tall, athletic, well-formed man, beside whom [Edgar] seemed quite slender and youth-like. His upright carriage suggested the idea of his having been in the army. His countenance was much older in expression and decision of feature than Mr. Linton’s; it looked intelligent, and retained no marks of former degradation.

I suppose we must accept this is Nelly’s personal opinion of him—but, I must confess, from her description it certainly sounds as though he is handsome (if you are attracted to good-postured, athletically-built, reserved gentleman who disguise their hardships). Did you notice she hints at something…untamed?

A half-civilized ferocity lurked yet in the depressed brows and eyes full of black fire, but it was subdued; and his manner was even dignified, quite divested of roughness, though too stern for grace.

I smile every time I read, “Heathcliff dropped his slight hand, and stood looking at him coolly till he chose to speak.” In a single sentence we all feel Edgar’s distress. As if the scene could not become any more uncomfortable, when Edgar feigns politeness, he is further emasculated by Heathcliff:

"Sit down, sir," [Edgar] said at length. "Mrs. Linton, recalling old times, would have me give you a cordial reception, and of course, I am gratified when anything occurs to please her."

"And I also," answered Heathcliff, "especially if it be anything in which I have a part. I shall stay an hour or two willingly!"

He took a seat opposite Catherine, who kept her gaze fixed on him as if she feared he would vanish were she to remove it. He did not raise his to her often; a quick glance now and then sufficed; but it flashed back, each time more confidently, the undisguised delight he drank from hers. They were too much absorbed in their mutual joy to suffer embarrassment. Not so Mr. Edgar; he grew pale with pure annoyance, a feeling that reached its climax when his lady rose, and stepping across the rug, seized Heathcliff's hands again, and laughed like one beside herself.

"I shall think it a dream to-morrow!" she cried, "I shall not be able to believe that I have seen, and touched, and spoken to you once more--and yet, cruel Heathcliff! you don't deserve this welcome. To be absent for three years, and never to think of me!"

Oh dear. Poor Edgar! We all feel a bit sorry for him at this point, don’t we? Remember, these individuals are young. No older than twenty-one. Neuro-biologically, each one is emotionally immature.8

What is apparent to me here is not the disrespect Catherine shows Edgar by fawning over Heathcliff, but the choice of words Brontë uses to describe the two old friends as they disengage from the society of the others altogether. Catherine is, as Brontë aptly puts it: ‘beside herself.’ Reminding us, she is Heathcliff.

Catherine and Heathcliff’s mutual delight at being reunited is mirrored in the other. Do you remember when Catherine told Nelly: Heathcliff is always, always in her mind—not as a pleasure, any more than she is always a pleasure to herself—but as her own being? They are entirely unaware their behavior is inconsiderate; as one might talk to oneself in one’s own head: they are simply sharing their most intimate feelings about how each half of the whole has struggled while parted.

I promised I will try to keep this essay short(er), so I’ll skip ahead a bit!

‘An arid wilderness of furze and whinstone.’

We learn Heathcliff has taken up residency at the Heights (rather than staying in say, Gimmerton). Heathcliff tells Catherine he wishes to be within walking distance from the Grange—Nelly believes otherwise:

I felt that God had forsaken the stray sheep there to its own wicked wanderings, and an evil beast prowled between it and the fold, waiting his time to spring and destroy.

The stray sheep is the alcoholic widower Hindley and the evil beast? Heathcliff.

Heathcliff’s continuing presence at the Grange encourages Miss Isabella’s, ‘sudden and irresistible attraction’ to him and when in a moment of jealousy the infantile eighteen-year-old confesses her desire for ‘the tolerated guest,’ the claws come out!

Isabella complains to Cathy near the end of Chapter X: “In our walk along the moor; you told me to ramble where I pleased, while you sauntered on with Mr. Heathcliff!”

Catherine is amused by Isabella’s outburst, and acts as if she can’t possibly understand why the girl is so upset about not being included in Heathcliff’s and her conversation. When Isabella accuses her sister-in-law of desiring ‘no one to be loved but [herself];’ she labels Cathy a ‘dog in the manger.’ This characterization comes from Aesop:

A Dog asleep in a manger filled with hay, was awakened by the Cattle, which came in tired and hungry from working in the field. But the Dog would not let them get near the manger, and snarled and snapped as if it were filled with the best of meat and bones, all for himself.

The Cattle looked at the Dog in disgust. "How selfish he is!" said one. "He cannot eat the hay and yet he will not let us eat it who are so hungry for it!"

Now the farmer came in. When he saw how the Dog was acting, he seized a stick and drove him out of the stable with many a blow for his selfish behavior.

Hey Catherine: Do not grudge others what you cannot enjoy yourself!

It’s true, isn’t it? Catherine may not enjoy Heathcliff, however she isn’t going to allow Isabella to have him. Isabella is right. Cathy is the dog in the manger. And she is so bent on keeping Isabella from pursuing Heathcliff, to dissuade the girl from desiring his attention, she enlists help from Nelly. Catherine persists:

Tell her what Heathcliff is—an unreclaimed creature, without refinement, without cultivation; an arid wilderness of furze and whinstone…It is deplorable ignorance of his character, child, and nothing else, which makes that dream enter your head. Pray don’t imagine that he conceals depths of benevolence and affection beneath a stern exterior! He’s not a rough diamond—a pearl-containing oyster of a rustic; he’s a fierce, pitiless, wolfish man. I never say to him, ‘Let this or that enemy alone, because it would be ungenerous or cruel to harm them;’ I say, ‘Let them alone, because I should hate them to be wronged; and he’d crush you, like a sparrow’s egg, Isabella, if he found you a troublesome charge. I know he couldn’t love a Linton; and yet he’d be quite capable of marrying your fortune and expectations. Avarice is growing with him a besetting sin. There’s my picture; and I’m his friend—so much so, that had he thought seriously to catch you, I should, perhaps, have held my tongue, and let you fall into his trap.

There is a lot going on here, isn’t there? First of all, we know Catherine would rather have married Heathcliff—in Chapter IX she admitted to Nelly, “He shall never know how I love him.” We also know Catherine considers Heathcliff more herself than she is. If Heathcliff is all of these things—an unreclaimed creature, without refinement, without cultivation, an arid wilderness of furze and whinstone—so must be, Catherine.

Furze and whinstone do perfectly represent Catherine’s depiction of Heathcliff (and to a degree, herself). Furze—or common gorse—is an evergreen shrub, the narrow leaves of which are modified into sharp spines. It is a hardy moorland plant and lives up to thirty years. Any hard, dark rocks are referred to as whinstone.

Did you notice, too, Catherine makes clear to Isabella that Heathcliff is incapable of loving ‘a Linton;’ this brief statement tells so much! If Heathcliff is only capable of marrying a Linton for fortune, perhaps Catherine—who is Heathcliff—is confessing the same?

And what was that last bit about crushing Isabella like a sparrow’s egg? Cathy wants the girl to recognize Heathcliff is completely under her control. And, he acts (or, in some cases, does not act) only if it pleases Catherine. Remember the Clare Leighton etching of Earnshaw’s death I shared last week, in which Heathcliff lies submissively across the lap of his beloved Catherine? Heathcliff may be ‘a fierce, pitiless, wolfish’ man but only because it pleases Catherine.

‘We’s hae a Crahnr’s ‘quest enah, at ahr folks.’

Oh, Joseph! If you’re having problems with Joseph’s dialect, consider reading an annotated edition of the novel—or, listening to an audiobook—it may help.

The episode leading up to the scene with Isabella, Catherine and Heathcliff in the library, in which Nelly describes her conversation meeting up with Joseph over in Gimmerton is important (but if you wish to admit you skipped over it, here is your free pass!). What Joseph tells Nelly is that Heathcliff enables Hindley’s bad behavior. At the Heights, Hindley sleeps all day, wakes up at sundown, drinks and plays cards all evening and Heathcliff encourages it. Joseph views both men as sinners—one, a gambler and alcoholic and the other, leading him down the path to destruction.

‘…remember this neighbor’s goods are mine.’

This week’s assignment ends with an episode in the Lintons’ library. It’s one of the most oft-discussed episodes in criticism of the novel—one in which Heathcliff is often portrayed as the villain. Again, I’m not convinced.

Edgar Linton has had to attend a justice-meeting and is out-of-the-house. Isabella and Catherine are still on rather prickly terms since their conversation about Heathcliff only one day prior; Heathcliff comes to call and is invited into the library by Catherine (before Isabella has time to escape). Ever-the-mean-girl, Catherine taunts her lovelorn sister-in-law. Did this strike you as odd? I am admittedly always on Team Heathcliff, yet I wonder: will no one defend Edgar? Isabella does not say, “Uh, I’m not your ‘rival,’ Catherine; you’re already married to my brother!”

There are two things I’d like to discuss in this passage:

Catherine promotes physical abuse of Isabella and provokes Heathcliff’s provocative language regarding such abuse, and;

Catherine develops a possessive attitude; claiming her yet-to-exist sons’ rights to the Linton fortune after she recognizes a union between Heathcliff and Isabella might afford him and her those benefits.

While the dialogue between the three becomes convoluted and quite frankly a bit bizarre, we learn a lot about each character’s motives and deeply held beliefs, don’t we? I’d love to hear your thoughts on these scenes…

Catherine injures Isabella, gripping her arm and forcing her to remain in the room so she may embarrass her by telling Heathcliff of her feelings for him. He is ‘thoroughly indifferent’ regarding any sentiments Isabella may ‘[cherish] concerning him.’ When Cathy insists Isabella is in love with him, he observes, “I think you belie her,” adding, “She wishes to be out of my society now, at any rate!”

Catherine continues to hold fast until Isabella digs her fingernails into Cathy’s hand. “There’s a tigress!” Cathy teases, telling Isabella she should not have revealed ‘those talons to him.’ Catherine suggests, “Can’t you fancy the conclusions he’ll draw?”

When you read this passage, how did you feel about Catherine’s behavior?

Heathcliff bumbles into this ‘cat fight’—Catherine admits, ‘we were quarreling like cats’—yet somehow by the end of the chapter Heathcliff is the one characterized as a dangerous animal. We know he could not care less for Isabella Linto; but to please Catherine, he threatens, “I’d wrench them off her fingers if they ever menaced me.” Isabella is no longer in the room to hear this threat and, he takes a moment to clarify, “But, what did you mean by teasing the creature in that manner, Cathy? You were not speaking the truth, were you?”

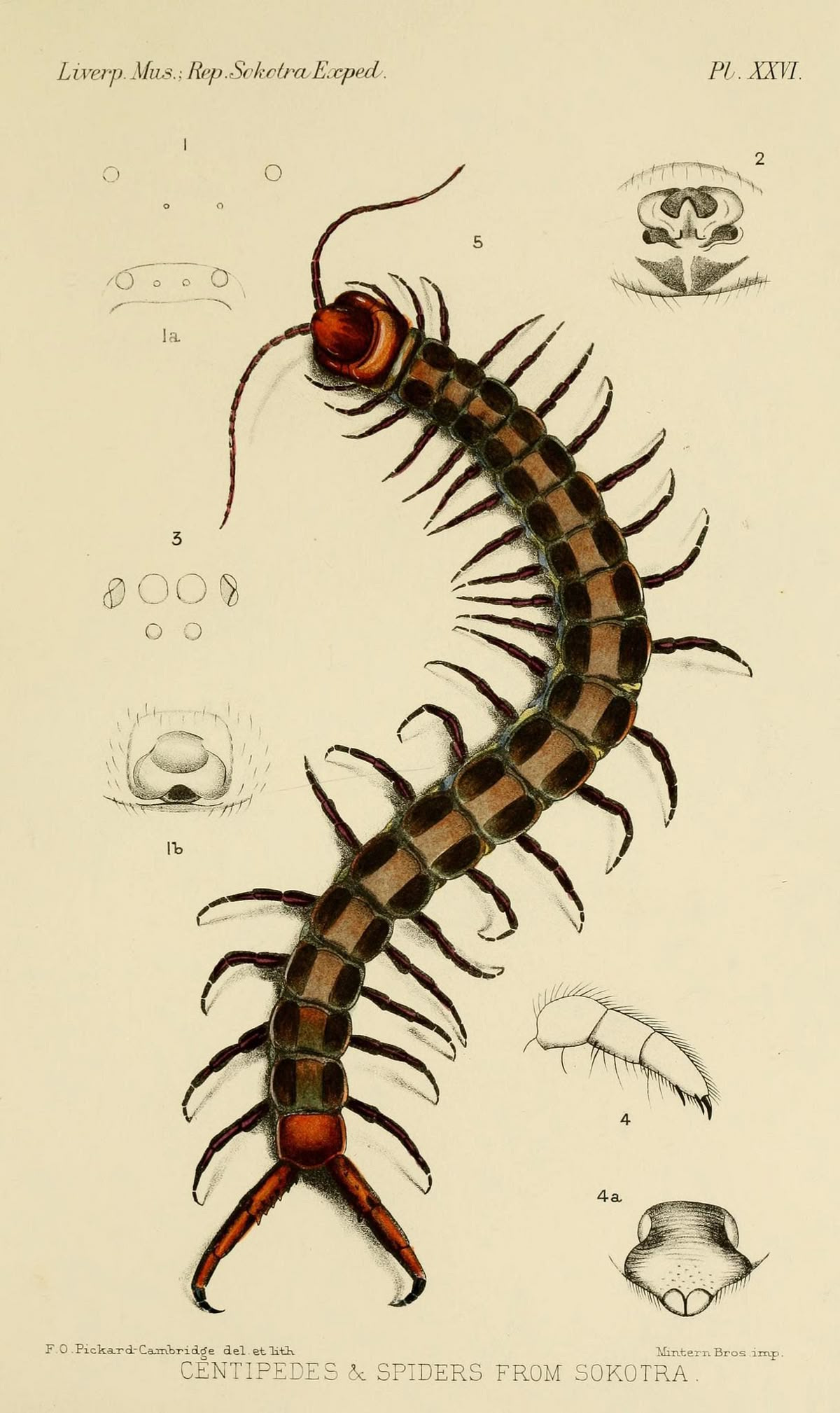

Heathcliff, who views Edgar Linton’s sister as ‘one might…a strange repulsive animal, a centipede from the Indies, for instance,’ cannot entertain the thought she might be attracted to him. He spent the majority of his adolescence repelling everyone he met (except Catherine), now women are fighting over him like cats! He is so disturbed by Isabella’s interest in him, he is now the one who is repulsed. When Cathy suggests he might ‘absolutely seize and devour [Isabella] up’, in feigned fiendishness, Heathcliff claims, “…I like her too ill to attempt it except in a very ghoulish fashion.” As if he is caught up in his need to entirely delight Catherine, he proposes physical abuse of her sister-in-law and clarifies, he will derive pleasure from regularly harming her because Isabella reminds him of her brother, Edgar:

You’d hear of odd things, if I lived alone with that mawkish, waxen face; the most ordinary would be painting on its white the colours of the rainbow, and turning the blue eyes black, every day or two; they detestably resemble Linton’s.

Shouldn’t Catherine be appalled? Heathcliff is not a bully. While he is guilty of “Edgar and the Hot Applesauce Incident of Christmas 1777,” in the story so far, Heathcliff is not physically aggressive. His single focus, his sole objective, is to regain the attention of Catherine. Since returning to the neighborhood, ‘he retain[s] a great deal of the reserve for which his boyhood was remarkable,’ yet now (when provoked to please her) he threatens to hit Catherine’s sister-in-law until she is black and blue…because Isabella’s blue eyes, ‘detestably resemble’ Edgar’s? Rather than calming him…

Catherine simply coos, “Delectably, they are dove’s eyes—angel’s!”

We know from her conversation with Nelly, Catherine quietly harbors resentment toward Isabella: ‘I’m not envious: I never feel hurt at the brightness of Isabella’s yellow hair, and the whiteness of her skin; at her dainty elegance, and the fondness all the family exhibit for her.’

As his twin—‘I am Heathcliff’—Catherine feels Heathcliff’s envy of Edgar and so she uses it, taunting him: The Lintons’ blue eyes are delectable, not detestable. When she recognizes he has designs to pursue Isabella as, ‘her brother’s heir,’ Catherine warns: ‘Half-a-dozen nephews will erase her title, please Heaven!’ Here again, this is such a short exchange (tucked in at the end of the chapter), but it is so important. Catherine is warning off Heathcliff—warning him against pursuing marriage with Isabella. She is not doing this because she wants handsome Heathcliff for herself, but instead, she wants ‘this neighbour’s goods.’ She evokes a fruitful future, in which with Edgar, she will produce multiple (six!) sons to secure the Linton fortune for herself. Herself. Did you notice: Heathcliff replies, “If they were mine, they would be none the less.”

What goods are Heathcliff’s are Catherine’s, but is Catherine as selfless?

This week’s assignment ends with Heathcliff smiling, ‘with ominous musing,’ and Catherine believing she has thwarted any thought of him pursuing Isabella. I’m so curious to hear your thoughts on the matter…

What’s Next?

Next week’s assignment includes four chapters (Volume I: Chapters XI-XIV).

We will meet an elf-locked, brown-eyed boy, Isabella will receive a kiss, there will be a quarrel, an elopement, an estrangement and a reunion.

Frances Earnshaw dies of consumption/tuberculosis.

Caldwell, Janis McLarren. “Wuthering Heights and Domestic Medicine: The Child’s Body and the Book.” Literature and Medicine in Nineteenth-Century Britain: From Mary Shelley to George Eliot (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004), pp. 68-74, 78-96.

Brontë wants readers to know: Heathcliff is aware of his social status in early-adolescence.

Davies, Stevie. Emily Brontë: the Artist as a Free Woman. Carcanet, 1983.

A dead mother returns to her children from her grave because they are mistreated and crying. This is another reference to Frances, who Nelly conjured earlier in the scene.

JSTOR permits 100 free articles per month with registration.

Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights: A Norton Critical Edition (Fifth Edition). Edited by Alexandra Lewis, 5th ed., W. W. Norton & Company, 2019.

Emotional decision-making and cognitive control is not fully mature until approximately age 32, according to Martha Denckla, director of developmental cognitive neurology at the Kennedy Krieger Institute at Johns Hopkins University.

I'm so glad I'm doing this Read-Along. As a first time reader I'm definitely devouring quickly and therefore missing things. Thank you!

I like your point about the domestic violence. Emily was perhaps writing about what people were experiencing. I am always surprised when I find out how many women have experienced beatings and other forms of violence.