“Wuthering” being a significant provincial adjective, descriptive of the atmospheric tumult to which its station is exposed in stormy weather.

Volume I: Chapter I

When I pulled my tiny, pocket edition of Wuthering Heights1 down off my bookshelf earlier this summer I had not expected to become entirely obsessed with its author and her story. Alas, I am.

During my first reading I was slogging through the text. I was grappling with the dual narration, struggling to keep all of the characters’ names straight in my mind and of course, there is Joseph’s dialect! I put The Annotated Wuthering Heights on my wish list and my husband lovingly purchased it for me for my birthday. It was a game-changer. Reading Wuthering Heights a second time—aided by illustrative marginalia organized by Janet Gezari, Lucretia L. Allyn Professor of Literatures in English at Connecticut College—helped me to understand the structure of the story.

When reading the novel the first time I didn’t immediately understand that Lockwood is an important sort of narrator. He is a ‘cultural tourist,’ a “well-to-do Englishman…setting out from London in search of ‘picturesque countryside and sublime highland landscapes.’”2 I’m reminded of the folks who come to this area—the Ridge and Valley region of the Appalachians—to ramble through our state parks and curiously gawk at the anabaptist Amish.

Nelly Dean annoys me. Lockwood amuses me. His narration begins:

1801—I have just returned from a visit to my landlord—the solitary neighbour that I shall be troubled with. This is certainly a beautiful country! In all England, I do not believe I could have fixed on a situation so completely removed from the stir of society. A perfect misanthropist’s heaven—and Mr. Heathcliff and I are such a suitable pair to divide the desolation between us. A capital fellow! He little imagined how my heart warmed towards him when I beheld his black eyes withdraw so suspiciously under their brows, as I rode up, and when his fingers sheltered themselves, with a jealous resolution, still further in his waistcoat as I announced my name.

Volume I: Chapter I

After his initial meeting with Heathcliff the city-dweller believes they are kindred spirits. Sure, Heathcliff seems, “more exaggeratedly reserved,” than Lockwood, but the tourist’s curious desire to immerse himself in the region attracts him to the surly man who utters, “Walk in!” through closed teeth.

Every summer thousands of tourists inhale the pungent odor of fresh manure to catch a glimpse of horses turning soil here in, “Amish county.” Brontë’s Lockwood is willing to endure still worse: he will be mauled by half-a-dozen of Heathcliff’s dogs.

Guests are so exceedingly rare in this house that I and my dogs, I am willing to own, hardly know how to receive them.

Volume I: Chapter I

Atmospheric Tumult

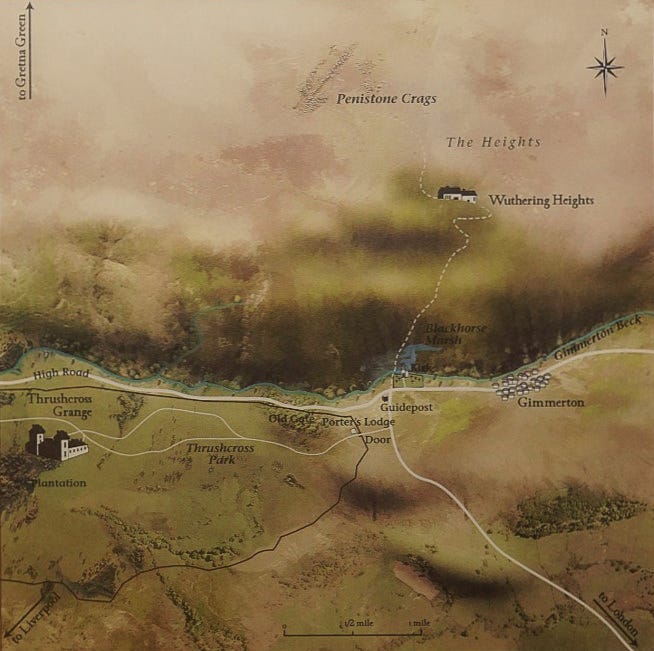

What Emily Brontë so completely accomplishes in this first chapter of her novel is to introduce to the reader, the whole of Wuthering Heights—the setting, the residence, its furnishings and its inhabitants. And we immediately recognize: it is certainly not Thrushcross Grange.

Brontë was fond of the west wind, which blew across the moors from Lancashire; she was always looking out of windows; and in the evenings after dinner, Emily carried a little ‘buffet,’ or, stool, with her on her walk on the moors. 3

Ever observant, it is no wonder she could so vividly illustrate for readers, the exterior and interior of The Heights. Within the first few sentences we learn Lockwood is in a beautiful region of England, “completely removed from the stir of society.” And who is the first inhabitant we should meet? Heathcliff. Reserved and suspicious, he refuses to offer his hand to Lockwood when the stranger introduces himself and instead keeps, “his fingers sheltered,” sinking them, “still further in his waistcoat.”

Like Lockwood, we are immediately interested in a man so, “exaggeratedly reserved.”

Brontë makes clear: Heathcliff assesses Lockwood from behind his closed and bolted gate. Though he is dressed as a gentleman, Heathcliff behaves like (as Lockwood will eventually describe him) a, “homely, northern farmer, with a stubborn countenance.” He has not willingly welcomed his tenant onto the grounds of Wuthering Heights, acquiescing only after Lockwood’s horse pushes against the barrier; the gate is unchained and sullenly, Heathcliff permits Lockwood entry.

By the time we finish reading the first page or so, we sense disorder and agitation within—and as we (and Lockwood) pass over the overgrown flags, Brontë utilizes Joseph to further alienate us from the comforts provided in the city or, a country manor. The old man is both hostler and manservant; “the whole establishment of domestics,” Lockwood observes.

Once our narrator is in the position to behold the dwelling, Brontë imparts her skills of observation. Lockwood’s description of the landscape provides readers with ample opportunity to imagine the setting in which Catherine Earnshaw was born and raised—and to which, the young Heathcliff was relocated, bullied by Hindley Earnshaw and finally, through careful, calculated manipulation, he now owns.

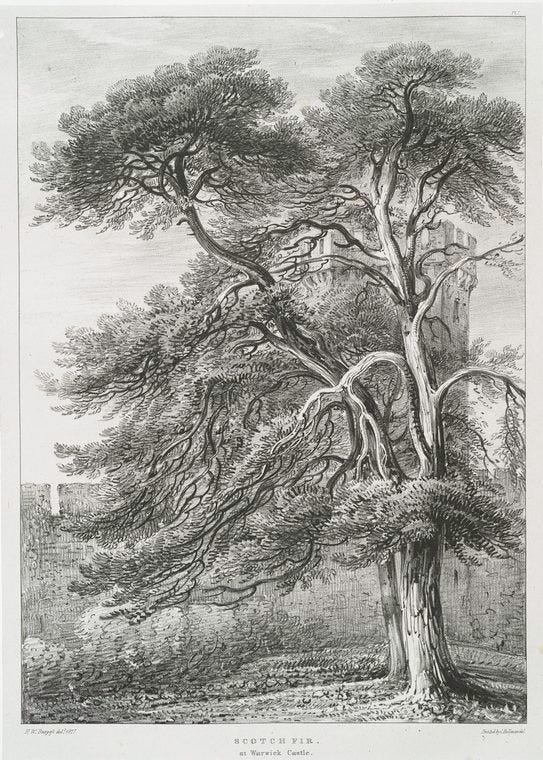

Pure, bracing ventilation they must have up there, at all times, indeed: one may guess the power of the north wind, blowing over the edge, by the excessive slant of a few stunted firs at the end of the house; and by a range of gaunt thorns all stretching their limbs one way, as if craving alms of the sun.

Volume I: Chapter I

I am curious to know if Lockwood accurately identified the fir trees —and if so, what sort of fir—as fir trees are not native to the United Kingdom. Could it instead be Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris) he observed, a common name of which is, Scotch Fir?

Scots pine are planted in Haworth and so, Brontë was likely referring to Pinus when she wrote of firs. The ‘gaunt thorns’ to which Lockwood refers are hawthorn trees (Crataegus). And, about those thorns. Brontë describes them as, “all stretching their limbs one way, as if craving alms of the sun.” Is that not a beautiful observation?

Craving Alms of the Sun

I read Wuthering Heights five times before I really stopped to visualize the image of a tree stretching its limbs ‘as if craving alms of the sun.’ Hindley, Catherine, Heathcliff, Hareton and Cathy—the inmates of Wuthering Heights—suffer individual heartaches; the line resonates with (re)readers especially because, we know this and after all…

Doesn’t everybody crave warmth and security?

How profound is that short little statement? Admittedly, it isn’t immediately profound but after a close reading of that single paragraph, I’m entirely committed to (re)reading each of Brontë’s myriad descriptions of the natural world—as this is the first time I’ve glimpsed human traits assigned to Nature, rather than traits of Nature assigned to the humans.

It is at this point our narrator Lockwood inspects the penetralium. Thankfully, my Norton Critical Edition defines penetralium for me; it refers simply to the innermost part of the building. And it is in this innermost part we meet the dogs who will maul the intruder. We also meet Zillah, the “lusty dame, with tucked-up gown, bare arms, and fire-flushed cheeks,” who serves as Heathcliff’s housekeeper.

Zillah means ‘shadow,’ she is one of two wives of Lamech in the Holy Bible

Zillah, in the shadows, and sharing with Nelly Dean all the goings-on at Wuthering Heights is well-named, don’t you think? One of two housekeepers, keeps a wary eye on one of two houses.

In this first chapter of ‘the most haunting and tormented love story ever written,’4 Brontë (through Lockwood) places readers into Heathcliff’s house, assessing his collection of oatcakes and mutton. Wait. What?

First-time readers expect a supernatural romance, not pewter tankards. And yet, it is these details in the first few pages which aid in our visualization of the space.

I observed no signs of roasting, boiling, or baking about the huge fire-place; nor any glitter of copper saucepans and tin cullenders on the walls. One end, indeed, reflected splendidly both light and heat from ranks of immense pewter dishes, interspersed with silver jugs and tankards, towering row after row, in a vast oak dresser, to the very roof. The latter had never been underdrawn: its entire anatomy lay bare to an inquiring eye, except where a frame of wood laden with oatcakes, and clusters of legs of beef, mutton, and ham, concealed it.

Volume I: Chapter I

Readers envisioning Heathcliff’s space are made aware of his wealth and prosperity. An abundant collection of pewter dishes, jugs, tankards and varying meats impress Lockwood. Will the first-time reader recognize this is Brontë displaying Heathcliff’s station? Admittedly, I did not. These domestic details held little interest for me. Only on my third reading did I wonder, what is an oatcake?

Above the chimney were sundry villainous old guns, and a couple of horse-pistols, and, by way of ornament, three gaudily-painted canisters disposed along its ledge. The floor was of smooth white stone; the chairs, high-backed, primitive structures, painted green, one or two heavy black ones, lurking in the shade. In an arch under the dresser, reposed a huge, liver-coloured bitch pointer surrounded by a swarm of squealing puppies, and other dogs haunted other recesses.

Volume I: Chapter I

As Much a Gentleman as Any Country Squire

Chapter One, if anything, provides us with our first physical description of Heathcliff:

The apartment and furniture would have been nothing extraordinary as belonging to a homely, northern farmer, with a stubborn countenance, and stalwart limbs set out to advantage in knee-britches and gaiters. Such an individual, seated in his arm-chair, his mug of ale frothing on the round table before him, is to be seen in any circuit of five or six miles among these hills, if you go at the right time, after dinner. But Mr. Heathcliff forms a singular contrast to his abode and style of living. He is a dark-skinned gypsy in aspect, in dress and manners, a gentleman, that is, as much a gentleman as any country squire: rather slovenly, perhaps, yet not looking amiss with his negligence, because he has an erect and handsome figure—and rather morose.

Volume I: Chapter I

Much has been written about Heathcliff’s racial identity. He is described as, “a dark-skinned gypsy,” “dark almost as if [he] came from the devil,” “it,” and by his own future wife, “like the son of the fortune-teller.” His future father-in-law, upon laying eyes on him in adolescence, remarks :

Oho! I declare he is that strange acquisition my late neighbour made in his journey to Liverpool—a little Lascar, or an American or Spanish castaway.

Volume I: Chapter VII

I will certainly write more about the topic of Heathcliff’s identity in a future essay, but for now, I will say, my personal belief is that Emily Brontë had the victims of the Irish famine in mind when she created Heathcliff—her brother Branwell had experienced seeing them in Liverpool in August of 1845. Brontë’s description of Linton Heathcliff later in the novel provides no details which make me believe he is fathered by anyone other than a Caucasian—and so (for now), I am in the ‘Heathcliff is Irish’ camp.5

Truth-be-told, I was perplexed when I initially read Wuthering Heights. Firearms hung above a mantle, pewter tankards, and unruly dogs—Chapter One felt not unlike a visit to my paternal grandparents’ farmhouse in the 1970s. In other words, it was lacking in romance.

But what Brontë does in this chapter is provide us a glimpse into the future (to keep in mind as we ramble through the past). Heathcliff owns both Thrushcross Grange and Wuthering Heights, and he is wealthy and well-spoken, yet unsociable and surly. Like Lockwood, we want to understand him and so, we continue reading…

I really do hope you enjoyed reading this essay. When I have a spare moment I gather my colored pencils, my copper page points and tabs and I spend time engaging in a close reading of a paragraph or chapter. This essay is the result of such an exercise!

A Bit of Housekeeping

This Substack publication is brand-new and so, I’ve been working out some of the kinks. This is the sort of post I hope to share more often; one filled with links and resources which will support readers and (re)readers of Wuthering Heights.

If you know someone who might enjoy reading Symbolism & Structure, please Share the publication (or this essay). And, if you feel so inclined, Like, Comment or Restack!

Also…please let me know if something is not working. Are there too many images? Too few images? Links broken or buttons causing distractions? I plan to open the Chat feature eventually and I’m still figuring out how to add a Message-me option.

Thank you for your patience…moreso, thank you for your support & encouragement!

Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. Gramercy Books, 1847 (2006).

Brontë, Emily, and Charlotte Brontë. The Annotated Wuthering Heights. Edited by Janet Gezari, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014. [archive.org]

Chitham, Edward. A Life of Emily Bronte. Amberley, 2010.

Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. 1st Vintage Classics ed, Vintage Books, 2009.

Rather than being a fair-eyed, fair-haired, ivory-skinned ‘petted thing,’ Heathcliff (as a child, adolescent and adult) is unkempt, dark-eyed, and dark-haired. His complexion is likely that of someone who spends copious amounts of time in the out-of-doors.

Image Credit: High Withens, Haworth Moor, 20th c, Mary l’Anson | Brontë Parsonage Gallery

Excellent post!

This is making me want to read the book again. Thanks!